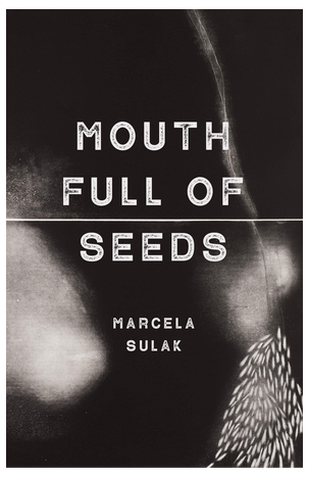

by Marcela Sulak

A Poet and Translator’s Lyric Memoir, reviewed by Elissa Favero

Black Lawrence Press, 2020;

ISBN: 978-1-625578-09-9

Italian fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli gave the poet Marcela Sulak the title for her lyric memoir, Mouth Full of Seeds. Sulak and her daughter attended an exhibition, where they read Schiaparelli’s words, “…with some difficulty [I] obtained seeds from the gardener, and these [I] planted in [my] throat, ears, mouth…” (35) Sulak riffs on this quote. “To have a mouth full of seeds would be a wonderful thing, to be drowned, a throat filled with hard, shiny points, like the mark left by the tip of a pencil, poised on a page.” (35-36)

Words at an exhibition, a day with a daughter—reminding us that a memoir is tethered to the events of a life, although not always in sequence. Sulak’s lyric memoir is not chronological. It moves by image and language to describe a sinuous life. Sulak’s Turkish surname “…means water―that which flows across boundaries.” (108) Sulak’s recurrent motifs and inclusion of other voices make Mouth Full of Seeds a fluid memoir of an itinerant life-so-far.

While Mouth Full of Seeds flows in word pictures and patterns, Sulak imposes a kind of order via the numbered sections of the book’s first and last pieces: “Drawn That Way” and “My poetry I believe is located. It is I who is not.” These prose poems, two of the book’s longest, also provide some of its most concrete facts about Sulak: She is, we learn, a Texas-born immigrant to Israel and also granddaughter of Czech immigrants to America; a former Catholic and adult convert to Judaism; a scholar, translator, single-mother, daughter of rice farmers, and adult gardener. The book’s seven sections coalesce around different themes that flow though Sulak’s life experience.

For example, in the third section, “Ordinary Water,” three pieces braid the gendered expectations of traditional folk and fairy tales with tribulations of contemporary life, such as washing machines and dating sites. In the fourth section, “One Bird or Another,” three pieces bring together the flights of birds and the dramas of human lives. Plants weave their way consistently throughout Sulak’s verdant prose: “…it’s a waste, and shame that we can’t always live as paintings by Giuseppe Arcimboldo, our bodies banquets in which ripe fruit never drops, our mouths the berries, our limbs already roots, our heavens seasonal, our seasons always full. (84) Here and elsewhere in the book the earthly is paired with the celestial. As Sulak submits in the tercet poem “Cell,” “The secular is / the mirror of the / sacred…” (21)

In a collection that’s deft at bridging places and linking motifs, Mouth Full of Seeds also moves among different voices, especially those of women. In the book’s first piece, Sulak addresses her mother’s incredulity at what she calls Sulak’s “freedom of spirit” (3) by speaking back to her in mimicry. “I have no idea, Mama,” she writes in response, “where I got my freedom of spirit!!” (5) A few pages later, Sulak invokes a cartoon character, inserting a pop culture reference in the midst of papal commissions, Jewish ritual, Sulak’s fears of gender-based violence, the hassles of daily life in Tel Aviv, and the work of tending a garden. “‘I’m not bad. I’m just drawn that way,’ says Jessica Rabbit in Who Framed Roger Rabbit. / I am drawn that way, too.” (8) Here, the writer’s diction resonates on multiple levels, and “drawn” means not only “sketched” but also “pulled” or “attracted,” as Sulak has been pulled and attracted to many places and to many registers of reference. The prose poem quoted above—“Elsa Schiaparelli, Miuccia Prada, Amalia, and Me, at the Met”—names the poem’s female speakers; by the last paragraph, the voices of the four women are crisscrossing in an interlacing conversation that spans the contemplative, historical, sartorial, and familial.

“Dear honeysuckled, have all the mosquitos died?,” Sulak asks in the book’s second piece. She seems to write to the plants of her Texas childhood while lamenting her youthful unhappiness there. “Dear me,” she continues, “how awful it all was, and how familiar. Dear home, how I hated you. How I thought something was missing all that time. Dear me, it was me. I was the missing.” The piece concludes with these words: “…dear history of my haunting, I can love almost anything.” (17) Removed from her first home by geography and time, Sulak herself seems no longer to be missing, but she does appear to long for parts of what she’s left behind. Other things she’s taken unwillingly, though they stay with and haunt her. These are the seeds she’s gathered and sowed. In Mouth Full of Seeds, they bloom into a voice rich with potatoes, folk tales about laundry, storks, and women talking while remaining rooted in the events and impressions of a life.