by Christopher Sawyer-Lauçanno

Chapter 49: I Become Expelled

As I repeatedly told Sr. Daimler and others who decided they needed to pass judgment on me, “It was all just a spontaneous, silly stunt. I meant no offense to the Church.” Somehow, they did not seem to believe that I had much credibility. The Latin teacher, a stern, humorless Jesuit, just kept shaking his head, scowling in disapproval. I did not say that I thoroughly enjoyed my prank, and that most of my schoolmates did, too. I did not say I was repentant, only that I had made a mistake in judgment. Perhaps I should have been more disingenuous, begged forgiveness, confessed to the enormous error of my ways. But I couldn’t. I was smiling inside and couldn’t help it.

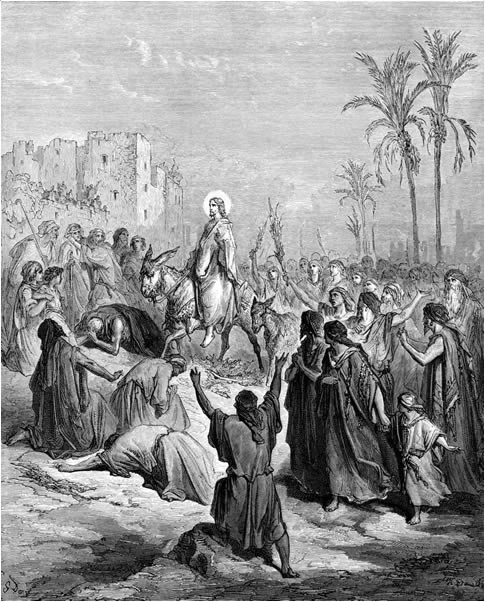

The event that precipitated my dismissal from the Colegio was, as I said, genuinely serendipitous. Had the stray donkey not wandered up in front of the school, and had a palm tree not been sheltering the walk with its low-bowing leaves, nothing would have happened. The combination of burro and palm leaf, however, seemed at the time, rather obvious. The unseasonably warm early December day may also have contributed to my undertaking.

My plan did not arrive in stages but all at once. Its execution, however, was quite methodical. Without saying why, I asked Luis to give me a lift so I could hack off a browning palm leaf with my trusty pocket knife. It wasn’t easy. I pulled and twisted and stabbed and sawed at it for several minutes before the frond decided it could release itself from its trunk.

Miguel looked on curiously as he held the burro by its halter. It was evident to us all, including the small crowd of classmates that had gathered before the gates of the school, that we should hold the donkey until its owner could retrieve it, or at the very least, tether it to the wrought-iron fence. I thought so, too, but had a variation on the theme in my mind.

I handed the palm branch to Luis, then walked over to the waiting burro and carefully mounted her. She didn’t seem to mind. Indeed, she was quite complacent with having a rider on her back. I took the reins and beckoned Luis to hand me the palm. Giggles began almost immediately, and while we were months away from Palm Sunday, it was already clear what I was going to do.

I gave the burro a nudge with my knees and she slowly began moving forward. I waved the palm. “Vengo en son de paz,” I chanted as I moved toward the gates. “Vengo en son de paz.” My classmates followed along, some in front, some flanking the donkey, and a few in front. Jaime, with a bow and an extravagant hand gesture, welcomed me into the courtyard. Someone shouted out “Bienvenido. Ven en paz.” Others quickly took up the cry.

I had not gotten too far into the courtyard before Sr. Daimler came bursting through the inner doors. I decided it was probably time to dismount. I dropped the palm frond. My welcomers dispersed to the edges of the courtyard, except for Jaime, who grabbed the halter reins to steady the burro as I descended.

Jaime spoke first. “Cristóbal wanted to make sure the burro was safe,” he said. “We found it on the street.”

Daimler, so far, had not said anything, just stood, arms akimbo, mouth open, as if he were silently screaming. By now a couple of other teachers had emerged, including the old Jesuit.

“Cristóbal. Mi oficina. AHORA.”

I walked slowly behind, then suddenly heard a few voices say loudly in near unison: “Vete en paz.” Daimler turned. All were silent. I tried to conceal a smile. Daimler saw it. He frowned deeply, then motioned me to go ahead of him.

Had we not been a few months behind in paying the school bill, I doubt I would have been expelled. Suspended for a few days, perhaps, but not kicked out for good. I know Mr. Wright tried to save me but the fat Jesuit didn’t, even though, I was at the top of his Latin class. Daimler never particularly liked me, nor did his wife. The other teachers were mainly indifferent. And so, on the 12th of December I ceased to be a student at El Colegio Americano de Durango.

Chapter 50: I Become Forced to Leave Mexico

I was somewhat surprised that neither my mother nor Ray did much to support me at school. My mother did go to talk with Daimler but left after only a few minutes. When I asked her what he said, she only replied that he wanted her to pay the bill, and that the decision to kick me out was irrevocable.

There was another good secondary/prep school in Durango, and I told my mother and Ray that I wanted to go there when the term began in January. They were both rather non-committal. It was then I realized that the jig was up.

For me, December has always been crueller than April. The December of 1965–the month we moved back to El Paso–was one of the cruellest months of all.

The announcement came appropriately on a chilly, drizzly day a couple of weeks before Christmas, and had nothing to do with my schoolboy antic. Had I not been so focused on myself, 1 should have expected it. Our financial situation had gotten to an impossible point, My uncle and Smitty, had finally pulled out as our bankrollers in the early fall, when my uncle, finally almost broke, was fired from his job at the phone company for excessive absences. Other investors teased us about coming in, but none had. Consequently, not even the payroll at the mine, let alone our expenses, were being met by the trickle of mercury that the somewhat-repaired, but hardly-functional kiln, was able to produce. Ray needed another operation desperately—he was still unable to walk on his own—and had been told that he should not put off further surgery. He decided it made the most sense to go to a Veterans Hospital in the States since we couldn’t afford Dr. Rodarte. Had it not been for Ray’s mother dipping into her savings to support us, we would probably have had to leave even sooner, and I would have missed out on performing my grand entrance.

I can’t remember exactly how the announcement came, or who announced it; I recall only that the outside gloom had drifted inside the house, and that when I walked into the dining room from our patio, I sensed that something was terribly wrong. Ray and my mother were seated in silence at the long plywood table. Lunch was ready. I ate, attempting to make perfunctory conversation, but neither of my parents spoke more than a few words. Then, suddenly, I was informed that my life again was going to change forever. And soon: in four days, providing I could negotiate a reasonable fee for a cab driver with a station wagon to take us to Ciudad Juárez.

I sat quietly for a moment, beyond sad, numb I suppose. Then, reviving a little, I asked if there was any way I could stay, at least until the end of the school year, if I could get enrolled in Colegio Juárez.

“Luis and Jaime have lots of extra rooms. I could probably board with them.”

“That’s a good idea,” my mother said, “but we can’t pay the school bill. Right now, even mercado eggs are a stretch.”

“It’s Ok,” I said, with as much nonchalance as I could muster. “I’ll talk to the taxi drivers, see what I can arrange.”

“Play them off against each other,” said Ray. “Don’t just ask one, and say OK.”

I was angered now, and replied testily, “1’ll get the best price I can. Christ, I’ve been doing everything for the last ten months and you’re now trying to tell me how to cheat a cab driver.”

“Put the quote in writing and have the driver sign it,” said Ray, unmoved by my outburst.

“Got it,” I said.

Despite the rain (the drizzle had escalated) I walked into town slowly. By the time I neared the taxi queue, I was soaked to my underwear. I took shelter under a large public entranceway, then ducked into the Hotel Casablanca and made my way to the bar. I sat at a small table for a long while, sipping a mineral water, staring out at the street. I was trying, I suppose, to memorize Durango, not just the boring scene in front of me, but all that had happened to me in the last years, trying to put some perspective on who I had become since my arrival. Then, seized by a desire to communicate my despair to the world, I began to write a letter. First, I wrote a long missive to Mr. Wright, then, a shorter one to Luis and Jaime. I felt an acute need for some sort of closure.

It was six and dark by the time I reached the taxi stand outside the Casablanca. I walked up and down the line getting quotes, all which, to my way of thinking, were fairly high, and all within about 20 pesos of one another. I walked back up the line, trying to get a better price, but to no avail. Every time a new cab would join the queue, I’d inquire of the driver. Finally, on the verge of resignation–I think the lowest quote was 2000 pesos ($160), another driver, with a station wagon, joined the rank. This time I simply asked whether he’d be willing to drive me and my family to Juárez on Saturday for a thousand pesos. He looked down, then up in the air. “1200 pesos,” he said. I took out my pen, wrote down on a scrap of paper $1200 and what it was for, and had him sign it. I told him I’d check back with him on Friday afternoon.

The next few days were hectic. I arranged for all of our furniture and appliances to be sold to a dealer. Unfortunately, he arrived on Thursday morning instead of Friday. When I returned to the house for siesta break after running some errands, only a few odds and ends remained. We embarked on a furious packing spree. César and Mariaelena sensed the tension; César decided to hide in the closet, my little sister wanted to be in her mom’s arms. And I don’t remember helping much, just deliberating whether I should pack my school uniforms. What I do recall is that it felt odd that all of our worldly possessions could fit into five or six duffel bags. We checked into the Casablanca late that night.

The next morning, I wired most of the money received from the furniture sale to Javier and posted a letter to him from Ray. The missive informed him in some detail of the situation, and advised him to sell all the belongings and equipment left in Sain Alto, and after paying the miners, to keep whatever cash remained. I also mailed my letters to Wright and to Jaime and Luis.

My last day in Durango should be vividly deposited in my brain, but curiously I can’t remember it at all. I probably was in a daze most of the day. Nor do I recall much about the trip north, save that we left about 7:00 in the morning and drove straight through, arriving late that evening in Juárez where we put up in a hotel. The next morning, Ray’s uncle came and fetched us. By 10:00 a.m. we were back in El Paso.

Chapter 51: I Become an Alienated Resident of El Paso

After a few cramped weeks in Ray’s mother’s tiny one-bedroom apartment, we moved into a house on Rio Grande Street, furnished rather sparsely with cast-offs from Ray’s relatives. It wasn’t much of a place, but as least I had my own bedroom. Ray. meanwhile, though hardly mobile and in pain so great and so constant that even his many daily shots of tequila couldn’t completely efface it, got work in his fallback profession, as a printer at the El Paso Times. He had decided to work for a few months before entering the V.A. hospital for his foot operation. My mother found a job at a steel company as a secretary. César And Mariaelena were enrolled in a nursery school. I picked them up each weekday and brought them home. I too started working several evenings a week washing dishes at restaurant. I hated it, but I could keep the dollar an hour I made, not for frills, but to buy my school lunches and clothes and everything else I needed for my individual survival.

For at least the first couple of months after our return 1 was in rasher deep depression, as I’m sure, were my mother and Ray, but I was too preoccupied with ay own personal despair to pay much attention to theirs. Not, do I recall, were they terribly sympathetic toward my plight. I sought some distraction from the grind by reconnecting with my school acquaintances from before, but I quickly realized that I couldn’t really confide my true feelings in them. Consequently, I ended up, more often than not, feeling distinctly alienated from then and from their petty concerns.

Since we had arrived a week or so before Christmas 1 was allowed to wait until after she holidays so reenter El Paso High. Somehow, with only my final report card from Durango from the year before, and without a current transcript, I bamboozled my way back in. I got signed up for more or less the same courses I’d been taking–English, geometry, French, chemistry but in place of Mexican History, Latin and Spanish Literature, I was enrolled in physical education, U.S. History and journalism.

Except for journalism, where I was immediately put on the school paper, I hated most of my courses at school. Compared to the Colegio, the classes seemed gigantic, the expectations low, the teachers bored and boring, the subjects vastly watered-down equivalents of what I was being taught in Durango. In English, we spent weeks reading Deerslayer and a few of the usual old short story chestnuts. U.S. History, of which 1 made up the first half of the year in two weeks, was taught by the football coach. The pace was tortoise-like. We watched movies most of the time.

French, too, was awful. The teacher, a cutesy, Texan blonde, spoke the language with an abominable accent. After the third week, I tried unsuccessfully to get a transfer to a higher-level class, but because of scheduling difficulties, couldn’t manage it. Chemistry, if taught uninterestingly, wasn’t bad, but geometry was excruciating. The teacher, an ex-military man with a crewcut, spent more of his time watching for rules infractions than teaching. Any male student caught breaking some trivial rule—talking to a neighbor, not paying rapt attention, slouching in his seat, chewing gun, “spicking Spinach,” not answering a question with a “Sir” tacked onto the end of each declaration–was immediately led outside to receive somewhere between two and five swats from the teacher’s paddle. I was a victim at least once a week, usually for failing to offer proper respect to Mr. Baker.

The yacht Granma, that transported Fidel and 83 other revolutionaries from Tuxpan, Veracruz, Mexico to the shores of Cuba.

Chapter 52: I Become a Pinko

I think I became a “commie sympathizer” by accident (osmosis is perhaps an apter description), because 1 have no memory of having decided one day that Fidel and Che were right and the U.S. wrong. I think what happened was that during the time I spent in Mexico, when I was beginning to develop a political consciousness. I picked up ways of thinking about current events that were distinctly different from the positions Americans were told by our government to hold. That is to say, free in Mexico from the predominant North American view of things, I developed a different perspective on global events. Indeed, when discussing the Dominican invasion with friends in the States, I was shocked to discover that they in no way shared my view, or that of many Latin Americans, that the rape and pillaging of Santo Domingo by U.S. forces was a Yanqui power play designed to show the rest of the benighted hemisphere that Uncle Sam still believed mightily in manifest destiny.

My mother, influenced more by my grandfather’s strident socialism, than by much consciousness derived from living in Mexico, was sympathetic toward my positions, but thought me a bit rabid. Ray, a capitalist republican, on the other hand, thought I had become a dangerous pinko. My friends were mostly apolitical, with the notable exception of my old acquaintance Jaime Castro, with whom I became hanging out a great deal during the hot summer of 1966.

For some reason, Jaime didn’t realize that Mexico had harbored Fidel, and that the Granma, the boat that carried Fidel, Che, Raul, Cienfuegos and some 80 other comrades, had sailed from Veracruz to Playa Las Coloradas in Cuba. Jaime really liked that, as his family was from Veracruz. This made him even more convinced that he was a cousin to Fidel. I doubt he was but the only facts we paid much attention to came direct from Cuba.

It was Jaime who introduced me to Radio Habana. Almost every Saturday night after work we’d hang out on his flat roof, where he’d built a little open-air cabana with a thatched roof. At eight o’clock the military band music would crackle, fade in an out, and then RADIO HABANA CUBA in capital letters would burst, with accompanying static, through the shortwave’s little speaker, and Fidel would come on and talk for a long time about the crops and the capitalists and the comrades.

From the reporters in Habana we learned all about the sugar harvest, cigar production, collectivism, free universal health care and education, equal opportunity for all. Also about how revolutionaries in other parts of the Americas, inspired by the valiant examples of Fidel and Che in the Sierra Maestra, were making great strides in toppling U.S. puppet regimes. And also about a little war the United States was conducting in Southeast Asia that was only beginning to be news on the nightly North American newscasts, but even when reported, was related from a perspective distinctly skewed from what Radio Habana told us.

Best of all, though, was when Fidel addressed us directly, his voice strong, measured, and seductive, his well-turned rhetoric swelling with socialist passion and conviction. He talked a lot about his hopes and dreams for Cuba, about the need for everyone to participate in the glorious struggle, about the dangers to the Cuban people, indeed to all people, of the CIA and the U.S. military industrial complex whose only interest was in fattening its already bloated body on the bodies and minds and souls of the masses: “Remember the Bay of Pigs.” “Remember Caamano.” “Remember Arbenz.” “Viva Fidel.” “Viva Cuba Libre.”

Jaime gave me my first cigar, a big Cuban Romeo y Julieta that he bought in Juárez. We smoked them while listening to Fidel whose speech outlasted the cigar. It seemed another way of communing with Cuba and got us talking about palm trees and beaches and beautiful women in bikinis, and then when Fidel got really wound up and wound us up, about volunteering to cut sugarcane next summer when we got out of school.

***