The Vanished Publisher II

Tobias Meinecke & Eric Darton

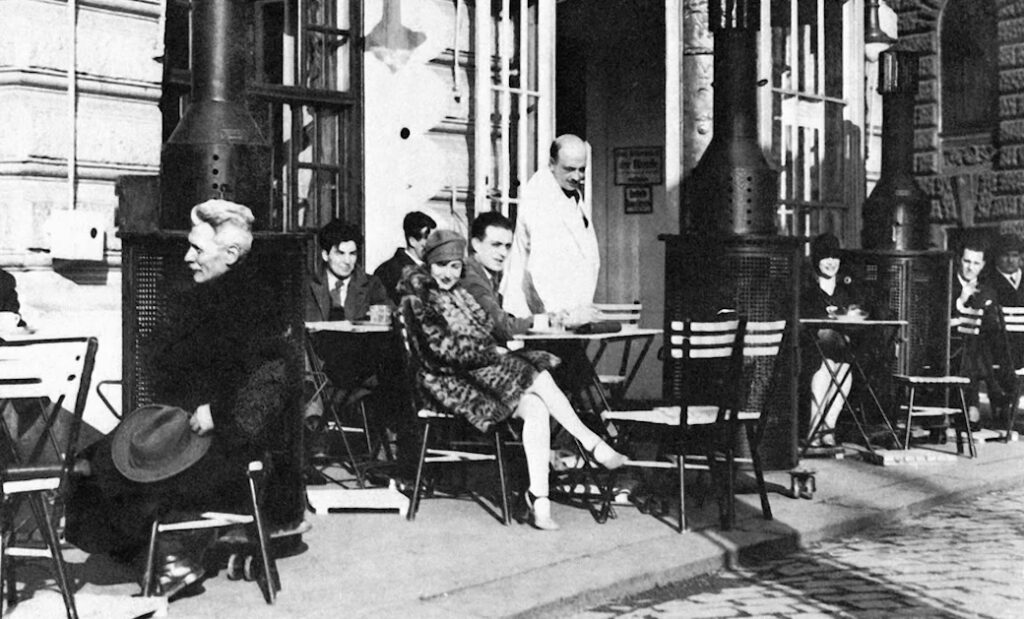

The Café Landtmann, Vienna, shown here in 1921, was a known hangout for spies of all nations and ideologies. Tantalizing evidence has emerged that this photo was taken by a Russian agent minutes after Trebitsch Lincoln met Adele Seidenadel here.

Berlin, 2022

Dear Reader, remind me where I left off. Ah yes, the Frankfurt Book Fair of ’21. And in particular my conversation with the mysterious lady, who, with the hint of a smile, fixed me with those blue-green eyes and said: “What a long way you’ve come, Herr Klemm.”

“A long way from where?” I almost replied, but thought the better of it. “I have been blessed with success, Madame, if that is what you mean.”

“You don’t know who I am, do you?” she asked.

I had to confess I did not, despite racking my memory over the question. She seemed like someone I should know. Perhaps a famous actress or singer? The latest offspring of some ancient noble lineage?

“It’s not important. But we’ve met before.”

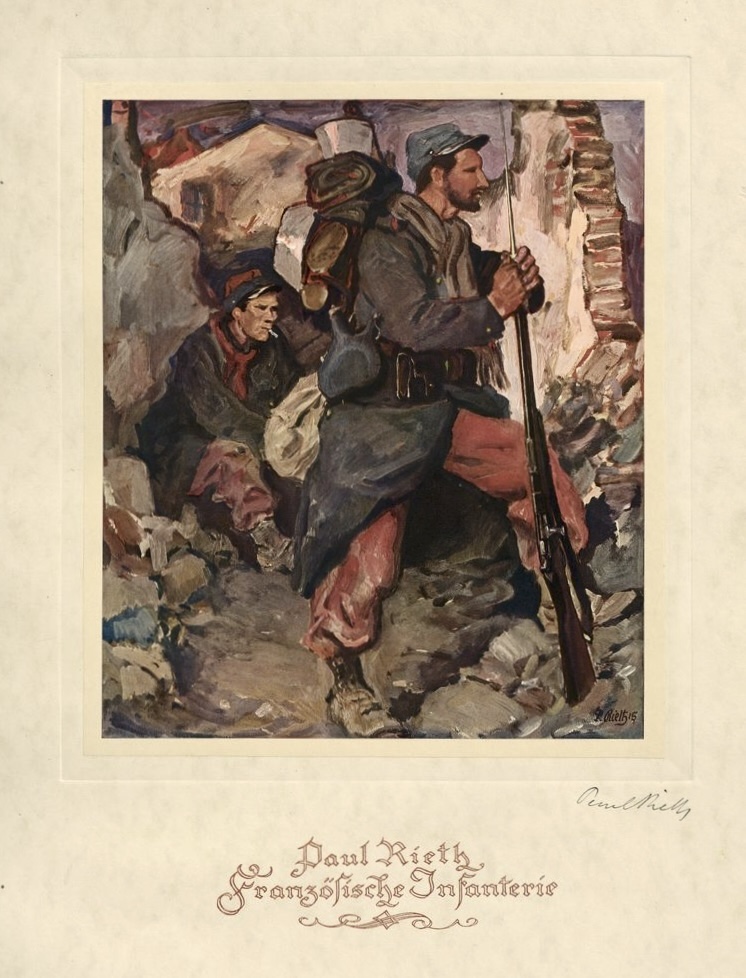

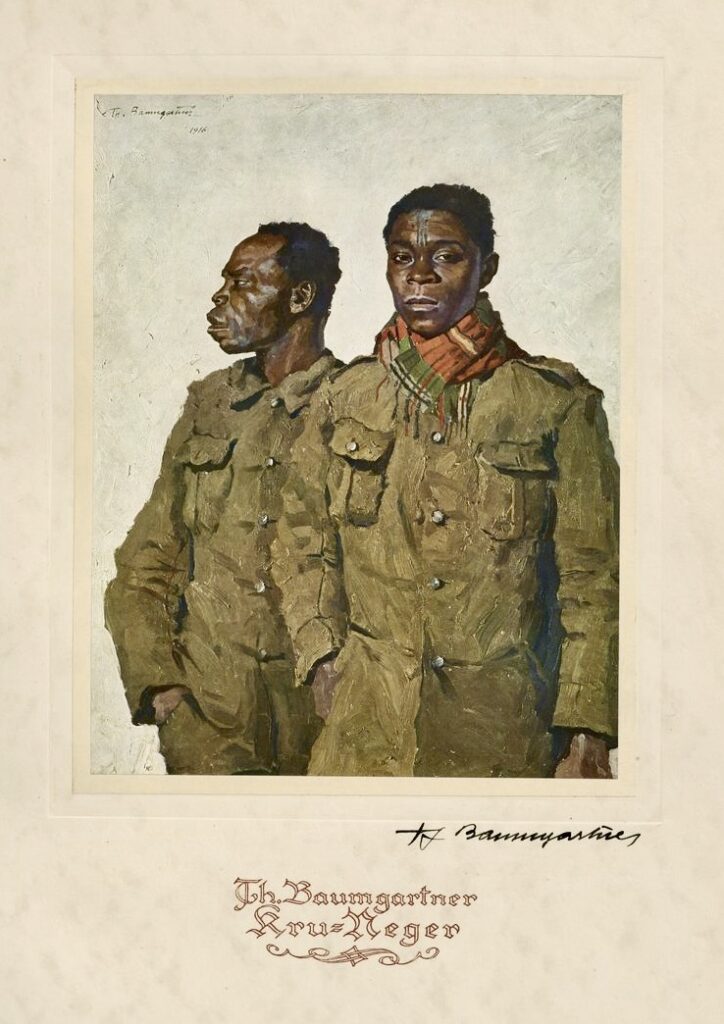

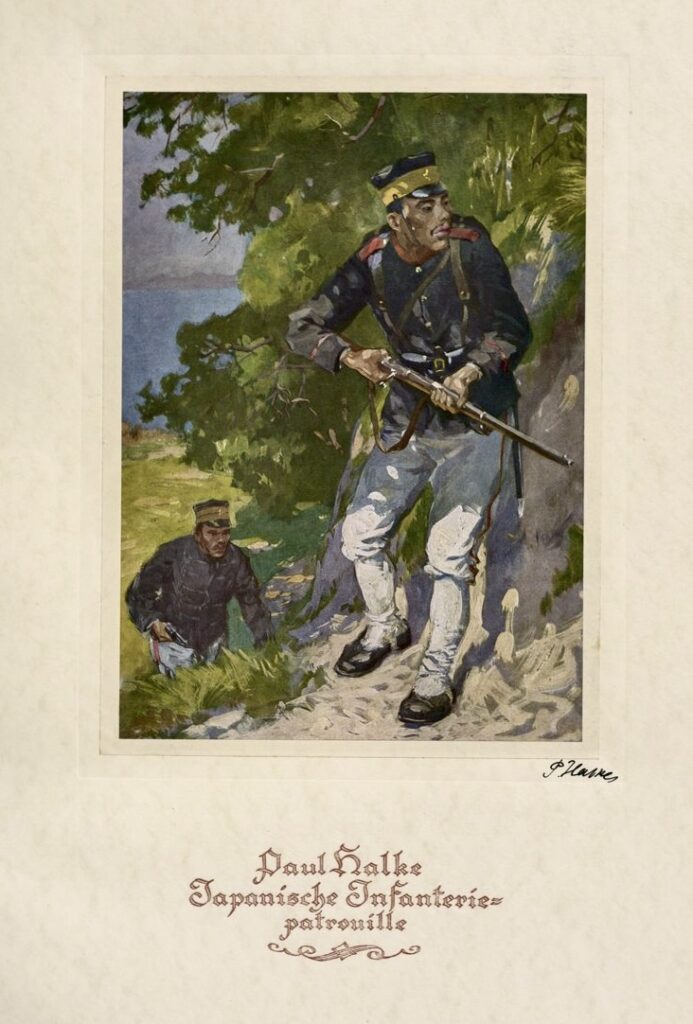

Turning her attention to the portfolio I had placed before her, she regarded each of the two dozen illustrations of captive enemy soldiers with apparent interest. Was it genuine or merely polite? When she had finished, she closed the cover and handed the proofs back to me with a smile. “As always, your house produces only the finest quality. Thank you. I must be going.”

“One last question, Madame, if you please.”

“Of course, Hermann. I may call you that, yes?”

I nodded in the affirmative and, if such a thing were possible, her expression became even more beguiling.

“Did you purchase the entirety of the other publishers’ offerings as well, or are we the only ones to be so honored?”

She paused, and for a moment I was not sure she would reply.

“I regret, Hermann, that I am not at liberty to discuss my transactions at the Fair. But your fellow publishers can, I am sure, provide you with the answer. I wish you all success with your future endeavors. And now, adieu. My porters will be here shortly to pick up the books.” And with that she stood, we shook hands, and she departed.

Indeed, soon afterward, two fellows arrived from Frankfurter Hof bearing a trunk into which we packed all the volumes. Then they set off, pushing their trolley cart toward the railway station.

Three plates from the monumental folio Deutschlands Gegner im Weltkriege (Germany’s Enemies in the World War), proofs of which may have been shown to Adele Seidenadel at the Frankfurt Bookfair of 1921. From left to right: French Infrantrymen; a Kru soldier (member of a seafaring people of West-Africa); two Japanese footsoldiers on patrol. The respective artists names appear in signature and print below the plates.

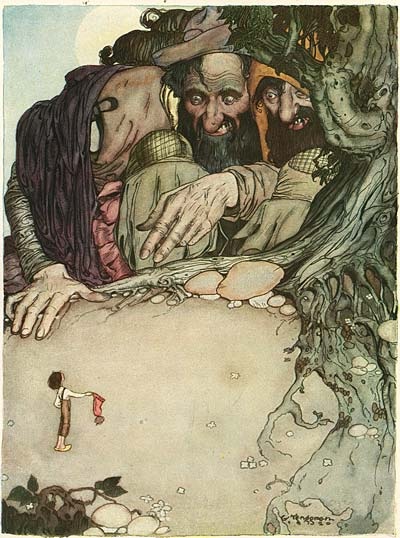

So now, my friendly pokers and prodders, and readers all, let me tell you something: I have seen war, real bloodshed on the field of battle, which some call honor. Moreover, I have survived, even prevailed, in business – which resembles warfare in more than one particular. But mystery – there’s been precious little of it in my life. The great love between Alma and me? That was a matter of immediate passion – which endured as well as it could through the years. But that moment in Frankfurt, that briefest of meetings, suggested to this reluctant romantic nothing less than the possibility of unbounded promise – beyond even pleasure. So here I am, a hundred and one years later recalling those clear, bright blue-green eyes as they traveled swiftly over the lines of text my typographers had set, and widened to take in the images of Tahitian nudes and prisoners of the Reich, but most of all Baluschek’s glorious illustrations of little Peterchen and Anneli, flying off to the moon with their maybeetle friend, Herr Summsemann, on a fairy-tale mission to break his crippling curse.

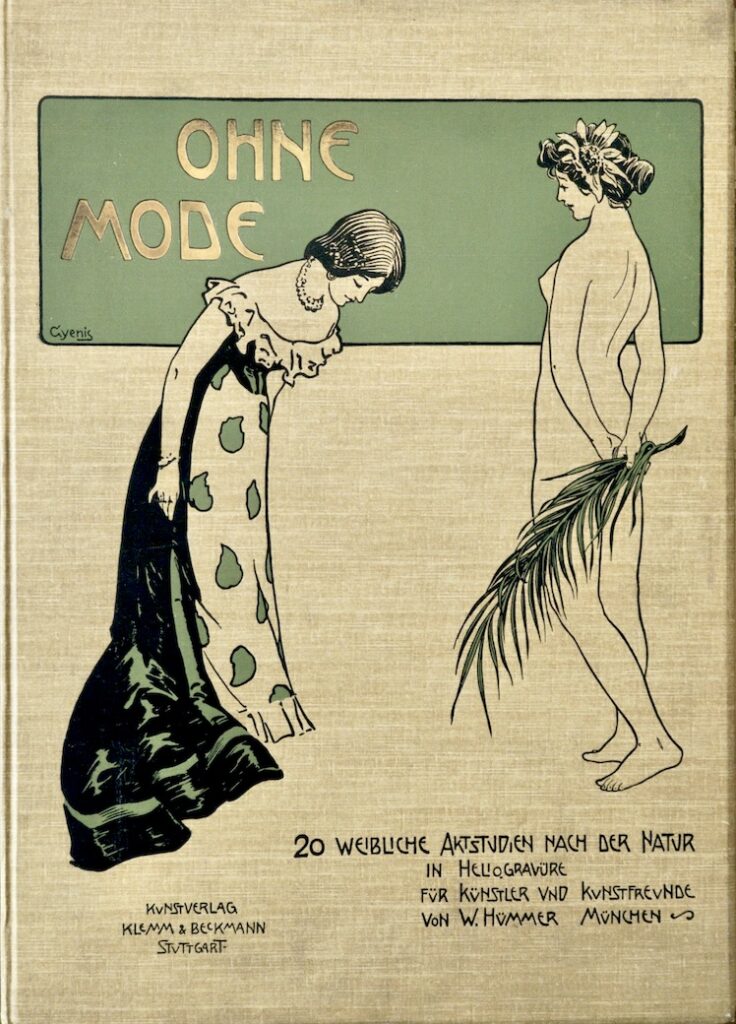

The cover of Ohne Mode, the folio of nude photogaphs that marked the beginning of Klemm’s rise as a publisher. It includes images which possibly depict Adele Seidenadel.

Mid-Atlantic, 1931 – on Board the SS Bremen

What is it to be a Nude?

From the moment I recognized the urge to become that so charged and provocative an entity, I have been of the belief that the impulse to appear willingly and freely undressed in front of others – for art or for pleasure – is rooted either in the desire to be seen for who one truly is, or to construct one’s self as a fantasy, a thrilling object for a voyeur – and, via a curious alchemy, for the Nude as well, if she acknowledges this experience as her right.

Which of these two Nudes will one choose to be? I chose both.

Anyone who lived through those searing July days of 1902 would have wanted to disrobe if only to feel the slightest breeze upon one’s skin. It was already stiflingly hot at breakfast when my friend Liesl showed me an advertisement in the paper; we’ll go together, she said, but at the last minute got the vapors – one could never count on her. So, I went alone to have my twenty-year old naked body immortalized on a silver plate in the darkened studios of a Munich photographer. The venture had been initiated on a whim, but once I was there, and glimpsed the numinous pool of artificial light, and smelled the air of powder and make-up I wanted, with every ounce of my substance, to be seen as the woman I felt I was. She who stood there, waiting to be posed, was not some bonbon giftwrapped in swaths of cotton and lace to be paraded along the boulevards on the arm of a black-clad manikin. Nor was she one to hide indoors protecting the few inches of porcelain skin that fashion decreed might, in those days, be publicly revealed. No, she felt alive within her form as never before, every hair on her body beckoning the light to stroke her flesh.

Now the patron of this artistic endeavor had glanced over as the matron helped me out of the corset, and when I turned to face the blue-eyed fellow his face froze for a moment, slack-jawed in wonderment before he looked away. I did that, I thought. And despite the poor man’s determined expression, he kept popping out of the shadows on some real or imagined errand, each time casting his gaze my way.

Now he whispered to the photographer, and I overheard him ask if any of the models could be induced to pose outside, in “nature“ as it were – say in the park, by the lake… and before the words were asked I called out: Ich wäre dazu bereit, mein Herr. At which instant, my silken robe slipped off and pooled about my feet, and now his face turned redder than his hair.

The next day the heat broke and the sunlight felt as though it were all I needed to wear. And by extension all else seemed pleasurable, not least the lunch excursions we took to the beer gardens. I laugh now at how my younger self responded with an almost aggressive seductiveness to the young publisher’s pretension of being all business, occupying himself in the back of the studio with reading a book, or shuffling some papers. After one of the shoots, I made it my business to provoke him. I found some excuse to pass by his desk and allowed my robe to slip open revealing what was, and I’ll admit remains, as lovely a nipple as may be found in art or nature. The poor fellow was leaning back in his chair, and like a character in a silent movie, he made an involuntary pantomime of nearly falling over backwards, before awkwardly righting himself and grasping his desk as if it were the edge of the world itself. I couldn’t help it, I burst out laughing. And to his credit, so did Klemm.

After those sessions in Munich, I never again undressed for the camera. I never felt the calling, much less the desire. Why chase the warmth of the carbon lights, or the sun itself? The eye of the lens had drawn forth my spirit to meet it, and that encounter was sufficient.

But if I was done with those Munich days, they were hardly done with me – though it took twenty years for the circle to come round. How did they find me, these shadowy conspirators – whose representative became my Client? Did they know, via some informant, about my past connection to Klemm? Were they aware of my never-quite-subsided fascination with the man? Or did they choose me for altogether different reasons? One thing’s clear: they were entirely confident I would agree to work for them.

Though to this day I cannot tell what led them to me. Certainly not my likeness, for neither my name, nor those of the other models were listed in the folio. I was paid in cash in 1902 and, moreover, had given the photographer a stage name and the mailing-address of my friend Liesl. In short, my body’s image floated free of any lines by which to trace me. Still, somehow, they sought me out – the perfect instrument for their plan.

Now I should add that after the folio was published, Hermann attempted twice to contact me. Liesl forwarded the correspondences. And on both occasions I agonized over my response.

First came a generous offer to pose for twenty additional plates of nudes, some to be hand-colored, for which I would both be paid and receive publishing royalties. The fee alone would have covered my expenses for a year, and some finery besides. To this letter Klemm had, for reasons about which I could only speculate, but nonetheless caused me a few wakeful nights, attached a photo of himself and his bride Alma, a somewhat round-faced, not to say plump young woman, whom I will admit, possessed a pair of lively eyes. Needless to say, the happy couple was quite overdressed, as was the conventional fashion of the times before the War.

Alma Klemm (née Beer, standing) with twin daughters Ilse (left) and Hilde (right), and her mother Alma Beer (née Schwarz, kneeling). Summer 1906.

The second letter came about year later: an invitation to a formal presentation of the Ohne Mode folio, in which I was featured, in addition to several other books of nudes, presumably those which I declined to pose for. The event was to be held under the auspices of the Akademie der Künste, at an artist‘s studio in Schwabing. They’d lined up some big-wig professor to explain why photographs of lovely, languorous unclothed women must be considered Art. I’m not sure why I did not respond to either offer. I was interested in Klemm. But something held me back.

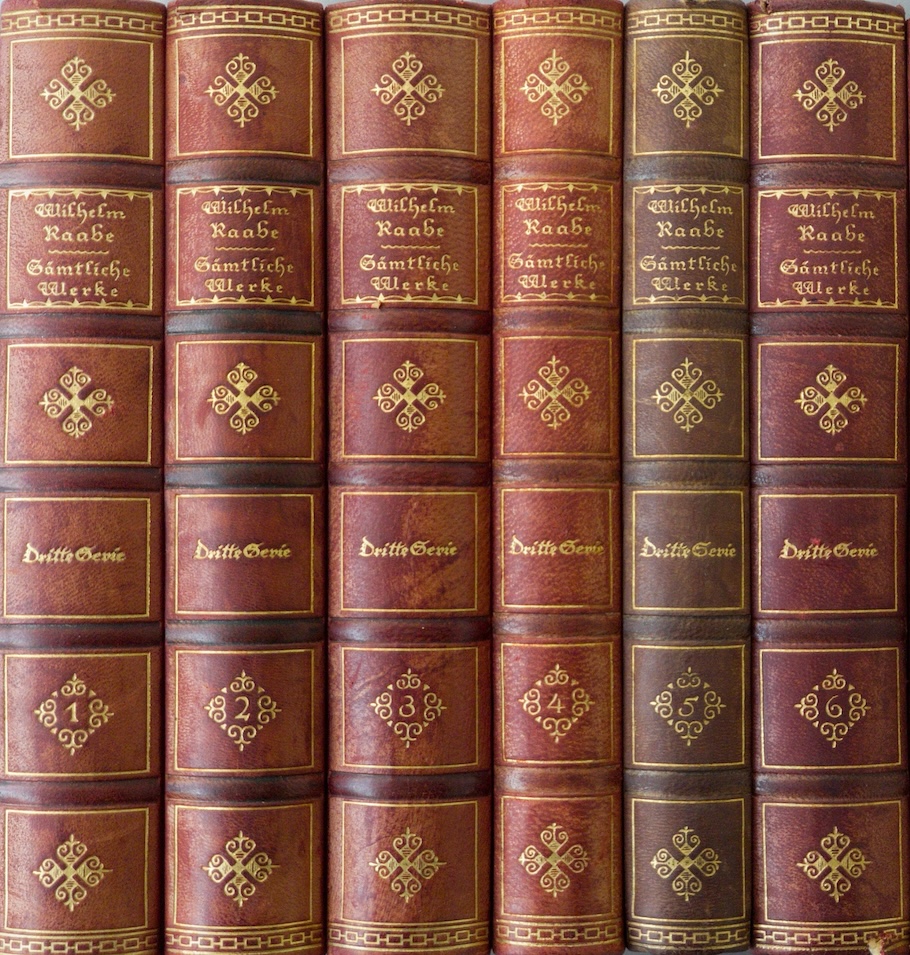

A few years later I heard the Verlagsanstalt had moved from Stuttgart to Berlin. Also came reliable reports that Hermann and his partnershad landed in a maelstrom of financial troubles, largely due to the now-zealous enforcement of the Lex Heinze, i.e. the banning of all “nude” images that fell outside a very narrow artistic definition. I learned, too, that Klemm was in the process of pivoting toward the publication of other kinds of books: children‘s books, high-quality reproductions and monographs of painting and sculpture, handsomely produced anthropological almanacs, and, most importantly, Literature with a capital L. Somehow, this knowledge of his evolution, never quite displaced my earlier impressions – of a man who, whatever his talents, could not be pinpointed or held to a rigid point of view.

Without going into unnecessary details, let me say that as the years passed a host of occupations, pursuits, and indeed liaisons with men of greater or lesser interest, eventually consigned to shadowy dimness my memory of Hermann Klemm. So when, in preparation for my mission at the Frankfurt Book Fair, I compiled a short list of publishers worthy of my Client‘s consideration, Hermann‘s Verlagsanstalt was not on it.

So now you may imagine me, nearly two decades after my Munich adventure in undress, entering the grounds of the Fair on the finest of September mornings. There, at the threshold stood a large painted sign listing all the exhibitors and their locations. Which I duly studied to determine in which order I would approach my prospects, then saw, almost to my surprise, the words: Hermann Klemm; Verlagsanstalt für Kunst und Literatur AG, Grunewald.

It is precisely for such moments that a certain type of women, those more worldly, perhaps, than I, carry a small flask of liqueur in their purse – not smelling salts, but something of sufficiently high proof to help them find their footing when unexpected circumstances have made them wobbly.

But I am not that type, much as in the instant I wished otherwise. The sign before me swam, my breath came short, my heart pounded. Gottseidank bin ich allein (Thank God you’re by yourself), I thought, and Wie lächerlich mache ich mir hier (Isn’t this ridiculous)? Had I secretly, and without admitting it to myself, carried a torch for this man all these years? He was not, I knew myself well enough by then, even my type. Perhaps seeing his name evoked the resurgence of a distant former self, whose sudden appearance caused a disconcertion of my whole body in space and time.

Immediately I flew to the paranoic, and why not? My Client must have known, and set me up! And the truth was that he, they, seemed to know so much about everything. It felt as though they – they! – were putting me to some test, whether for reasons of their own or simply out of cruelty. Just what did they wish me to do? Avoid Hermann? Or target him?

I chose avoidance and for two days took pains to make big circles around the corridor of stalls where the Verlagsanstalt was situated, or, in moments when that wasn’t possible, strode briskly right past it, my gaze fixed firmly ahead. And I found myself busy enough to put off the inevitable. By the third day, though, it was clear that the other publishers I had painstakingly investigated were either uninspired in quality, questionable in business practice, nakedly opportunistic, or politically too far to the left to be useful to my Client. So I approached Klemm’s stall – with trepidations.

Staff of the Verlagsanstalt circa 1906, when it was still based in Stuttgart and operated as Kunstverlag Klemm & Beckmann. Standing from left: Beckmann (1st), Klemm (3rd), Hourch (5th) and Alma (7th).

What would he look like, twenty years on? Hair, thick or thinning? Well stuffed into his bourgeois suit? Cheeks red from drink and sausages? I assumed he still wore a mustache. Nor was anyone fitting his remote description to be seen as I entered. Instead, I encountered two of his employees. Front and center stood a fellow named Hourch assisted by indecipherable factotum who I saw typing away in the back with an urgency that suggested business had been brisk. Yet this morning, no other prospective customers were about.

With a hand whose trembling I worked hard to subdue, and an air of what I hoped conveyed nonchalance, I began leafing through the books on display before me. From time to time I looked around. Was he really not around?

Hourch moved close enough for me to ask without raising my voice if they had titles in reserve that were not on display. “Such as, Madame?“ he asked in a pleasanter voice than I would have expected from his demeanor. I told him and his eyebrows ascended nearly to his hairline. “Ohne Mode, Madame? Did I hear you correctly? Why that folio datesfrom 1902 – it was the first major undertaking by this publishing house. Of course, we have a copy. But it is not for sale.”

“That is a shame,” I said, and recited from memory a passage from the introduction. Now the fellow was truly astonished. How was it possible that eine so junge Frau as I knew of its existence?

I replied that I was scarcely as young as he thought me, but Hourch seemed not to hear my response. Rather he launched into a breathless recollection of the early days of his apprenticeship, when Klemm and Beckmann, Hermann’s former partner, had found the inspiration for the folio. It was one of his great regrets that he, Hourch, had not been in Munich for its production. His boss, he whispered, had told him he was too Catholic for such things. “But the truth is, I think he was hoping to have the pick of the models for himself – without competition. This was just before his marriage, and perhaps he wished to – “

To derail his continuation along this line, I asked: “Might the Verlagsanstalt re-publish the folio in the future?”

Hourch shook his head vehemently. “Absolutely not. Times have changed. The world has changed. Today Ohne Mode would either be too little, or too much, you see! Not enough titillation for some, or too much of it for others, depending on who you are talking to. These days,“ and here again he lowered his voice conspiratorially, “it is difficult to know who your customers might be, and who your enemies.”

“What if another party were to finance its publication?“

“Even if someone offered to back it Klemm would refuse. He has an unerring nose for where the market is, and will be going. His eye is ever on the future. On that he’ll gamble – but mind zou with calculation. But looking back? No – the man has zero romance with the past.”

I felt a pang. Ought I to ask Hourch to show me a copy of Ohne Mode? After all I had never seen it. But what pleasure or regret would that avail me, twenty years on? No, I decided to make polite talk while I browsed and waited for Hermann to appear. Which, some intuition told me he soon would. In the meantime, I allowed myself to enjoy a thorough exploration of Klemm’s books, nearly infinite in their variety, yet all, somehow forward-looking, even those held to be classics.

I had to stop myself from whistling. A small but real triumph had occurred, and does one not wish to succeed? I had found, at least to my satisfaction, the one publisher who could fulfill my Client’s purpose.

“Find us a German publisher who might be receptive to our cause – or in any case one who is not by nature hostile of our aims. In short, a solid, middle-of-the-road German, not some rabid Royalist, nor one of those progressive subversives. Such a publisher will permit us, from time to time, to insert certain material into his books – material which, of course with subtlety, advances our goals. When you have determined who this publisher is, prepare a report on those volumes which best lend themselves to our objective. Finally, who are the buyers and readers of this publisher’s books? What is their social status? Take the measure of their political affiliations, attitudes and beliefs. In short, paint us a detailed portrait of the publisher, his esthetics if he has any, the workings of his business mind, and the propensities of his customers.“ Such was my Client’s mandate.

Who was my Client? I will tell you frankly that I did not know. I did, however, meet a middle-man the summer before the Fair – and this at Café Landtmann, in my home town of Vienna. Ah, the Landtmann – for all I do not hold in common with Herr Sigmund Freud, this café is a place of both our hearts.

Now my meeting with said middle-man had been arranged by Alphonso Ludvigo Graf Pace Freiherr von Friedensberg, a former lover of mine – of whom little need be noted apart from his reluctance to scrutinize the ethical dimensions of a potentially lucrative venture. My sense was that Alphonso hoped, should the connection between myself and the middle-man prove fruitful, to be rewarded in terms material or romantic, and preferably both.

Now although I was punctual, even a few minutes early, the man I was to meet seemed to have arrived considerably earlier, judging from the several checks already wedged beneath the ashtray. I had not seen him there before, but noted that the waiter treated him with the deference due a man whose chief quality is to appear powerful by representing those who genuinely are.

The fellow, without doubt, possessed a kind of electric energy. His demeanor seemed calm, yet there was a watchfulness to the eyes that betrayed a constitutional nervousness. Nor could I help but wonder how Herr Freud would analyze him. He proved most incurious about his prospective employee, much less my fitness for the job, or willingness to do it – rather treated our interview, from the outset, as a set of directives to an attentive subordinate.

He was, therefore, surprised, and not altogether pleased when I asked “And what is the aim, sir, of those you represent?”

“That, Madame, you will be told when it is deemed necessary, or appropriate for you to know. Not before, and possibly never. The matter, however, is of considerable importance to the future of the German Reich.”

I stood involuntarily. It was not a tactic, but it worked like one.

“Please be seated,” he said, with an attempt at geniality that seemed to cost him dearly. “It is the urgency of the matter that caused me to be abrupt. May I count on your consideration of my offer? If so, please contact me at your convenience.” This time we rose together. In parting, he handed me his card, and tipped his hat.

On the tram, I read his card: Trebitsch Lincoln; Berlin, Budapest, Vienna, London, New York, Zurich – this engraved in elegant print on very fine paper. What a strange name, and stranger accent – not native to any of those places. Indeed, he sounded like my dear late brother-in-law, a Galician Jew.

In response to my note accepting the assignment, I received a single line in reply:

“You’ll hear for me after the Fair.”

“Däumling,“ one of thirty-six illustrations by legendary Swedish artist Gustav Tenggren (later a lead artist at Disney) for Grimm‘s Märchenschatz (1923), one Klemm’s final projects.

Berlin, 2022

Once you are where I am, which is without name but, if you will trust my first-hand knowledge, is what people mean when they speak of the Realm of the Dead, it does not matter whether you died yesterday, a hundred, or two thousand years ago. Nor whether you were Hermann Klemm of Rügen, book publisher and Hauptmann (retired) of the German Army, or Hermann the Cheruscian, a “barbarian” who delighted in personally decapitating his prisoners-of-war after the battle of the Teutoburger Wald, where his Germanic tribe annihilated the Roman legions. It makes no difference whether you lived a happy or miserable life, were a success or failure, found love or didn’t, enjoyed the respect of your fellows or garnered their contempt. None of this matters, because when I assured you earlier there was nothing here I really meant nothing. Nichts. And whatever one might have felt or thought in a life time no longer holds any importance.

Still, since certain people started to lay out the details of my life like a display for all to see – even going so far as to publish my love letters to Alma – well, what can I tell you? When you have been nothing, been forgotten, and have likewise forgotten everything you once knew, it is very easy to let whatever arises happen, to allow the story to unfold, to permit your own life to roll over you. As if you are a spectator standing in the middle of a thunderstorm, protected from yourself.

So then, why not? Let’s hear what’s next.

The Collected Works of Wilhelm Raabe (3rd series, Vols. 13 – 18). Raabe was the first of several eminent writers in danger of being forgotten whose work Klemm successfully reintroduced to the public.

* * *