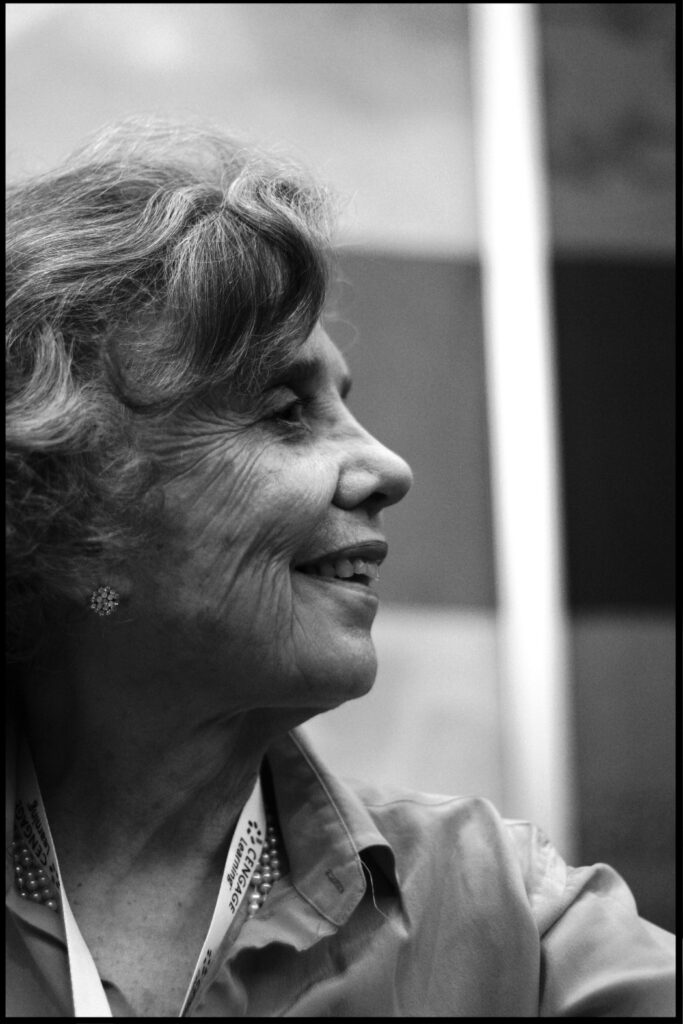

La Sobreviviente

A woman of letters is a survivor. She survives a childhood full of discouragement for the solitude it takes to write. She survives partnership, children, and bosses, all of whom bear society’s encoded demand: Prioritize caregiving and squeeze the writing in. Even when she starts to emerge in middle age, wriggling from the cocoon of social norms, the only ones that notice and sustain her are the other limping, gray butterflies.

Elena Poniatowska survived. She persevered through a girlhood where her writer’s curiosity was always suspect, an experience she described in her early novella, Lilus Kikus. She was a wife, a mother to three children, and a sister to a brother killed in a 1968 massacre of protestors in México City. She kept writing—including a book on the massacre, La noche de Tlatelolco.

As journalist, she published a mountain of interviews, analyses, and critiques. She developed a unique, diary-like style of reportage—“las cronicas”—that was fully realized in her book on the 1985 México City earthquake, Nada, nadie: las voces del temblor. She racked up 40 books of fiction and nonfiction. Yet contemporaries, including Carlos Fuentes, ribbed “Elenita” for not participating in Mexican literary circles the way she ought.

She kept writing. Finally, in 2014 at age 82, Poniatowska won the Miquel de Cervantes Prize, the highest award for literature in Spanish. Just this year, at age 91, she has won the Belisario Domínguez Medal of Honor, México’s supreme state honor.

And she keeps writing, while famously doing all her own chores in her book-lined house in Mexico City’s Chimalistac neighborhood. Poniatowska arrived in the city at age 10, the child of a Paris-born, aristocratic Mexican mother and a Parisian-Polish father, who chose to emigrate from the war in Europe. Born May 19, 1932, she went to work in 1953 as a society reporter and celebrity interviewer for the newspaper, Excélsior. She was one of the founders of the newspaper La Jornada, the feminist magazine Siglo XXI, and the film institute, Cineteca Nacional.

I discovered Poniatowska through an essay she wrote on the Guatemalan poet, Alaíde Foppa, who disappeared and was presumed assassinated by a death squad in 1980. (An essay on Foppa appears in this issue of Cable Street.) Foppa and Poniatowska shared a Central American-European heritage. Both risked their literary reputations by publishing short books with illustrations—Foppa’s Elogio de mi cuerpo and Poniatowska’s Lilus Kikus. Both voiced a determined feminism and egalitarianism, which manifested in direct action in service to the poor and women in their societies.

Poniatowska has never written about her society from a distance. She spent extensive time with people from all walks of life, earning the moniker, “The Red Princess [La Princesa Roja],” as an aristocrat who joined the left and battled the class structure. In the hours and days after the 1985 earthquake, Poniatowska took to the streets to give aid to the injured and distraught, even as fellow journalist, Carlos Monsiváis, asked “what the devil she was doing instead of writing.” (Delibovi translation.) When she did finally write her crónicas of the earthquake, her prose expresses all the emotions of her close engagement. This is captured in her vignette, spoken by a woman from Mexico City’s San Ángel neighborhood, on the day of the earthquake (Delibovi translation):

I arrived at the Red Cross to help in any way I could. A man, grossly injured, touched me. I drew nearer to him…he would have been about 65 years old. I took his hand. He insisted:

—Move closer to me, because I am going to die in a little bit and I want to die looking at a pretty woman.

It’s not that I’m pretty, but to him, in that moment, I seemed pretty. He never complained. He said nothing more. He no longer had strength. I was struck by his integrity.

He died.

This passage exemplifies an enduring contribution Poniatowska has made to literature. As both a reporter and a crafter of fiction, she has developed two important and interrelated literary genres, testimonial narrative and fictionalized biography. In these genres, Poniatowska skews the frame: a reader expecting facts finds the intensity of fiction; the reader expecting fiction also finds facts. Poniatowska is unrivaled in her ability to write nonfiction testimony that is vivid and dramatic. as the quote above shows. She also writes fiction in which autobiographical details gradually emerge, like stones in an ebbing tide, as in this excerpt from her story, “The Canaries [Canarios]” (Henson translation):

When I was a little girl and would eat pumpkin seeds, my mother would say, “An orange tree is going to grow inside you.” Or an apple tree. The idea thrilled me. Now it’s the canary that causes a tree to grow inside me. I echo. I’m made of wood. His singing has unleashed something. Mine is a sad house, stuck in time, a house full of monotonous rituals, tidy. It lets loose now. “I’m alive,” it says to me. “Look at me, I’m alive.”

And Poniatowska, too, is very much alive as she begins her 92nd year. She needed that long, long life. Survival was the way she proved her greatness to a world that, sadly, still doubts women.

—Dana Delibovi

* * *

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Christopher Sawyer-Lauçanno for inspiration and insight on Elena Poniatowska.

Read more:

Books and stories by Elena Poniatowska mentioned in this essay are available in English translations:

- “The Canaries,” In: The Heart of the Artichoke, trans. George Henson. Salt Lake City, UT: Alligator Press, 2011.

- Lilus Kikus and Other Stories, trans. Leonora Carrington. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2016.

- Massacre in Mexico, trans. Helen R. Lane. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1991.

- Nothing, Nobody: The Voices of the Mexico City Earthquake, trans. Aurora Camacho de Schmidt and Arthur Schmidt. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1995.