Marco Polo Mother & Son

by Thoreau Lovell

In the mid-70s I devoured Peter Handke’s memoir A Sorrow Beyond Dreams in which he attempted to understand himself by understanding his recently departed mother. I remember being very moved and disturbed at the time by Handke’s long essay but it receded as a thousand or more other books entered my consciousness over the years. And then, suddenly, last week came Thoreau Lovell’s Marco Polo Mother & Son, a truly remarkable novel about a son in search of his mother and a mother in search of her son. Within moments of finishing it, Handke returned forcefully from the land of forgotten books, not just because of the subject, but because Lovell, like Handke, has written a book just as intense, in which the “action” is mostly in the psyche. And what action abounds in Lovell’s deft presentation of the past as it comes spilling into the present, and the present as an evocation and effect of the past.

Lovell’s subject is hardly unique—I’m thinking most recently (for me) of Colm Tóibín’s stories—but the way his saying gets said is. The dual protagonists, Georgiana, the mother, and George, the son, are given not just equal treatment but equal voices. Georgiana, though dead, narrates alternating chapters with her son. The effect is that of immediacy, due to the first-person narration. Accordingly, we are able, first hand, to see and feel and experience their individual stories while also becoming involved in their respective lives which are totally entangled with one another. Despite each narrative having its own specific focus, each character develops the other so that we have a continual bifurcated point of view.

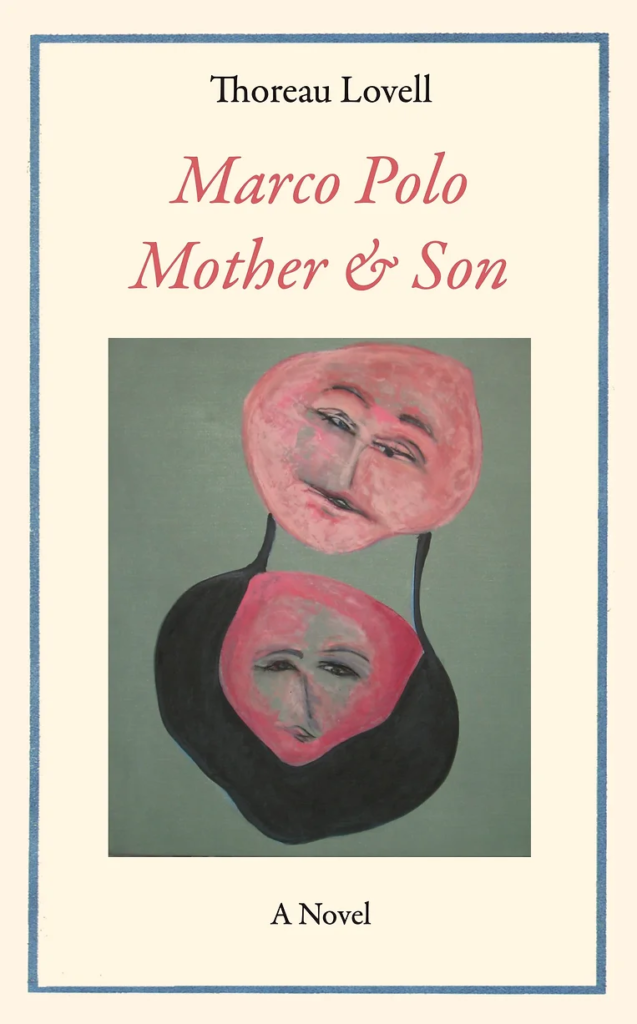

What the characters relate in their individual chapters, however, is quite different. Georgiana tells snippets of her life story; George’s narrative is largely concerned with the final days of his mother, her death, and his attempt to understand his conflicted feelings. While the style of telling is fiction, the book is clearly autobiographical. Lovell even includes grainy black and white family photos in each new chapter heading. The fruit of all this fictionalized lived experience is, of course, the novel itself, which is/was a way for the author to work through his own grief and actions before and after his own mother’s death.

Indeed, the psychological underpinning of George’s chapters is his relentless questioning of his actions in light of his mother’s illness and progression to the other side. Outwardly, he informs us of his very settled life in Berkeley with his wife Paula and their daughter Lily. He comments on the difference between his present life and growing up in Fresno: “The contrast between life there and life in Berkeley was stark and unsettling. Fresno felt like the urban equivalent of a disposable advertising supplement. While Berkeley felt like an oasis where high quality versions of everything you’d ever want for yourself or for your family could be found not more than a couple of miles away.”

But as his mother sickens and then succumbs, he becomes obsessed with what he could have done better to keep her alive. “She died two days before her 84th birthday,” George tells his friend. He then reflects: “…I realize I’ve been repeating that phrase two days before her 84th birthday to anyone who asked. To make it clear that she had lived a long life. And that I had provided in every possible way for her care. And that I had not subtracted a single day from her life through neglect or selfishness.”

While George’s chapters mostly look inward, Georgiana seems eager to sketch her life from early adulthood onward. She devotes much attention to her 20s, maybe, because as she tells us, “The older I got the unhappier I became with what I remembered.” What we do learn from Georgiana is that she was originally from Detroit but moved first to San Antonio and then, at the behest of her Uncle Bill, to Pasadena. She chronicles bits and pieces of her life in coastal California, including meeting Whitey, the man who will become George’s father. We quickly learn—but only from Georgianna, not George—that Whitey is an ex-con and a hustler and a writer. Or as she tells George from beyond the grave: “He was a good man and a good dad and a good writer but he was a terrible husband-writer-dad. He couldn’t do it all. Not even close.”

Georgiana doesn’t leave Whitey, however. When George is young, Whitey dies from a heart attack on the side of the road. She remarries and moves from the California coast to Fresno, “a dry valley turned into a farmer’s paradise.”

Perhaps because he lost his father at a young age, George never reflects on him nor on his stepfather who remains nameless. His sole focus is on his mother. And yet his mother, isn’t quite sure of who her son is or what his intentions truly are: “Oh, my inscrutable son. You never know your children any better than they know you.”

From the beyond she writes:

Now I wonder whether I even have a mind for memories to appear in. No mind, no body, no time, but there is something like awareness. I’m aware that I’m here and not there. I’m aware that my son George is wandering through his memories trying to create something like a memorial for me.

I’d like to help him, but he seems to enjoy doing it all by himself.

Overdoing it, is more like it.

He’s trying to write a requiem when a simple pop song would do the trick. More power to him! Whatever that old saying means.

Dwelling on the meaning of words spirals me away from any sense of George or anyone else I ever knew. So, I step lightly, mindful that remembering is like putting on a play or projecting a movie into a dark room.

For his part, George continues to muddle through, never quite realizing him ambitions, never quite coming to terms with being the son of his mother. In the final chapter George narrates, he tells us this while looking out at the Pacific:

Out of habit, I looked for my mother. I didn’t really expect to see her, or hear her, or sense her. But for some reason I kept looking. Maybe, I decided, it was finally time for me to accept my little slice of reality for what it was. Severely limited to the here and now. Locked in its three-dimensional predictability. A narrow tunnel burrowing straight through time without any funny business….No matter what happens with this book, I realized walking back to my car, it will always be a poor substitute for the tree I didn’t plant, the memorial I didn’t give, the obituary I didn’t write.

This is George talking, not Thoreau Lovell. The tree, the memorial, the obituary is Marco Polo Mother & Son.

—Review by Christopher Sawyer-Lauçanno

***