The Vanished Publisher III

Tobias Meinecke & Eric Darton

Klemm’s Great-grandson Boris Weidemann, one of the initiators of the Klemm revival, at the inaugurating event in Berlin-Wannsee, November 2022 – 100 years after the death of Hermann Klemm. Photo; Joachim Gern.

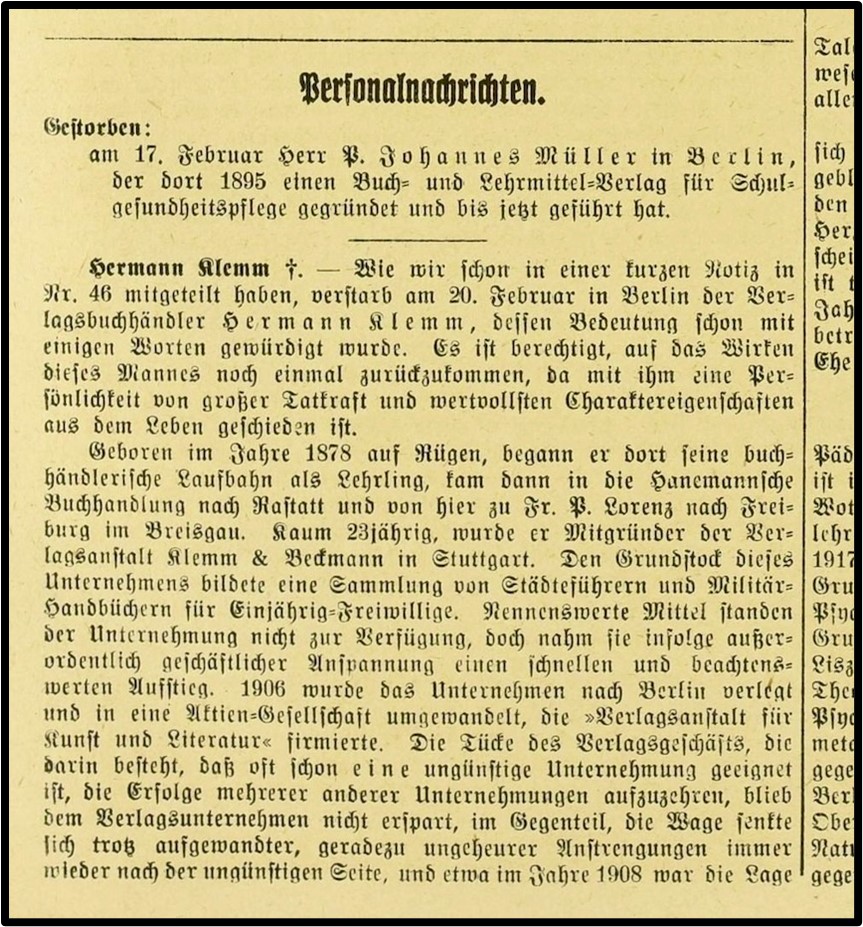

From the Börsenblatt Des Deutschen Buchhandles, March 4, 1922.

As was already mentioned in a short note in Vol. 46, the publisher Hermann Klemm died in Berlin on February 20. Although the importance of Klemm has already been widely hailed, it is justified to return to the work of this man in more detail, for a personality of great energy and distinguished character has left this life.

Klemm’s Obituary in the Börsenblatt des Deutschen Buchhandels, Issue 54, 1922.

Born in 1878 on the island of Rügen, Hermann Klemm began his career as a bookseller’s apprentice there, then went to the Hanemannsche Buchhandlung in Rastatt, Baden, and from there to Fr. P. Lorenz in Freiburg im Breisgau. At the age of barely 23, he became a co-founder of the publishing house Klemm & Beckmann in Stuttgart, starting with a modest but highly regarded collection of city guides and military manuals for one-year volunteers. The company did not have any significant start-up funds at its disposal, but nevertheless experienced a rapid and remarkable rise due to the founders’ extraordinary business acumen. In 1906, the company relocated to Berlin and was converted into a joint-stock company, which traded under the name of Verlagsanstalt für Kunst und Literatur.

The publishing business is often characterized by the danger that one unfavorable undertaking can consume the income of several successful ones. The Verlagsanstalt was not spared from this hard truth. On the contrary, the scales kept tipping to the unfavorable side despite the enormous efforts that were made, and around 1908 the company’s situation was such that its continued existence became impossible. The company was dissolved and Klemm took over the running of the business alone.

He now began an extraordinary, far-reaching and purposeful rebirth. He first acquired the individual editions of Wilhelm Busch, which were scattered among many publishers, and combined them into the now well-known “Neues Wilhelm Busch Album.” The extraordinary success of this undertaking (by today, 140,000 copies have been published) speaks louder than any critic could.

This undertaking was followed by a complete edition of the works of Felix Dahn, which was in turn followed by those of Gustav Freytag and Wilhelm Raabe. Klemm went from success to success.

Despite this, a failure forced its way into the distinguished offerings, when Klemm – in conjunction with the French government – began to publish the German edition of the French files on the diplomatic origins of the war of 1870-71. The project was planned to comprise 8-10 volumes, but after the publication of the third volume it became clear that the project would need to swell to around 30-40 volumes. Furthermore, the French government was facing enormous headwinds in Parliament because it had entered into a business relationship with a German publisher. As a result of this and the enormous scope of the project, commercial success in Germany could no longer be expected, and consequently all the costs and efforts expended on that project had to be considered lost.

However, Klemm was not one to allow himself to be deterred by any setbacks; in addition to the valuable literary enterprises mentioned above, he succeeded in bringing Gottfried Keller to the public, as well as Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach. The complete works of Lili Braun are currently in preparation.

Furthermore, Klemm created his collection of “German Fairy Tale Books,” which he opened with the volume Peterchens Mondfahrt (Peter’s Trip to the Moon), which has since had wide influence and distribution.

If one appreciates the significance of all these creations and takes into account that the war called Klemm into the field on the very first day and made unusual demands on him as a battalion leader, especially in the battles at Hartmannsweilerkopf, then one will understand that Klemm possessed a drive that far exceeded that of the average publisher.

I wrote that. Those are my words – written in haste and telegraphed to Leipzig five minutes before the deadline. And not just that. I stand by them today. What you read describes Hermann’s life as accurately as I could, and as fully as would fit in two columns.

It would have been past anyone’s imagining that my eulogy would be some day be read aloud before an audience of eighty gathered at a Villa on the banks of the Wannsee, less than ten kilometers from where Hermann took his last breath.

But the man in black delivering these words, my words, that tall lanky man wearing a beat-up top hat – I swear he looked like a scarecrow – that man was not me.

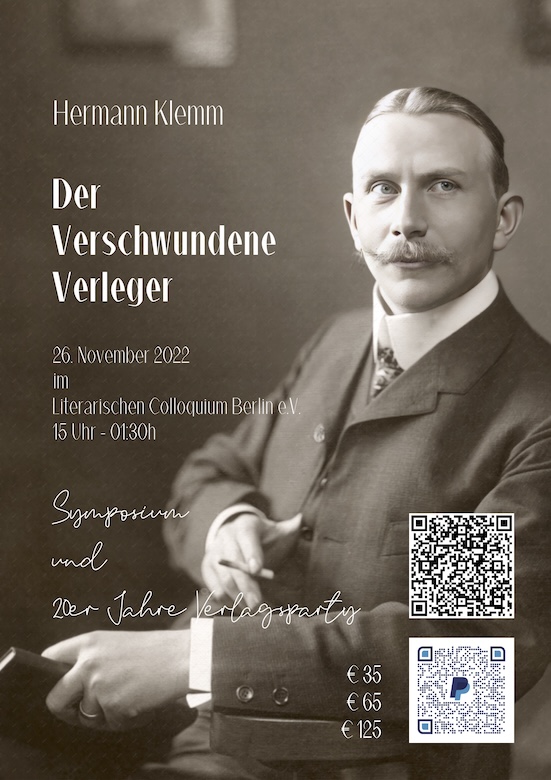

Poster for the 100th Anniversary Revival of Hermann Klemm, held at the Literarisches Colloquium in Berlin-Wannsee, November 26th, 2022.

No, this fellow reading Hermann’s obit comes onto the scene a full hundred years later – on November 26, 2022 to be precise. If you need a culprit for why we‘re suddenly all back, he’s the chief instigator. We being Alma, the twins, Beckman, Bassewitz, Baluscheck, Busch, Raabe, Fickenrader. And the list goes on. Yes, Mr. Tophat is the reason we‘ve been dragged onto stage and are looking at one another asking what in the world is happening? Who asked us for permission? The answer is: no one did. And if anyone had, even if they were one of Klemm’s great grandsons, we’d never have agreed to it.

But since we are here, and so are you, go ahead and read the rest of Hermann’s obituary:

Klemm’s great successes is too often attributed to the traveling bookseller trade. This is not correct. The turnover of the traveling bookseller trade amounted to only about a fifth of the total turnover of the company. With the Verlagsanstalt’s focus on Complete Works as well as on Collector and Luxury Editions, Klemm served the dedicated retail business above all, giving retail booksellers a wide range of objects which they gratefully took up.

Klemm took a special interest in Wilhelm Raabe, which is best illustrated by a few figures. In the years from 1863 to 1913, a total of 253,000 volumes of Wilhelm Raabe were sold, while Klemm distributed 1,179,000 volumes in the years from 1913 to 1921.

However, Klemm was not just a talented businessman, but had also acquired an astonishing knowledge of the production process, which is reflected in all his editions. For all these reasons, his passing is mourned far beyond the narrow circle of his immediate surroundings. It is said that an illness with scarlet fever in his 14th year was the cause of his early death; it led to a heart muscle contraction, which became serious about two years ago and now led to his death.

His fate can only be described as tragic, as it slowly but surely took a man in the prime of his life and at the height of his success, deeply mourned by his wife, with whom he had lived for 18 years in an extremely happy marriage, and by his two flourishing daughters.

— A. Hoursch

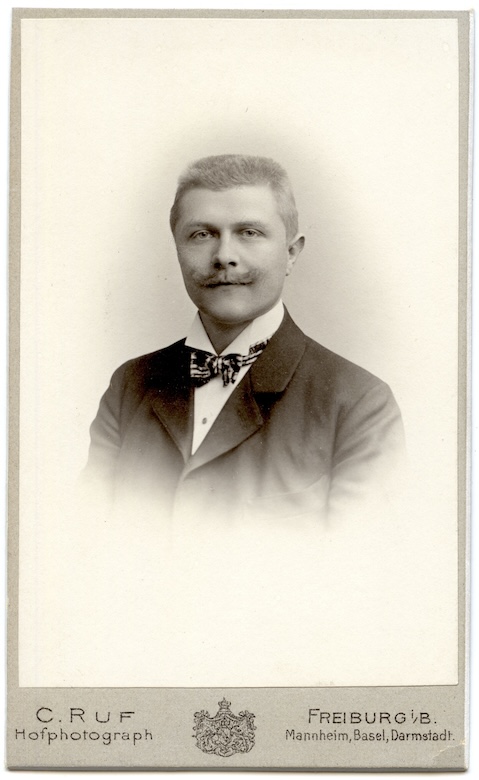

Front of a name card of August Hoursch, Hermann Klemm’s best friend and right hand man since their days as bookseller apprentices in Freiburg, where they roomed together at Bergstraße 13 in the years 1899 – 1902.

Not a bad piece of work, considering. I tell you, to be asked to write the obituary of the man who was not just your boss, but a friend – more than that, a kind of demi-god – is like doing brain surgery on yourself. But what made it worse was learning the news of Hermann‘s death not from Alma, or his doctor, or even from die Kupsche, his dragon-lady of a business manager. Indeed, none of the above.

Who then? I see it as clearly as if it happened yesterday: I walked into my hotel in Heidelberg, and along with the room key, the desk clerk presented me with sheaf of cables from Leipzig marked urgent – call at once. What is all this about? I wondered. Had the Börsenblatt gotten wind of Hermann‘s latest publishing coup: his scheme to issue a delux edition of Frobenius‘ mammoth volume on the enemies of the Fatherland with a frontisepiece personally signed by every German Division Commander from the Great War? Was Hermann’s maddest, most grandiose project about to hit the press?

Naturally, I called right away, but of course it had nothing to do with the folio. I’ll never forget how the underling on the other end of the line sounded surprised that I hadn’t already heard the news and – even as my knees nearly buckled – spoke of Hermann’s death if it was a run-of-the-mill news item. The truth is, when I didn’t respond to what she was saying, her voice grew impatient. “Herr Hoursch, are you listening? You must send us the requested material by 4 p.m. Otherwise, I cannot promise we’ll be able to publish anything on Herr Klemm at all. And again, no more than three hundred words, bitte.“

I should have been galvanized into action. But I felt entirely cut off from reality and for who knows how long I just stared out of the window, not knowing what to write, nor even how think in whole sentences. If even for a moment you imagine that the view from my room featured the beautiful Neckar and the magnificent castle above it, you are gravely mistaken. Alma kept the purse-strings tight. What I looked out on was a backyard between brick buildings featuring a single spindly apple tree, shunned even by birds, and a clothesline hung with laundry – illuminated for almost an hour if the day was bright.

But what lay outside the window and what I saw were two completely different things, for I found myself staring into the past – 1898 to be precise: Hermann, me, and that eternal joker Knobelsdorff playing cards all night, singing together in our ”La Boheme” maisonette in Freiburg, and guzzling enough Riesling to refloat the Scharnhorst.

And then I was back in Rastatt, at Zum Alten Ritter – glimpsing Alma for the first time, across a crowded room, as she enchanted – with no effort at all! – every young man who came within her magnetic pull. Would I have stood a chance with her? There were times I flattered myself I might have. But to be honest, no, never. When I walked in, no one raised their head – certainly not Alma. Oh she glanced at me, just as she did the other fellows, almost looking through us as if we were transparent. On the other hand, something changes when Hermann enters a room. Which, ten minutes later, he did, wearing his bemused expression, and scanning the scene with those light, nearly colorless blue eyes.

In my reverie, I had shut my own eyes and when I opened them a shadow had fallen across the scene outside and dimmed the room. I turned on the light and fed a sheet of paper onto the typewriter platten, thinking then as I’m thinking now: did Hermann consider me his friend, his equal? Perhaps in his heart he did. Though not when it came to publishing, of course. When it came to books, and an instinct for which ones would move money and minds, he considered himself supreme. I was his right hand man, nothing more. Despite which, in certain ways he seemed to rank me above himself. Hourch, he often said, without your diligence this enterprise would fail. There’s no doubt about that. Those were his words. Which Alma seconded, albeit years later, during the hasty sale of the Verlagsanstalt to that Leipzig cabal, long after she had buried husband number two and just before the whole Fatherland went up in flames. Du treuer, treuer Freund, she said more than once, even after she spent most of her riches in the Berlin nightlife and in high fashion houses on the Ku’damm, with that charming Hallodri Dietrich in tow.

I had already been cut from the staff by then, was freelancing and hardly ever saw a paycheck as the publishing house ran out of steam without Hermann. A publishing rule-of-thumb: even the richest backlist can support a lack of forward vision only for so long. And that’s all you’ll hear from Housch – I’ve said my piece.

Reverse of card shown above.

Berlin, 2022

The first sensation of my impending rebirth, a still faint but growing awareness of existence, was a cold touch on my ankles, someone or something gripping me by my feet, and pulling me out of some kind of grey murkiness. Curiously, until those cold hands reached for me, I had completely forgotten I once had had feet, I once had been a living creature, a human being able to touch things, and be touched. In other words, I once had lived, and had so for a span of forty-four odd years, a total of 516 months, or 16,004 days to be precise, leading up to that day in February 1922, when my world went white, then black.

Of the time between then and now, I confess, I have no awareness at all. None. It must’ve been some kind of nothingness. And considering my resistance to being pulled back into the world – kicking and screaming to the degree one can without an actual body – I realize this nothingness must have pleased me.

A hundred years of nothing! And to come back from it. Imagine that! The very thought makes my head spin – hah, I possess a head! – which is now filling up with a torrent of images of the world I knew and the horrors and wonders that succeeded me.

But of this much I’m certain: the void I’m being pulled out of by these industrious heirs of mine, these well-meaning and sincere descendants, lies beyond words – beyond the reach of human thought, imagination or description.

It’s a puzzle really: is a hundred years of nothingness a gap that can be bridged, or does it permanently divide before and after into separate worlds? I’ll bet old Fröbenius would have a thing or two to say about this, if only I could reach him. But knowing Leo, he’s sure to be off somewhere taking his own posthumous victory laps. If he were available, though, he could, and would, wax endlessly on Impermanence vs. Nothingness. He’d lay out multiple highly complicated hypotheses, conveniently ignore the holes in his logic, sneeringly dismiss the objections of others, toss in some ancient tribal myths, and propose a theory so outlandish that no one understands a word of it. But, as usual, we’d all fall over hyperventilating with cheers.

Now despite my initial reluctance to being, at least in a fashion, reborn, I cannot deny what an astonishing spectacle it is to see a life emerging from nothingness, first vaguely cohering from a diffuse and indefinite sea, slowly becoming defined in form, with shapes, outlines and eventually pictures emerging, and finally, life-like moving images, sharper than any one can see on the silver screen. And the whole vision becomes doubly astonishing when it dawns on you that materializing before your eyes is your own life – or what you take it to be.

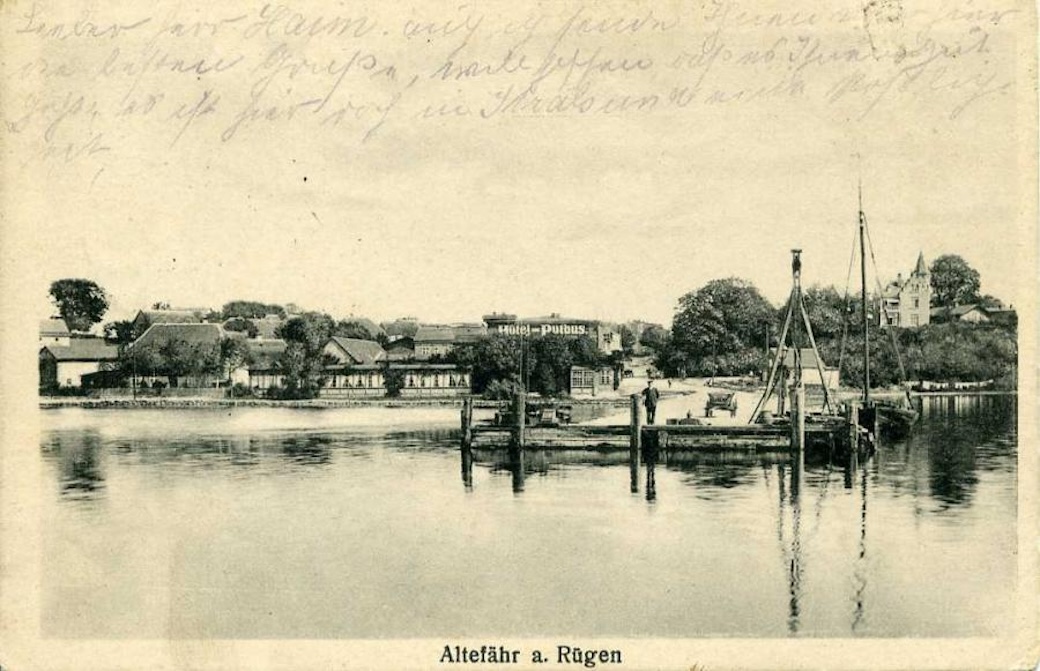

The arrival of the railway (via boat) made Klemm’s hometown a gateway for tourists from Hamburg, Berlin and Leipzig traveling to the popular seaside resorts Sassnitz, Binz, Selin and Gören.

The first images coming back are water, sand, shells on a beach, the sea. And the outline of a distant ferry, carrying – many times a day – a train with three wagons back and forth between our village pier and the magnificent town of Stralsund, the spires of which Papa pointed out to me as I rode high on his shoulders as he walked along the shore. A train on water, he said, was the pinnacle of German engineering. But I was more interested in those who arrived in the trains, the fancy clothes they wore, the unhurried existence they embodied, a life of many wonders I had no comprehension off, but instantly knew I wanted for myself.

When you grow up near the sea, even one as calm and predictable as the narrow straits between the shores of Rügen and Stralsund, a longing for what might be found beyond the horizon, a taste for adventure and the absolute certainty that a marvelous future awaits in distant lands, are somehow placed in your cradle and become your second nature. And that certainly proved true for me.

Papa, on the other hand, was a migrant to the island from the hinterlands of East Pomerania, and as such not plagued with longing for the distant and unknown. Though an outsider with a noticeably different accent, he fancied himself an important man in the village. The images I have of him remain vague, but it seems he was always in uniform, which absolutely had to be spotless and wrinkle-free. Poor Mama. Ah, the stress of every morning presenting Papa with a perfectly ironed uniform and overcoat, should the elements demand the latter. Some say he even wore his uniform to Church. I’m harboring the belief that this, and other unnecessary demands he placed on her were the reason she died so young.

And what about the uniforms I wore, you may ask. You’ve seen pictures of me in them and know I was an Hauptmann at the Maginot Front. Did I feel a certain pride when I wore them? Was I a loyal believer in, and follower of the powers they represented? I cannot say. That memory is hard for me to reconstruct. What I do know, and stand by to this day, is that if I’m put into a uniform, with or without my consent, I will make the best of it. I will seize that opportunity, I will rise through the ranks, I will not be cannon fodder, but a leader of men. And, as I can also unequivocally say, as the memories return, the images of my life crystallize in front me, the exercises on horsebacks, the mud of the Vosges mountains in winter, the smiles and laughter of my lieutenants and my men. But uniforms were not my true love, nor were the barracks or the battlefield. But Alma was. Her and my books – the Verlagsanstalt. And of course Hilde and Ilse were my loves, the pair of them just blossoming in their seventeenth year when things went white, then black for me.

The sleepy town of Altefähr on the island of Rügen, where Klemm was born in 1878 (shown here in 1899).

It was widely said in Rügen that Papa was proud to be the village copper, proud to have been selected by the ominous and far-reaching Prussian bureaucracy, loyal-to-a-fault to his overlords, who, from their residences in far away castles could rely on him to keep the village ship-shape. How good was he at this job? He probably would not have liked to hear this, but as my siblings learned later, most villagers were more impressed with Papa’s ability to wrestle a runaway piglet to the ground than his enforcing of the law.

Not that our village had many law breakers back in the day. But bear in mind, wife beating wasn’t considered an offense then, and the sometimes bloody fistfights over fishing grounds were something the law didn‘t deign to get involved in. Apart from that, there was very little to fight over. But, like every village in Prussia, by Royal decree, Altefähr had to have a village cop, if only to have someone remind the passing wayfarers to move on to the next village when their drinking got out of hand.

The most curious thing about my parents remains that these well meaning and hard-working folk of peasant stock gave life to someone like me. And the mystery, to myself and them, is how I became a man of letters, and a man, I daresay, of refined taste, at least when it comes to books. And proudly so! Nor can I recall, on the other hand Papa and Mama reading, in their too-short years, any book besides the Bible. Except perhaps the church song book, or possibly Die Jahreszeiten an der Küste Pommerns almanac. Of course, Papa relied on his indispensable Landwirthschaft-polizeiliches Handbuch, the chief weapon in his arsenal of authority, probably knowing very well that few in the Village would’ve have been capable of reading for themselves the decrees he handed down out of that volume.

So far as I can remember, my parents did not regularly read the newspaper. Such information as Papa gleaned on events in the world beyond the island came from his conversations in the local pub. There, too, one could often find week-old broadsheets left behind by posh tourists from Berlin, Hamburg and Bremen. Papa brought them home and read the headlines aloud to Mama who mostly sighed – though whether she found onslaught of foreign information depressing, or simply too complicated I never learned. But for my part, as soon as Papa put the papers aside, I leapt on the newspapers – however obsolete – like a hungry kitten presented with a bowl of milk.

Well, we‘ve all heard of merry widows, a much celebrated literary archetype as such, but also not too rare a phenomena in the real world. In fact, word has reached me, now that I’m back, that my very own Alma became a such a celebrated creature not long after my demise. Though I don’t blame her. She was too young, and too rich, and too hungry for love to wear black for very long.

Carnival celebrations at the Klemm House in Grunewald, circa 1925. On the sofa are Alma (right) and her daughters Ilse (left) and Hilde (middle). At the far right is Alma’s second husband, Willy Dietrich, a film poster artist, who died 1932 in a car accident on the Kurfürstendamm.

Which brings me to my next point: merry widows are plentiful and have always been. But a merry orphan? I doubt you can find many in the world of literature, cetainly very few who would be honest enough to admit as much. But I’m here to tell you that whatever you may think of me for saying so, I was one of them.

The images that come up are of a child avoiding his parents as much as possible, sneaking out of the house, burying his nose in any sort of reading matter from the moment he learned his alphabet, engaging in conversations with tourists on the pier. In any case, my mind emancipated itself from my family early. Was it because my parents embarrassed me? Did I see them as simpletons? Certainly neither of them could follow even half of the ideas my overexcited brain produced. I do not really recall how I felt either at, or after, their funerals: first Mama’s and then, two years later, Papa’s. What I can say is how I felt the moment my future was decided upon by my uncle and aunt, that is as soon as I arrived in Bergen – the prosperous town in the center of the island. It was there that I started my apprenticeship as bookseller’s assistant. And the feeling that descended upon, or rather rose up, remained consistantly with me for the next thirty years. It was a sensation of tremendous freedom – of possibility. I was only fourteen, but I was my own man, ruler of my world. A world populated, abundantly and fascinatingly, by books.

Bergen, the largest town on Rügen and site of Klemm’s apprenticeship as a publisher.

To be continued…

* * *

* * *