The Vanished Publisher V

Tobias Meinecke & Eric Darton

To read the previous installments, see issues 4, 5, 6, & 7 or follow the links at the bottom of this page.

Café des Westens, Berlin. Collectively known as Café Größenwahn (Visions of Grandeur), a handful of important Kaffeehäuser in Berlin, Munich and Vienna served as the gravitational centers for bohemian, intellectual and artistic life from the mid-19th century until the advent of the Nazi era. It is reasonable to assume that the Café des Westens, situated on the glamorous Kurfürstendamm boulevard – not far from Klemm’s Verlagsanstalt in Grunewald – was one of the watering holes he frequented to meet with artists, authors and collaborators.

Caveat lector: Everything of note that happened in the life of Hermann Klemm, and is of historical record, is in this book. But not everything you read in this book happened or is of historical record.

Berlin, 2025

If your last memory of me, good Reader, is of a man protesting, indeed battling, against his resurrection by that pair of prodders and pokers – my descendants! – I have to confess that I have lately begun warming to the experience. No, that does not do justice to the feeling, for I now find myself actively relishing the rediscovery of my life through their sincere, though let us say at times imaginative, efforts. All else aside, they’re turning me into an entertaining story – one I might even consider publishing – if I could see a decent profit in it.

Indeed were such things possible, I would thank them for, however unwittingly, offering me the opportunity to view my life as though it were a spectacle unspooling on the silver screen at the Zoo Palast. I understand now, why those ever-shifting images always held my Alma their thrall. And yes, it pleases me to see the substance of my life – or at any rate its literary adaptation – offered freely to the world.

Would you like to hear something even more fantastical? As I read along with you, I find my horizon expanding beyond those forty-four years of my temporal existence. Through these pages, I now see Alma in maturity, even growing old. And I am surprised at how it tugs my heart strings to witness her slowing down, living for as long as she was able to in our villa in Grunewald, struggling through the post-war years, shorn of the comforts I was able to provide in our boom times. My Alma: never lamenting, never complaining.

Hilde and Ilse, too, make their appearances – no longer the headstrong teenagers they were when I bid them farewell, but having blossomed into self-confident, opinionated, adult women with husbands and children of their own. And oh, seeing those little ones, Benno, Reni, Karin, my namesake Hermann, and Jörg. What a joy it would have been to pluck them from their prams, toss them high and catch them, laughing delightedly. And a few years later – a mere blink of the eye – off they go on their wooden horses, like a troop of proper cavalry!

The Wedding of Hilde Klemm and Carl-Ludwig Wedekind took place six years after Hermann’s death. Also present are Alma, daughter Ilse (with her recently-wed husband Alex Weidemann), Hourch and his wife.

But even as my view expands the tableau changes, transforms. At the edge of the horizon an impenetrable tar-like darkness hovers; a dreadful creeping substance grabs hold of things and pulls them under. It engulfs the Verlagsanstalt – my life’s work – and the source of the fortune I had hoped to bequeath my dear ones. Without my hand to guide it, the enterprise languishes until the second war – who could have imagined it would come so soon? – delivers the final blow. Ah, the vanishing of my hoped-for House of Klemm – this pains me far more than the memory of the bodily injuries I sustained at the front.

There are other things, too, which I would have preferred not to see – the formost being the inscription on my beloved’s headstone: Alma Klemm-Dietrich! At least the body of that dandified grifter is not mooching on our plot. Whoever saw to it that he was buried elsewhere – you have my eternal thanks! And if it were not sufficiently disheartening that my son-in-law Alex, with whom Ilse was completely smitten, made a total hash of running the Verlagsanstalt, I had to look on helplessly when he abandoned her and vanished into the Far East and Central America – bent on who knows what unsavory schemes. I swear if I had been alive, I‘d have fetched my Parabellum Luger P08 from the attic, cleaned and loaded it, then tracked the scoundrel down and brought him back at gun point. Still, my girls knew that their Papa loved them, and the tears they shed around my grave would have melted hearts of stone.

Although Klemm advertised his Verlagsanstalt as being headquartered in the mansion enclave of Berlin-Grunewald, the building itself – on Caspar-Theys-Straße – sits right on the border of the adjoining neighborhood of Berlin-Schmargendorf, in whose cemetery the family plot is located.

But back to happier associations. Is it not everyone’s hope to be eulogized by their best friend, and so movingly that all hearts are filled with grief and one’s departure? As you already know, good Reader, it was Hourch who performed that heartfelt task. And now, thanks to those pokers and prodders, I have able read his words, and imagine him speaking them aloud. Ah, how they recalled me to those early enterprising days in Rastatt, Freiburg and Stuttgart, when we were so replete with life – overflowing in equal measure with grand ideas and foolish pranks. By God, we lived it up! How convinced we were that a spectacular destiny awaited us. All hail the young adventurers – of then, and now!

Yes, old Hourch did his mentor proud, but if you had asked me back in, say ‘02, who would be the one to deliver my eulogy, my chips would have been on Beckmann. It was he, after all, who matched my drive, my optimism, and at least early on, my risk-taking. Who but he unfailingly backed my most ambitious visions? Or proved more adept at putting the locomotive back on track when I derailed it? It was Beckmann who made things right with Heinrich Beer, our first big investor and the man I called Papa before Alma and I were even engaged. The truth is I had nearly alienated his belief in my capabilities. Disaster loomed, but Beckmann came to the rescue and, over Bienenstich and coffee, reeled the sceptic back in. I overheard Papa Beer saying to Beckmann once “Hermann needs you more than he can know. You are the one who makes people trust what he promises.“

It is often said of the dead that their struggle is over. That nobody can hurt them anymore. Perhaps that is true, but when one is pulled back from Nothingness into whatever state this is, one may feel things as intensely when one was alive. Which is why it saddens me so that Beckmann was absent from my funeral – though I can hardly bring myself to blame him. After all, our partnership had ended fourteen years before, in 1908, amidst shouts and mutual insults, even threats to kill one another! But are words spoken in the heat of the moment sufficient to sever all prior bonds and erase all memories of past, shared glories?

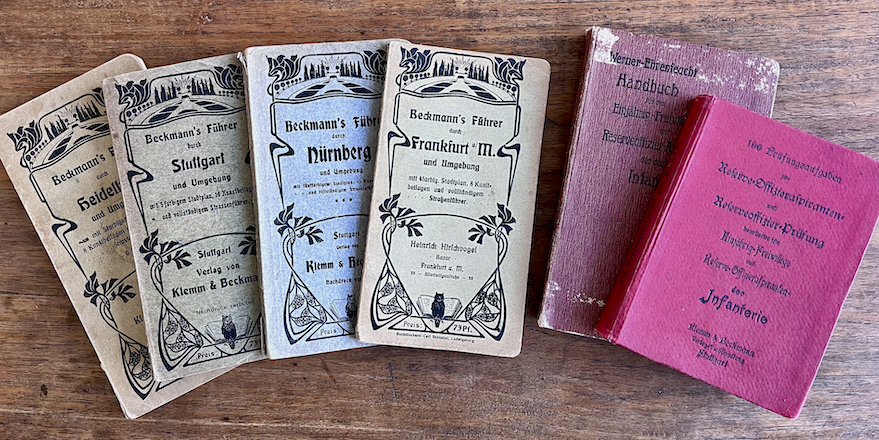

In hindsight our parting of the ways seems inevitable. What nearly bankrupted us, and, as I see it now, precipitated the split, was what I call the French Fiasco. I’ll admit it was a grave miscalculation on my part. Albeit one which I could not forsee. My instinct told me that the time was ripe to issue a grand history of the War of 1871. Think again, Herr Klemm! What I entirely underestimated was the degree to which my countrymen hated the French – to the point of not wanting to know anything about them. Well, Beckmann and Klemm survived that debacle by the skin or our teeth, but it drove a wedge into our partnership. For my part, I remained as ready as ever to seize exciting opportunities, but the experience made Beckmann turn wary in the extreme. One couldn’t reason with him – he flat-out demanded that we confine ourselves exclusively to Nützliches und Anwendbares, useful and reliable staples of the trade: Cookbooks, almanacs, travel guides, military handbooks – in short, the bread-and-butter projects that had permitted us to make a gamble now and again. I thought differently, and still do. Those sorts of books didn’t need us. They could and would be published by a score of other presses. Certainly I believed in making money – but not to the exclusion of seizing opportunities – even as they presented themselves. And if not, why I’d create them!

Inevitably, though, a painful awareness was brought home to me. For all his untiring drive, for all the mountains he‘d climbed and distances covered hawking the wares ofBeckmann & Klemm, and for all the fervor he put into our move from Stuttgart to Berlin, my partner would never convince himself to aim for the stars again. Summa summarum, Beckman had, far more than I, internalized the lessons of our first boss and mentor in Freiburg, Paul Lorenz. I can still hear Lorenz‘s voice today when he overhear us rhapsodizing over lunch about the vast, untapped potentials of the marketplace. “Boys,“ he said, “this is no glorified trade, nor holy calling. What we do is take stacks of printed paper, paper that may or may not contain worthwhile information, titilation or distraction, and slap a cover around it – ideally one that pops the eye open ahead of the pocketbook. Before which we’ve calculated, exactly to the pfennig, the highest price the buyer will pay. That’s it, no more, no less. Welcome to the book trade, boys!”

A sampling of the ”useful” books published by Beckmann & Klemm: travel guides, handbooks, cookbooks, and train schedules – favored by Beckmann for their reliable sales, but distained by Klemm.

*

Frankfurt / Main, 2025

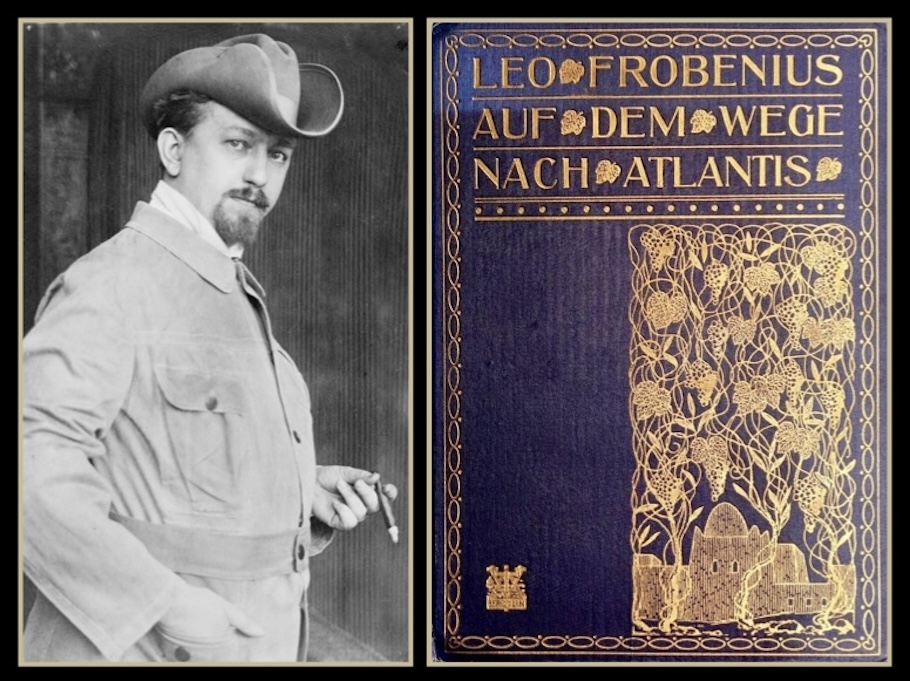

Considered one of the founders of the field of Cultural Anthropology (Ethnology) Leo Frobenius (1873-1938) gained fame when he published the findings of his second African Expedition (1907-1909) under the title Der Weg nach Atlantis (The Road to Atlantis). The book, combining scholarly research with exhuberant speculation, was one that Hermann Klemm almost certainly knew about and would likely have admired.

Klemm? Klemm? I beg your pardon? Who is this Persönlichkeit you are inquiring about? Who? Klemm der Verleger? Publisher of what? Oh, that book! The Big Book. Of course I remember it. But let me advise you, young man, you who are asking questions about this Klemm – this is foolish pursuit. You might as well try to hold water with a seive. Now I, Leo Frobenius, have published numerous books over many, many years. Important books, without which our culture, your culture should you ever wish to venture into it, would be the poorer. And yes, all of my books had publishers, but who remembers them? So I ask you, why would you dedicate even the slightest portion of your life’s energy to writing about a publisher? Unless you are an immortal, or a God, and thus have all the time in the universe on your hands. Then go ahead, write about publishers to your heart’s content.

No, I did not think you are immortal. Unlike me. But this is not your fault. How many can be Leo Frobenius? Have you devoted your lifetime to ground-breaking research? To how many classic scientific works have you served as both father and mother? Do you lend your name to a world-renowned and still-extant Institute? Were researchers, professors, intellectuals by the score doing your bidding, flocking to your lectures, following in your footsteps? Of course not. So to me your efforts are of no more consequence than that publisher you’re inquiring about, Klemm. What did he achieve of lasting value? In what way did he contribute to the sum of human knowledge? See, you are speechless because your Klemm is as irrelevant to the big picture as the old man who patched my bootsoles in Cape Town, or those fellows who outfitted our vehicles in Botswana, sewed our tents in Addis Ababa, and saddled our camels in the Sudan. Mere functions encased in human bodies. Entirely interchangable men, of no consequence. Why even learn their names?

You smile when I say big picture. As if you could know what I’m talking about. Still, I’m glad you seem curious. To begin with, the big picture has a name – one which I invented. Cultural Morphology. Remember that, if you can. I’m aware that the term has fallen out of favor in your times. Still, whatever the Institute may call itself now, it is devoted to the discipline which I was the first to identify and give a name. And which entails the exacting, painstaking work of research, collection and systematic documentation. Prove, publish, champion: there are my watchwords. Who else but Frobenius spent a lifetime exploring the essences of a humanity as yet unknown? Oh it sounds like a glamorous adventure, but the heart and soul of it is field work. Dusty science, dangerous science, thrilling science. If you haven’t answered its call, you are missing out, young man.

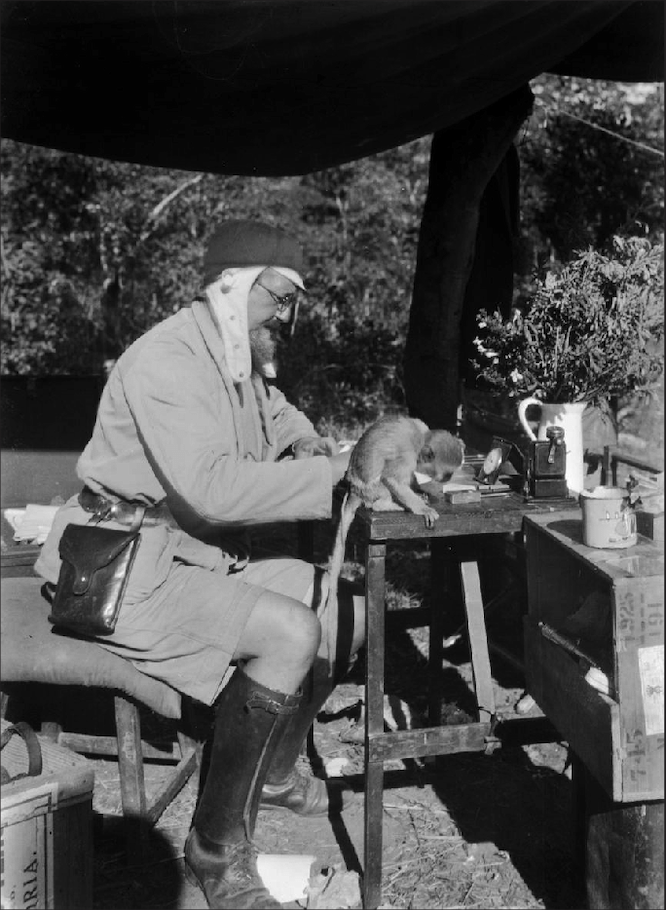

Frobenius in 1923 in Zimbabwe, then known as Rhodesia. His fieldwork included numerous meticulous drawings of fragile prehistoric rock art.

That smile again. If I didn’t know better, I’d say it was a smirk. So… inventing an entire branch of knowledge from scratch does not impress you? Without it, how would we know where we come from? How could we trace the lines by which we are all connected, going back to Adam and Eve? I refer to the first actual humans, not that simpleton pair from the Bible.

Yes, Hermann Klemm… I can vaguely recall what he looked like. But are you sure you wouldn’t you rather hear about a man who was worth remembering? I speak of his Majesty. Which Majesty? O tempore, o mores. The Kaiser, of course, Wilhelm II. You may wish to enlighten your readers to the fact that the Emperor took a keen interest in my work. In addition to his material support, he continuously inquired about my discoveries, and delighted in hearing reports of my far-flung travels. So great were his enthusiasms in this regard that I came to suspect, had he not been burdened with the duties of König and Kaiser, that Wilhelm would have wished to assist me at my side. Though for all that, deep thinking and logic were hardly innate to him. So it fell to Frobenius to instill in his Majesty such scientific method as he could grasp – a task both frustrating and paradoxical. Imagine having the duty of educating the man who, apart from commanding the Fatherland, also rules your pocketbook.

Ah, but if you would still rather hear about your Ur-Opa, I will humor you as best I can. Now when did I first hear of Klemm? It might have been before or during the War, perhaps from Ferdinand Freiherr von Reitzenstein, a colleague of dubious capabilities and questionable predelictions. His untiring scientific inquiry into the nature of sex stood – at least to my mind – in stark contrast to his entire lack of worldliness. The fellow might as well have been a virgin! Indeed he displayed a näiveté that in a child or woman would have been nearly adorable. Then again, it may have been von Reitzenstein‘s side-kick, Albert Friedenthal, who introduced me to Klemm. Albert‘s piano playing was better by far than his scholarship – I thought of him more as a hobbyist than an ethnologist. Of course neither of the pair ever engaged in serious field work – they found it quite beneath them – and hardly ventured out of their offices except in search of juvenile amusements or to woo prospective benefactors.

Now you see, young man, this inquiry of yours has put me in a terrible mood. In fact you’ve succeeded in stirring up a host of resentments I had nearly buried, though they are all entirely legitimate. It makes my blood boil to think of all the funding these two fools received for their flimsy, sensationalist “studies.“

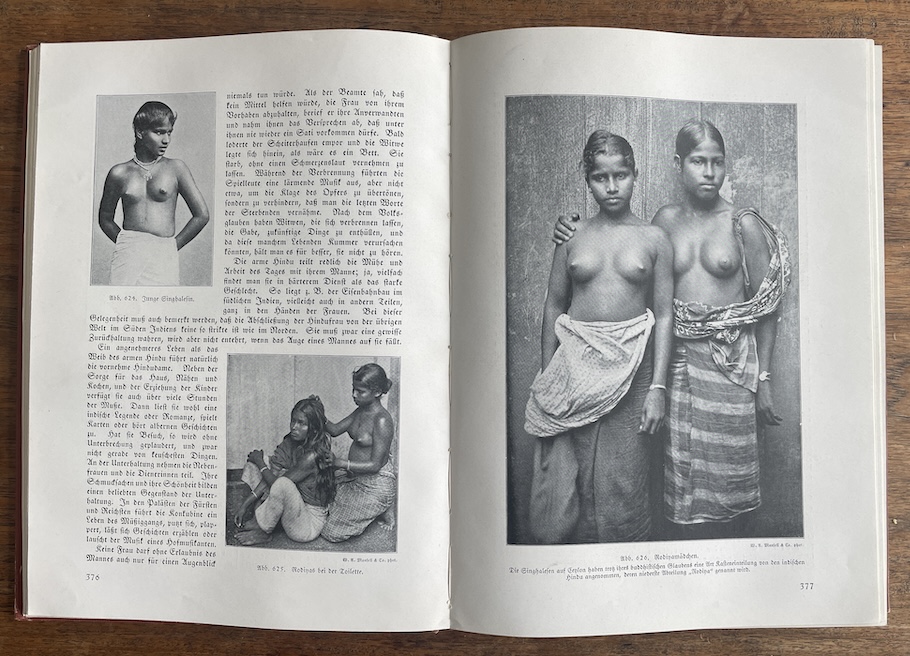

A double page spread from Das Weib im Leben der Völker, by ethnologist Albert Friedenthal, originally published by HKV in 1910, with an introduction by Ferdinand von Reitzenstein. The volume aims to capture the essence of the ”fair sex” via photographs of four hundred distinct ethnicities. Its mix of scientific language and salacious imagery serves as a perfect representation of its Zeitgeist.

Oh, I know what you are thinking: that volumes featuring photographs of women of exotic origin (naked but for their purported ethnographic value), will sell better than books reproducing rare rock paintings by our pre-historic ancestors. Oh, I won’t dispute you there. And your Klemm had enough mercantile – one might even say reptile-like – sense to recognize an opportunity when he saw it. All one had to do, in order to turn unclothed female flesh into solid gold, was wrap it in scholarly gauze. So your slyboots of a great grand-sire hit on the trick of framing plates of voluptuous native girls with texts couched in scientific jargon,“inter-cultural morphology“ and the like – much of it stolen from me – and abracadabra! these volumes leapt onto university (and less exalted) bookshelves across the Fatherland. This Klemm was no scientist, rather an alchemist of sorts – I won’t deny him that.

Now it could have been as far back as 1910, certainly before the War, that Von Reitzenstein or Friedenthal, I don’t remember which of the two it was, showed me the proposal they were presenting to Klemm, Das Weib im Leben der Völker (Woman in the Life of Peoples). And oh, they were thrilled by the possibilities with which he had beguiled them – some new printing process – one that allowed even moderately-priced books to be filled with first-rate photographic reproductions. Lord knows they had plenty of exotic “specimens“ to choose from. So there you have it – opportunity favors the mediocre and the venal. Alas, this seems to be one of Nature’s immutable laws!

Still, I can almost understand their temptation. Why not take what profit you can from the anonymous, dusty, sweaty field work of others? All one needs is to skim off the eye-catching cream of your archive and, aided by technological wizadry – secure the backing of some willing idiots. Slap your name on the cover, et voilà! Having barely lifted your dainty professorial hand, you are credited with authoring a seminal work in a field about which you know essentially nothing. Only a fool would actually devote himself to authentic scholarship, and that fool would be yours truly. At least in their eyes. Oh, but they knew I saw through them.

Shall I tell you what makes this pair of “colleagues“even more irksome? Their propensity to imitate me in look and gesture and rhetorical form. Why they even purchased pocket watches identical to those favored by Frobenius. A laughable exercise – as if that would transform them into true scientists. When I visited the Kaiser in exile and told him of their mimicry, he laughed and confided his belief that von Reitzenstein and Friedenthal were attempting to ape his personal style, especially his mustache. That was nonsense, of course, but who was I to disabuse poor Wilhelm of a notion he thought flattering? It would have meant telling him that these two sycophants thought less of him even than they did of the Communists and brownshirts.

Of the pair, Albert Friedenthal was as ignorant of the world as he was of science. Sublimely untouched by reality, he even put himself forward as a participant in the annual symposium held at his Majesty’s residence in Holland. I had initiated the program mostly to amuse the Kaiser, but it also served to keep the money flowing for my expeditions. Poor Wilhelm always looked forward eagerly to our gatherings – the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Haus Doorn, as it became known. Can you imagine? Friedenthal had the nerve to propose a lecture – graphically illustrated! – on the findings in his and Von Reitzenstein’s book. Did he not realize that the audience would include the Kaiser’s wife? I’ll admit to being greatly relieved when he died unexpectedly, thus saving himself from the disgrace of having his proposal denied.

A surprising friendship blossomed between Leo Frobenius (2nd from left), and the deposed and exiled Kaiser Wilhelm II (right). Frobenius humored Wilhelm’s fascination with ethnology at least in part in order to receive financial support for his expeditions and a lifestyle which included a retirement villa in Italy.

Ah, young man, you wish to change the subject. To what? My alleged transgressions in Africa? I advise you as I would any sane person: pay no attention to rumors. Rather look to my work, wherein I wrote both lovingly, and accurately, of the Continent and its people. Of course my approach, my scholarship, provokes hostility in certain lesser minds, in youth who respect nothing but their own prejudices, and in particular those half-wits who have become infatuated with our Anglo-Saxon cousins. Look to the work itself and you will find a triumph that few if any in my generation can match.

Do I hear you correctly? You want to know if Frobenius conjugated intimately with the women of Africa? Of course! And why should he deny it? For he did so always with the deepest affection. Any man of experience will tell you that sometimes there is just no way of fighting ardent women off, or of refusing them without causing offense. They were, for the most part, not merely beautiful, but adorably innocent of mind, always laughing, smiling, yet filled with fire and passion unknown to their European counterparts. Nor did they fall to weeping when we said farewell, unlike my dear and beloved wife who I sometimes had to chastise into silence. The women of Aftica, on the other hand, chanted merrily as our caravan moved on.

Since you are so diligently noting down my words, I wish state for the record that I stand firmly against the burning of Albert and Ferdinand’s books. Indeed I was appalled when I heard of it. Had I been in the Opernplatz that day, I would have snatched their volumes from the hands of that ignorant rabble. But I was far away in Africa when this disgrace engulfed our Nation. Your Klemm, I am certain, would have rolled in his grave at the fate of his books. Even his Majesty regretted not having spoken out more forcefully against the brownshirts at a time when his words might still have found attentive ears. But what power did he have by then? Came the disaster of 1918 and the Volk slipped from his grasp like a wriggling fish – one that in its desperation cannot distinguish between the man who wishes to return it to the stream, and he who will kill it.

Ah, you see, if one digs deep enough, the forgotten comes to light. At last I remember when Klemm first came to me. It was with the proposal for Die Gegner Deutschlands und seiner Verbündeten – sometime around 1916. Here is a Hauptmann der Reserve, I thought, wounded at the Maginot line – this fellow is looking for a hand-out. But as he lost no time telling me, he had, in all modesty, built a decent-size publishing house and, being indefinitely excused from active duty, was back in Berlin pursuing whatever it is that publishers pursue. At any rate, he knew of my privileged access to the Kaiser. Nor did he make any secret of his admiration for my work.

”Herr Professor Doktor,“ he said, “I am aware that you are presently engaged in a scholarly study of the inmates in our prisoner-of-war camps. Permit me to say that I find this a thoroughly worthwhile and praiseworthy undertaking. I am informed that your assistants are endeavoring to record all that may be known about these captives and their origins. Also that your draughtsmen are making portraits of these enemies of the Reich – men of all colors, religions and ethnicities, who have little in common besides having been pressed into service by the British war machine.

“Now while I find what you are doing most impressive and laudable, as a publisher, I ask myself: Why stop there? Might we not send artists of real talent to portray the prisoners – men of the brush who can render these captives so authentically that one would think they stood in one’s living room? If you agree to what I propose, we can begin at once. I do not boast when I tell you that the services of several excellent painters are at my disposal. What do you say to this: a grand juxtaposition of your ground-breaking scholarship illustrated with figure-portraits taken vividly from life?“

Well, young man, there is your Ur-Opa in a nutshell. Somehow, too, he must have known that his Majesty, the Kaiser, had just appointed me, Frobenius, to the post of Kommandant at one of those self-same camps.

Frobenius was the primary contributor of ethnographic texts to Die Gegner Deutschlands im Weltkriege (Germany’s Adversaries in the World War), Klemm’s monumental, lavisly illustrated work published posthumously in 1925. Most likely Klemm and Frobenius had been in communication about the project since 1915. Despite the extent of his participation, Frobenius never made any public mention of the book, or its publisher.

To be continued in our fall issue after a summer hiatus.

* * *