An Interview With Nandana Dev Sen

Nandana Dev Sen is an actor, writer, translator, and child-rights activist. Her unconventional career has taken her from major roles in over 20 international films to the creation of six children’s books. In 2021, Sen published Acrobat, a Bengali to English translation of the poetry of her mother, the renowned poet Nabaneeta Dev Sen. The book is a major contribution to the international availability of Bengali literature—one of the world’s richest literary traditions, yet one of the world’s least translated. (For two poems from Acrobat, in Bengali and English, click here.)

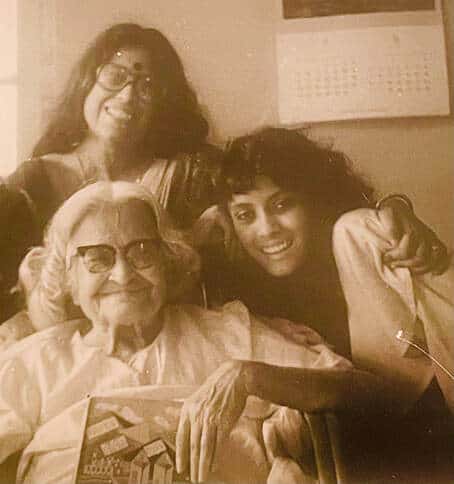

Sen spoke with Cable Street’s Dana Delibovi from a cheerful room in her home, filled with books and family photographs. Although Sen lives in the US, she spends a good part of her time in India, detouring often to travel to many other nations. Our talk began with a discussion of the family legacy that instilled in Sen a love of words. Both her mother and her grandmother, Radharani Devi, were poets, and her father is the Nobel-prize–winning economist Amartya Sen. We then conversed about words themselves, their power, and the translations that open one culture to another.

actor, writer, translator, and child-rights activist, amid her books and family photographs

আরো

DANA DELIBOVI: Tell me about your life as a child. What was it like to grow up is such a literary family? Did you feel any pressure to achieve or to pursue specific academic goals?

NANDANA DEV SEN: I grew up in Kolkata in an all-female household. I lived with my mother, my grandmother, and my older sister Antara, in a beautiful, rambling, chaotic, old house called Bhalobasa, which is now a heritage property. The house was a beloved center for literary and cultural soirees of writers, artists, and musicians. I was close to my dad, but saw him only a few times every year. I moved closer to him only when I shifted to Cambridge, MA, for college.

Both my mother and my grandmother were very successful poets who also had strong political voices. Not having any males in the house meant that my sister and I were never really comparing ourselves to boys. We saw two formidable feminists confront the world. The confidence that I feel has a lot to do with that.

I was also raised in a house full of books. We would get driven out of rooms to make space for books! Our childhood was spent going to poetry readings, literary festivals, and book fairs, rather than the zoo or the circus or theme parks. I complained about that as a child, but it had a lot to do with what I grew up to love — poetry and argumentation. Yes, I did grow up in a celebrity family—but my mother was the superstar then, not my dad, who at that time was celebrated only in academic circles.

I have to give full credit to my parents for never putting me under any pressure. I have changed my life around many times—moving between countries, turning 180 degrees from being a literary editor to making independent political films to writing children’s books, with many smaller turning points in between. My parents took all of this in their stride.

Still, I wanted to move to a place where I would not always be identified as a child of a family that was forever in the public eye. I needed some anonymity as a young person, to discover my own self. My mother was not keen on my leaving Kolkata for the United States as an undergraduate. But Ma also understood that this was something I really wanted to do. So we made a deal: I could only apply to the four US universities that she knew personally. If I got into one of them, I could go. If I didn’t, then I would stay in Kolkata and go to Presidency College, as both my parents had done. Happily, I did get into one of my mother’s chosen four.

DELIBOVI: When you were growing up, what were your dreams? Did you think you would be involved in literature or something completely different?

SEN: Honestly, I didn’t grow up asking myself those questions. I had interests, but I didn’t have practical visions of the future. I was a bookworm and everybody in my family was a writer, so I knew that my life would be in the world of the creative arts. But I didn’t have a professional dream in the way some very focused kids do.

In India, we are encouraged to set a goal when very young–will you study the arts, or science, or commerce? Though I was a good student, I had never conformed; I reacted against that reductive model. I was not one to pIan where I hoped to be in 5 or 10 years. I felt from an early age—although I didn’t have the language then to talk about it—that what’s important is to be true to the moment, and explore all of your creative passions.

DELIBOVI: Tell me about that exploration.

SEN: I was always drawn to cinema as a medium. I thought, and still believe, that film has a truly transformative power. But at Harvard, film studies were not as strongly developed as yet as the literature department, so I ended up choosing literature and creative writing because it was a stronger curriculum.

My first job after graduating was as an editorial assistant and I soon became an editor at Houghton Mifflin Company. During my five years there, I was very lucky to edit books that I really loved, like the Best American Essays or the Riverside Shakespeare.

I was still interested in film, so I got a little camera and started shooting short films. I went on to study film at the University of Southern California, where I continued making shorts but also was offered the lead role in my first film— Gudia (The Doll), directed by Goutam Ghose, and based on a story by one of the greatest Bengali fiction writers, Mahasweta Devi. It took me by surprise, and I needed some time (and some convincing) to accept the offer, but then I discovered that I really loved being an actor. Here was a kind of work where you truly had to be naked with your emotions and could not hide behind your intelligence. We come from a culture of argumentation, where we can tiptoe around matters of the heart very cleverly. But with acting, I couldn’t do that. Gudia officially premiered at Cannes, and I suddenly found myself to be a rather busy actor, with agents in New York, London, and Bombay.

I went on to act in more than 20 international films, all with a social or political consciousness at heart, exploring such topics as freedom of expression, religious war, LGBTQ rights, apartheid, child sexual abuse, or the rights of children with disabilities. Along with way, I started advocating for children’s rights. I started writing professionally—screenplays, essays, children’s books, translations of my mother’s poems. My mother and grandmother had always thought I would be a writer, and when I was in college both wrote to me—what beautiful letter writers they were—about the importance of writing every day. I’m glad that Ma, at least, had the chance to see her prediction come true, although she had always been very supportive of and excited by my acting work.

DELIBOVI: One way or another, the power of language has been a part of everything you’ve done. Could talk a little bit about what you love most about words and languages?

SEN: All my life, I’ve been surrounded by the “über-verbal.” My mother, my father, my grandmother, and everybody who gravitated around them. I took from them, not a love of just words, but of the whole experience of language.

I love the Bengali language, but I had taken my mother tongue for granted, the same way that you take your mother’s love for granted. Even though I had translated my mother’s work throughout my life, working on Acrobat — delving into 60 years of her poetry — brought a nuance to my relationship with my language.

It’s also true that the language of poetry had always occupied a central space in my development because of my family—my matrilineal legacy made me love and rely on poetry, and to this day, I make sense of life through poetry.

Radharani Devi

DELIBOVI: During all the years you translated your mother’s work, was there a point while your mom was still living where you said to yourself—”I have to make Acrobat, I have to make this book?”

SEN: In the past, I had translated my mother’s poetry for a time-bound event or presentation. Then, as a surprise for her 75th birthday, I self-published my translation of her latest book, which in English is called Make up Your Mind. When my mother was diagnosed with cancer, she had great equanimity about her illness, but I knew she felt a certain sadness that her work hadn’t been published internationally, because of the choice she made to write in Bengali—even though she knew and accepted the cost of this choice.

I’d made a list of the things that I wanted to do with my mother before she died, and an internationally published collection of her poetry was very much on it. Then, something brilliant happened. Somehow, a copy of Make Up Your Mind made its way to Jill Schoolman of Archipelago Books., and she wanted to publish a collection of my translations of mother’s poetry. I explained that my mother was unwell, so Jill sent us a contract within days. Together, my mother and I chose the cover image painted by the great Bengali poet, Rabindranath Tagore. Two weeks after we delightedly signed the contract together, my mother was gone. But she had been so happy to know that Acrobat would happen.

DELIBOVI: In working on Acrobat, what have been your biggest challenges in translating from Bengali to English? What were your biggest joys?

SEN: Translation is such a personal journey. That is the challenge and the joy.

There are the issues translating poetry in any language, like dealing with rhyme and meter in the original. Then, you have to decide how to approach the style and priorities of the specific author. My mother was superb in her rhymes and her metrical structures, meticulous about form as well as content.

Ma also loved alliteration and assonance, and she excelled in making up neologisms. In her work, she made beautiful references to epics in Bengali literature and international authors like Shakespeare and Kafka. She included references to political events in India, such as the [Hindu-Muslim] riots of 1992.

In translating my mother’s poems, I chose to make sure that any poem she rhymed in Bengali, I would rhyme in English. If she used a particular metrical structure or rhythm, I would be as true to that as possible, and if that particular rhythm was not possible in English, then I would find an equivalent rhythm that could give the same emotional impact.

It was also important to me not to have any footnotes. I do not like reading footnotes in poetry, as they interrupt the emotional flow. Sometimes it’s inevitable—if I were translating the Mahabharata, I probably would need to footnote it — but for my mother’s work, which is so visceral, I wanted to translate it in such a way that the sense evoked by the original word was captured in the translation. And beyond that, I incorporated enough clues so that you could remember a reference, or else look it up. I tried to spark the reader’s memory, or curiosity, more by association than exposition—for instance, this invokes an epic battle as in the Ramayana, this refers to Kafka’s Metamorphosis.

This is why translation is so very personal. You make personal choices based on what you think is critical to be true to the spirit, and the music, of each poem.

DELIBOVI: You set a high bar for yourself, trying to reflect the originals’ rhymes in your translation—and you used rhyme in subtle and unexpected ways.

SEN: Well, I love rhyme, and more importantly, so did my mother—so I wanted to retain it as it makes her poetry very unique. But if there were ever a moment where, by focusing on the rhyme, I would lose out on something deeper in the poem, then I wouldn’t have sacrificed the content to the form.

Rhyme is one the reasons it took a long time to complete Acrobat. Many times, I would do a version and think “OK. I’ve got the rhyme, but I don’t really have the soul of the poem.” I would just throw it out and start over again. To get to the heart of some of the poems, I realized I had to write in rhyme, but not make a literal translation. I had to think about how my mother would write it as a rhyming poem in English. I had to navigate the translation of each poem a little bit differently, depending on what I felt was most organic to it. I was glad that by the time I completed the manuscript, I did render in rhyme every poem that Ma had written in rhyme.

DELIBOVI: The majority of our readers don’t speak Bengali. What do they need to know about that language? Is there something really special about Bengali?

SEN: It’s a very playful and extremely musical language.

DELIBOVI: That really shines through in your translations.

SEN: Thank you so much! The inherent play within the language is one of the key things that I did not want to lose in translation. There’s a great deal of power in that play.

I love how ambiguous Bengali can be. That’s part of what makes it so playful— it’s naturally evocative, vocal, and poetic. There are words that can mean so many different things. You can make up new words by compounding more than one, with endless possibilities. When reading the compound words, if you know a little bit of Sanskrit, you can see the ancient roots of the words. Sometimes it feels like a certain word has centuries of cultural history embedded in it.

If Bengali is ambiguous, it’s also extremely specific. This might sound like a contradiction, but it’s really not. We have specific names for things English does not. We have a name for your mother’s older sister’s husband, for your younger brother’s middle child. A very special literary tension arises out of this ambiguity and specificity.

Bengali is also a self-consciously beautiful, flexible language. It can be ornate, but also conversational. My mother was a unique writer who managed to integrate the ornate and the conversational effortlessly in the same poem. She dressed her poetry in all the filigree jewelry as well as the oxidized bits!

A particular challenge for any translator from Bengali is that it’s very pithy. You can express a great deal in just a few words. When you translate a line into English, it can easily become a paragraph if you want to include everything that’s expressed. For me, as a translator, Bengali unfolds like one of those travel bags that’s small when closed, but when you unzip it, it becomes huge, capturing a whole life as it is lived.

DELIBOVI: In doing the research for this interview, I learned that Bengali literature is among the least translated literatures in the world. Who are some writers in Bengali that we ought to know, who the translators among us ought to tackle, maybe in collaboration with a native speaker?

SEN: That is absolutely true. Bengali is one of the least translated languages, though it is spoken by one of the largest populations across the world when we include Bangladeshis, as we must. And it’s also one of the richest literatures in the world.

Tagore is our most translated poet, but I think his songs should be better known globally. He’s like Bob Dylan, a poet who also composed the catchiest, most soulful and popular songs. People sing Tagore all the time. Every day, I make sense of things that happen to me through Tagore’s songs. I feel that his poetry has often (but not always) been translated inadequately, either as a kind of mystical prayer or as something far less accessible than it really is.

My grandmother’s work needs to be translated. She was a fascinating writer who chose to write under two names—Radharani Devi and Aparajita Devi—with two distinct feminine voices. Radharani’s poetry was earnest, self-searching, idealistic; she wrote about a woman’s place in society, the upliftment of women, and throwing away the shackles of expectation and domesticity. Aparajita’s poetry was erotic, and quite shocking at the time. It spoke of women’s desires, of extramarital affairs, of the games you play with your husband or lover.

Other poets of my mother’s generation that the world should know are Sunil Gangopadhyay and Shakti Chattopadhyay. Another influential, older poet is Jibanananda Das. Ashapurna Devi was a Bengali fiction writer whose work was transformative but has hardly been translated. More Bengali prose has been translated than poetry, but even so, there’s not enough of Bengali fiction available in translation either. My wish list is, honestly, very long!

DELIBOVI: That’s a powerful literary legacy. How has translating Acrobat helped you remember your own part in that legacy?

SEN: The experience of creating Acrobat was a way of staying connected to my mother. But it was also a way of discovering my mother in a way I hadn’t when she was alive. For example, there is a poem in the book called “This Child,” which my mother wrote just after my older sister was born. The first line is: “One day this child too will die.” She wrote this in 1963, a time when, expressing your anxiety about motherhood would surely get you identified as a bad mother.

Translating that poem, I understood this aspect of her anxiety for the first time. Working on other poems in the book, I uncovered layers of her emotional history that I hadn’t fully grasped before. My mother and my grandmother had a complex relationship, full of conflict and tension but also unrestrained love. I understood this better somehow through the poetry, when they were gone, than when I was living with them in the same house. I understood my parents’ marriage disintegrating and the loneliness of their estrangement. I understood why my mother always said her poems anticipated what was going to happen—how the poetry knew, how it was an oracle for her. I could see how true that was, when looking at the dates of certain poems.

I’m thinking of doing a multigenerational memoir, a book on the literary and feminist legacy of my mother and my grandmother, seen through a daughter’s lens. The tentative title is Mother Tongues. My mother and I had started this project in 2018, before she was diagnosed with cancer. We spent that summer gathering our thoughts and making a plan, but we took a break from it after my mother became ill. When I worked on Acrobat—in that strange, dark time of the pandemic, a time of mourning for the whole world as well as for me—somehow Mother Tongues started breathing again. I’m still thinking about how best to write about our journeys—whether the narrative would be in all three of our voices, and if our stories could unfold in part through poetry. I haven’t answered all my own questions yet, but I do want to go back to it now. I am ready.

আরো