The Vanished Publisher I

Tobias Meinecke & Eric Darton

Berlin, November 2022

If you ask them, and even if you don’t, they will tell you all sorts of things about me. Some true. Some not so true. Some blatantly false. Some scandalous. Some praising my virtues, real and imagined. And all so opinionated — this small herd of specialized and, may I add, occasionally arrogant scholars and antique book sellers, who may or may not be as well-versed in the history of German publishing, much less the legacy of Verlagsanstalt Hermann Klemm AG, as they claim to be.

But can you imagine? Now another, more innocent pair of “literary detectives” has started poking into my life, my lore, my legend, and my documents. Indeed, these two enterprising fellows are none other than my great-grandsons T. and B.; the first springs from the lineage of Hilde, and the other of Ilse, my daughters.

What are these curious cousins up to? And why their sudden interest right now? Well, I suspect it dawned on one, or both, of them that 2022 was the centenary of great grand-dad Hermann’s passing – a hundred years since nature forced me to take leave of this world. Which occurred under circumstances far more disagreeable, indeed painful and shocking, than kindly Kurt Wolff and good old Hourch made it seem. No, I don’t have to tell anyone that dying is a messy business. For me, the most distressing part was seeing Alma so devastated. Oh yes, I know she rebounded nicely with Dietrich, and that did console me. After all, if one is not an entirely cold fish, one wants one’s widow to be happy.

I certainly didn’t want to go, believe me. And not least because those early twenties were a time you wouldn’t want to miss. Everything was racing ahead at full speed: industry, society, politics – the world, and particularly Berlin, was up for grabs. Anything that could happen did. And make no mistake, publishing meant power in those times, more so even than armies and armaments. Wherever you looked, new techniques and markets opened up right and left. No one in their right mind would’ve voluntarily left the table. At the Verlagsanstalt we were on fire, churning out bestseller after bestseller as if there was no tomorrow. Which for me there wasn’t — banished from the game at forty-four — still full of ideas and vital energies! I am not being immodest when I say it was a loss — not just to literature, but to Germany — to culture! And not just a loss — a tragedy!

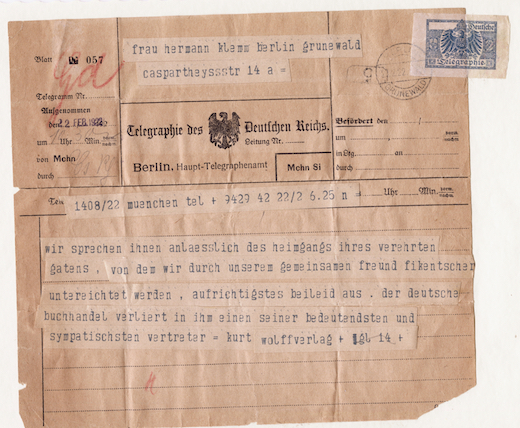

”In him, the German publishing industry loses one of its most important and sympathetic representatives.” Kurt Wolff (1887-1963), the giant of literary publishing during the Weimar Republic, expressing via cable his condolences to Klemm’s widow Alma Klemm, née Beer about the untimely death of his colleague and competitor. Wolff was a risk taking publisher, known for providing a home for such diverse and important authors as Heinrich Mann, Franz Kafka, Gottfried Benn, Georg Trakl, Franz Werfel and others. Barely escaping the Nazis, Wolff founded Pantheon Books in New York in 1942 before retiring to Switzerland after the war.

It is heart-warming to learn that, of all people, Kurt Wolff agreed with me on that, the tragedy part. Who would’ve thought? The Wolff: lover of the obscure, the oddball, the barely comprehensible – he who despised popular books, ran away from them like they had the plague and proselytized against them like someone converting the Philistines. His not only having kind words for me, but sending them by cable? I would’ve been more than surprised, and pleased, back then if I had known about that. This is the man who put that incestuous Austrian hysteric Trakl on his pedestal, not to mention Kokokschka. Kokokoshka! In full color. Madness. Kafka, you say? Nobody could’ve seen Kafka becoming Kafka. But Wolff did – I concede him that.

Ah, but old Kurt was probably also a bit sentimental about the laughs we shared, the drinks and good meals, in Leipzig. I mean, very few could converse like him — yours truly excepted.

Still, I confess, this flurry of sudden attention comes as a surprise — and it strikes me as ironic to say the least. Imagine yourself being suddenly awakened from a deep sleep. Which is not to say that I don’t enjoy being celebrated and praised. Nor would I miss a great party, be it in my honor or not. On that last point, my Alma was a party-girl; she and I — on that we were always in agreement — would never let a festive opportunity go to waste.

Indeed, truth to tell, I’m flattered by the attention, however long my recognition was in coming. And I cannot help but think that had fate dealt me a different hand: a childhood less deprived, a not-so-serious heart condition brought home from the war; had certain medical techniques been invented but a few years earlier — why my great-grandsons, instead of struggling to write me into the history books, would be sitting where the heirs to Rowohlt, Fischer, Suhrkamp, Kiepenheuer, Piper, Ullstein and so forth are today, sunning themselves on a terrace in Cap d’Antibes, collecting cozy dividends year-by-year, and letting others do the hard work of making and selling books.

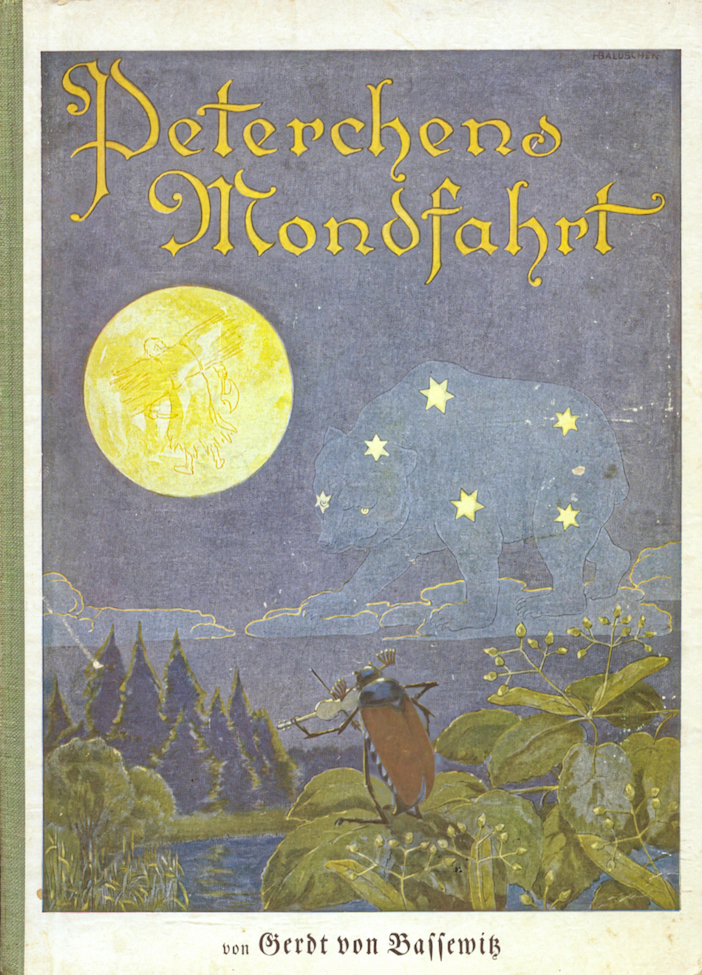

Now as for Ernst Rowohlt, from what I heard, he claims to be the last to have seen von Bassewitz alive, a tale which — if Rowohlt hadn’t proven over and over to be utterly unreliable, not to mention a shameless drunk — I might be inclined to believe. And why? Simply because even if Rowohlt had been sober at that moment, he’d never have found the right words to keep Gerdt from doing himself in. If anything the opposite. Were I in the process of abandoning all hope, Rowohlt is the last man I’d want to have trying to cheer me up. But I’m digressing when what I really want to say is that, in my experience, empathy is not a well developed muscle in publishers. Especially when alcohol is your main source of nutrition and, moreover, you’re trying to smooth things out with an author who dumped you for your competition. Do you think I’m being hard on my fellow publishers? No, merely truthful – we’ve never been a gentle tribe. Indeed, if anyone needs further proof of how callously we can think, consider this: Von Bassewitz’s rush to poison himself brought Alma and the twins quite a windfall on Peterchen’s Mondfahrt sales. The man apparently had no heirs, and if he did, they’d no idea what the word royalties meant. Which made me eternally happy. Or happy in eternity, more precisely, since I was already well across the Styx before von Bassewitz came chasing after me.

Peterchen’s Mondfahrt, Gerdt von Bassewitz classic German children’s book, still in print today, was first presented as a theater play in 1912, before being issued as a book, illustrated by Hans Baluschek, by Verlagsanstalt Hermann Klemm AG in 1915 – instantly becoming one of the publishing houses bestsellers and cash cows. The book was followed by three film adaptations and five radio-plays.

Speaking of Hades. I want to tell you something which may not be good news to the living concerning their own prospects: I’m all alone here. There isn’t anyone in this place but me, or anything you could describe as an object. In fact, there is not a book to be found anywhere – and certainly not one by Gerdt von Bassewitz.

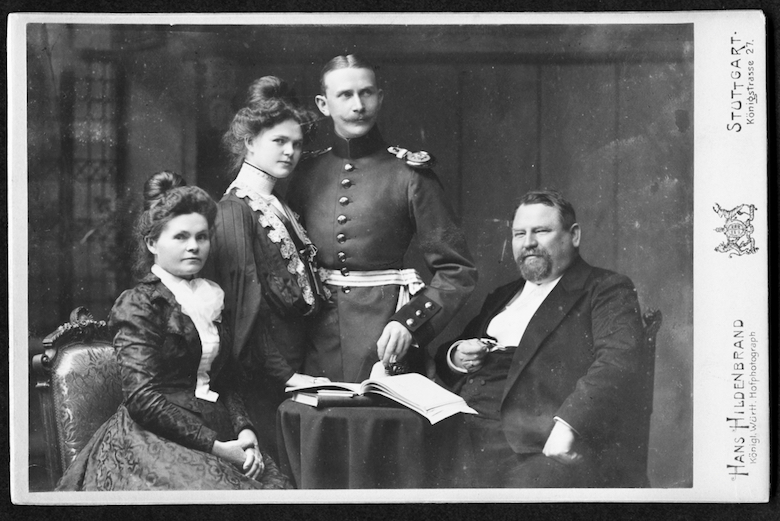

But I’ve strayed from the matters on hand: my metaphorical unearthing and resurrection. I might as well be honest and say that a good deal of my unease with my well-meaning descendants poking into my life stems from the fear that their deep dives are based on a falsely premised family legend: Hermann Klemm, war hero. In gilded frames on mantlepieces and photo albums collecting dust in attics across Europe, the image of me kept alive by my successors is that of a Prussian officer wearing a Wilhelminian mustache. Proud. Stern. Though high on my horse, I appear slightly bemused. Other images also show me in uniform with my young, vivacious bride in my arms. Or as a battalion commander beloved by my troops. In short, I am depicted as a militaristic relic from a bygone, irrelevant era. A man of yesterday.

Family photo of Hermann Klemm and Alma Beer, on the occasion of Klemm becoming a Lieutenant of the Reserve in the Imperial German Army. From left: Alma Beer née Schwarz, Alma Klemm née Beer, Hermann Klemm, Heinrich Beer. Rastatt, Germany, 1902.

How misleading these images are. As if the military shaped my life, made me who I was! I tell you, it did not. Counting the length of my entire service, I spent fewer than four of my twenty-five adult years in uniform. And if the Great War hadn’t pulled us all into its maelstrom, it would have been much less. Though I certainly felt a duty to my Fatherland and an obligation to serve it in a righteous cause. But within a year after the hostilities began, the senselessness of the effort became overwhelmingly obvious, and my wounding at Hartmannsweiler Kopf — despite the permanent damage to my heart and constant worry over the men I felt I had abandoned — came as a welcome reprieve.

The truth is that the direct hit on our position gave me what I needed most: the opportunity to return to all that which I missed: Alma, my desk, my books. So, no — the military did not make me who I was. My youth in Rügen did. Coming up the hard way. And publishing, of course. My books, my Alma, yes, and Hilde and Ilse, too.

”Alma and Her Daughters.” From left: The twins Ilse and Hilde, Alma. Stuttgart, Germany, 1905.

One thing my enterprising great-grandsons will soon discover in their poking around, is that old man Hermann and company attended the first Book Fair to be held in Frankfurt after the Armistice. It was in October 1921, and I brought not only our latest publications and the best of what was left of our backlist, but also the Big Book.

Yes. That one. My still unfinished, constantly shifting dream project, caught in the turmoil of its time, in the works for close to five years, ever-expanding, and still, that October of the Fair, without a definite publishing date. It’s hard to speak about it now without deep feelings of regret and wishes for second chances. But in the fall of 1921 we had reason to hope.

I’d brought Hourch and Kupsch along to Frankfurt, at a significant extra expense. Alma stayed in Berlin with the girls — they were still in school — ah, but you should have seen 16 year old Hilde, practically begging to come along.

Hilde, so eager to follow in the footsteps of her father – my God.

Hourch, I almost had to force to come along. He had no patience for the big-name publishers with their intellectual and bourgeois pretensions, talking with a quiet, and entirely fake authority — as if they were Proust or Raabe themselves. Most of them, I assure were quite capable of gushing volumes of praise for themselves, but developed a curious writer’s block when it came to signing checks to their authors. “We sell printed and bound paper in eye-catching covers!” — that’s what Hourch always said to me. The rest, he maintained, is the work of the authors. And I didn’t disagree. Certainly I knew, better than most, how and where and when to make the most of their talents — to their glory and my profit. But I never lost sight of who it was that made the bounty possible.

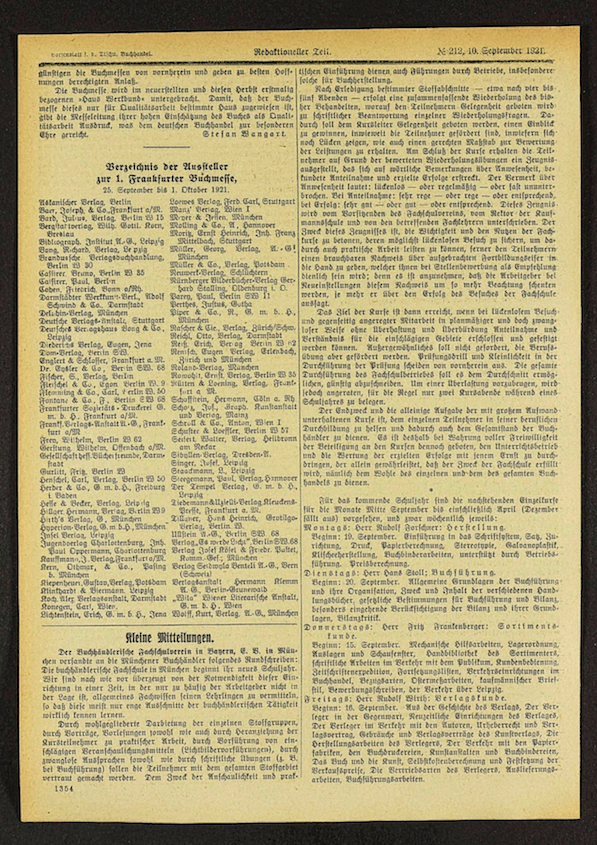

”First Frankfurt Book Fair 1921.” Listing of participating publishers in the trade publication BÖRSENBLATT DES DEUTSCHEN BUCHHANDELS, Issue 212 / 1921. Participants still active today: DVA, Fischer, Herder, Hyperion, Insel, Kiepenheuer, Piper, Rowohl, Ullstein.

Now before we left for Frankfurt, I made sure old Kupsch packed and polished all the medals, and dusted-off all those awards from the 1910 World Fair. Only ten years but it seems like – and was – another world. I selected the finest volumes in backlist for the display: leather-bound, numbered and signed first editions, by, why not say it? the foremost writers of the day.

Hourch and Kupsch preceded me to Frankfurt and set it all up. It’s funny, and perhaps this is a consequence of being dead, that I don’t remember whether I was filled with anticipation or dread when the day came to travel South. What I do recall is how much I was looking forward to having dinner with Leo Frobenius on the night of my arrival. He’d telegraphed to say he had revisions for the Big Book that he wanted to discuss. The changes to the text would reflect the new mood and sentiment in the Fatherland and would, he said, make it a huge success, and the crowning moment for HKV. Though I knew the mere scale of the enterprise would prevent that, I confess I was all eagerness to see what he proposed. To my surprise and frustration, during dinner he scarcely mentioned it and instead regaled me with colorful accounts of his most recent exploits in Africa, to which, I confess, I listened with only half an ear. Oh, and I must accompany him on his next expedition? [Heaven forbid!] And could I connect him with Herr so-and-so… ? [With pleasure, but without guarantees!] Etcetera, etcetera.

And where, he wanted to know, was our very own Joseph Conrad? Why had this Pole landed in England, not the Fatherland? Why is he writing his masterpieces in English, not German. Well, they had treated him better in England than Hamburg – no surprises there!

Those who know me will attest that it’s a rare thing to find me reduced to passively listening. But that evening, with Frobenius, there was nothing for it; the man was a waterfall.

When I finally pried myself out of his clutches, I went straight to my room to read his revisions. In truth, the text was only marginally different from the 1917 version: the same exoticism, the eternal grievances against our betrayers — still fascinating, yes, and perhaps even accurate to some degree. But I read and read again, finding no fresh insights as promised, and realizing that expanding the book to a gargantuan scale was hardly worth the extra expense. What was he thinking, trying to pull one over on me? Never mind the Fatherland, I felt betrayed. For a moment I considered calling his room and giving him a piece of my mind. But at the Verlagsanstalt we had already agreed that it was the artwork that would make or break this book. It was on those paintings, those magnificent portraits and their most faithful reproduction that we had to put our money. So I shrugged it off — to hell with the text. And I told him next morning at breakfast: I will publish the deluxe folio of Die Gegner Deutschlands im Weltkriege, but only if one of two conditions pertain: either we sign five hundred orders at the Fair, or we find a partner to cover our probable losses. He didn’t like it, but what was his choice?

And to think, when it came to the Frankfurt Fair, I almost didn’t throw my hat into the ring –- too many third-rate publishers wanting to rub shoulders with the big names, muddying the waters. Add to that the time and expense of traveling, accommodations for three, and shipping so much stock from the Berlin warehouse. But in the end, something pushed me off the fence. Was it a premonition of something to do with business, but a business spiced with, well, one can only say it: pleasure. Or at least stimulation of a rare variety.

Hah! And the pokers into Old Man Hermann will be a long time discovering what I’ll tell you now, for of this there are no records but my memory. Now, how to describe the youthful, but not-so young woman? Slender, in dark tweed and wearing a hat with a veil — highly unusual for the day — something out of another time, from before the War. And blue-green eyes of so unforgettable a color, I swore I must have seen them before.

I didn’t see her enter our stall, but Hourch told me she came on the morning of the fair’s last day, around eleven. And here’s the wonder of it: she stayed until fifteen-thirty, going through every book on the tables, systematically, one after the other, like an archaeologist! Sometimes she’d glance at one, then put it aside. Others she would page through slowly as though reading with great concentration. Or she would get, for half an hour, completely absorbed in a single color plate.

It was long past noon when Hourch called me from the back, and I introduced myself to her. She smiled and shook my hand, but didn’t volunteer her name. Nor did she seem interested in conversation. She only had eyes for the books: my books. And as we had a great many customers that day, it was only rarely that I could glance over at her. But whenever I did, there she was, making her through the entire stock from left to right and not even taking time for lunch. And then, she called me over. “Herr Klemm,” she said. “I wish to buy a copy of every book you have here.” Of course, I didn’t betray my astonishment. “Certainly,” I said, as though this was the most normal thing in the world. “But please,” I said, “allow me to cover the cost of the shipping. To where — ?” But she thanked me for my generosity which would indeed be unnecessary. For she wished to take them all on the train with her — imagine that, nearly thirty volumes!

Well, I don’t know what possessed me, but as she was writing the check, I offered her a cup of tea and biscuits. She looked at me with those astonishing eyes, until I, a man who does not blush easily, began to feel my knees shaking. Then, with a curious half-smile, she accepted.

We sat in the back of our stall, separated by the little folding table on which Kupsch had set the tray and to my continued embarrassment, I found myself, quite at a loss to make conversation. Nor did she venture anything on her account, but rather sipped her tea with an entirely unaffected delicacy. In a kind of desperation, I turned toward the entry, as though wishing to check for customers, and my eye lit on the black portfolio. Not any portfolio, but the one containing the first color proofs of those portraits we commissioned for the Big Book in the waning months of the War. Would Madame care to see them? She would be most interested.

As I untied the binding, she fixed me again with those eyes

”You’ve come a long way, Herr Klemm.”

“A long way from where?“ I almost replied, but thought the better of it.

“I have been blessed with success, Madame, if that is what you mean.“

”You don’t know who I am, do you?” she asked.

Ohne Mode – 20 weibliche Aktstudien nach der Natur. Portfolio of 20 Nudes by W.Hümmer, Munich. Art prints in folder. Kunstverlag Klemm+Beckmann, Stuttgart, 1902.

* * *