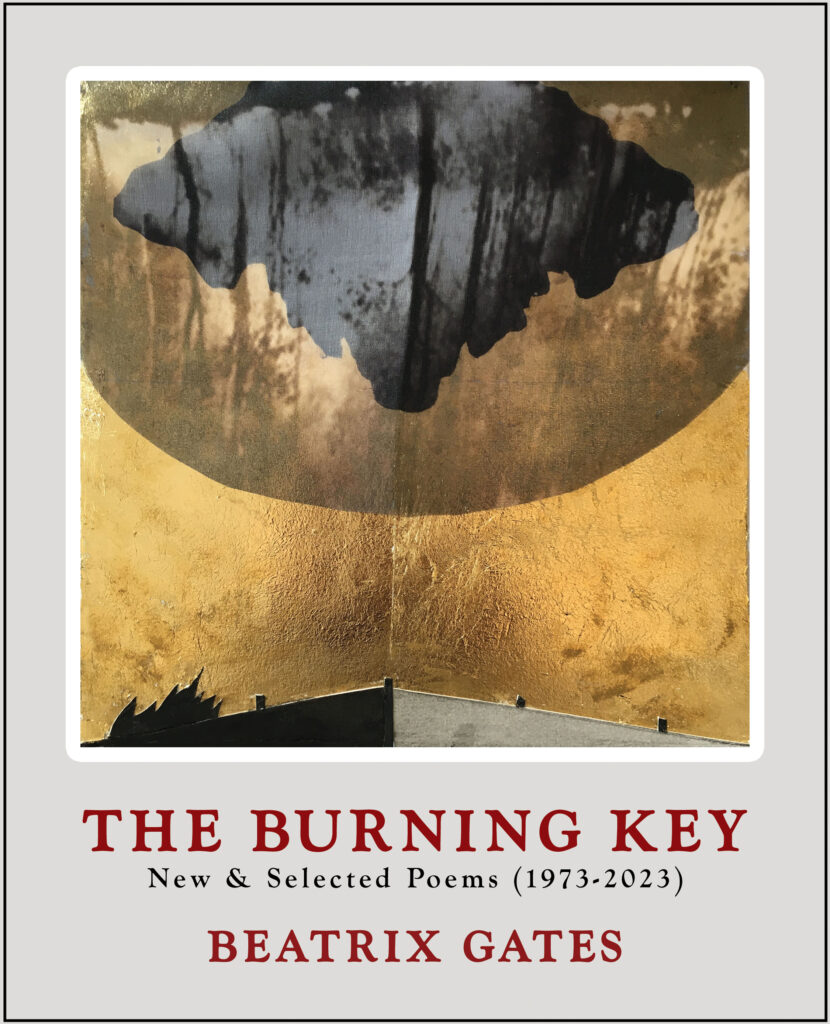

The Burning Key: New and Selected Poems (1973–2023)

by Beatrix Gates

Love haunts. It follows us, a remembered flame that flickers in even in the simplest things. It returns when we hear the wind at night; it rises when we touch that old purse that should—but can’t—be thrown away. This haunting, smoldering love colors every page of Beatrix Gates’s The Burning Key, the poet’s new and selected poems, spanning 50 years of glorious work.

The Burning Key begins with “new and reclaimed poems.” These poems unpack recollections of people Gates has loved in the most complex and surprising ways. When people are friends, a hint of the weird or alien pervades their bond. For instance, the charming, 4-part poem, “Songs for the Faerie Kingdom,” engages a friend named Ron in celebratory verse that evokes both gay pride and the supernatural. And even when friends are lost, we love them as they repose in memory’s garden—as pictured in these rich images from the poem, “Jean here—”:

Is that you the sheer

strong mist murmuring

to the Moon

I feel the poem

change since you

are not outside

You are inside

How human

cries a grief color

I wrote waves

where you might lay a night flower

or a bead on a stone

or rain necklace of mist

for the throat

Most of The Burning Key comprises selections from books that Gates has published. Gates is well known as an activist poet, and her work refers clearly to LGBTQ+, feminist, and anti-war activism. What resonates most, however, are not the historical and cultural references, but the compassion she feels through struggle, time, setback, and success. This resonance echoes deeply in the poem, “Seeking Tenderness,” originally from Gates’s 2006 collection, Ten Minutes.

“Seeking Tenderness” is dedicated to Matthew Shepard, a gay student from Wyoming whose murder sparked the movement to recognize hate crimes as distinct offenses; the poem portrays Shepard’s killing, and also references another murder that drove hate crimes legislation, the dragging death of James Byrd Jr. in Texas. What could have been, in other poets’ hands, a screed, is instead a poem of profound, universal love:

Later, he will fly,

wrists still bound to the fence,

the wind in back of him

easily lifting him off his feet…

He will be like billowing

clouds that rake the plains

this time of year, change hour to hour, comb the grasses

silver, then red, keep coming.

How does Gates imbue her poems with love in all its manifestations? This is a question of craft that burns within poets working now, in an age when cold cynicism is the default mood. Many writers would like to move their work from frosty to warm, but don’t know how. But Gates knows, and she accomplishes this emotional feat with two elegant techniques,

First, she never shies away from the human body, but embraces it fully in her images. Hers is a poetry in which the body of a beloved person is central to both the natural and human-built world. A brother’s gash on beach rock, a father’s gray eyes, lovers’ limbs splayed across a bed in the moonlight—the body is always held close in Gates’s work.

Second, Gates has perfected an enjambment technique that warms the tone of her poems. She often places her break just after a simple one- or two-syllable word that is assonant with other line-ending words. The effect is a sense of intimacy, an empathic timbre, an ambiance of kindness, as exemplified in the poem “Cut Scenes.”

Call your brother home

Slowly say the bones.

I wake in the night— blossom,

no leaf. I am falling, yes, this is

the random float of beauty, full

veins of color detached from the tree,

the air capable of all things.

I wake in the fullness

of my still untethered past, body

whirling on my bones praying to be let down

on the ground where I can walk away.

These observations do not in any way imply that Gates’ work is limited only to the traditional “feminine” virtues of nurturing, loving-kindness, and care for others. Indeed, the poet defies gender roles and tackles a broad range of robust subject matter in her work. This is perhaps most clearly shown in Gates’s translation of poems by the Spanish writer, Jesús Aguado.

Aguado’s intriguing poems contain “a voice within a voice.” He writes as the fictional Vikram Babu, a seventeenth-century Indian mystic and basket-weaver who writes without modern guile or hesitation. Gates, in conjunction with Electa Arenal, renders Aguado’s brutally frank poems with a candid, spare English diction. In one translation, for instance, “Como el que mata a un niño y lo desuella/y machaca sus huesos/y quema sus tendones/y da a comer sus vísceras a un perro…” becomes the equally blunt, “Like the one who kills then skins a child,/grinds its bones,/burns its tendons,/feeds the guts to the dog…” Aguado’s poems can be fierce, but they are works of the heart, just as Gates’s poems are. The poem quoted here, that begins in extreme violence, ends by asking us to turn inward, to see if such violence lives within us. The implication is that we must replace savagery with love.

The Burning Key is an excellent book, which might have been even better if the selection of poems had been pared down a bit. In particular, the number of very long poems might have been reduced, and limited only to the very best examples of that type. Gates has written many longer poems with a narrative structure, but she really soars when she embraces the disciplines of lyric poetry. A more vigorous edit of the longer poems would free the reader to savor the lyrics.

Three poems from The Burning Key have been reprinted in this issue of Cable Street. Love permeates these three poems. Every line is infused with the energy of people, living or departed, that Gates cares about—the “the beloveds” of the book’s dedication page. The final words of one of the poems, “Last night” epitomize this depth of feeling:

Later morning, I tell the young man, my old friend’s grandson on the phone translating

for her in her deafness: I love your grandmother very much, and that means

I love you too. He understands, Yes, he says, I send it back to you.

Yes. Loving means loved.

— Dana Delibovi