The Vanished Publisher IV

Tobias Meinecke & Eric Darton

To read the three previous installments, see issues 4, 5 & 6, or follow the links at the bottom of this page.

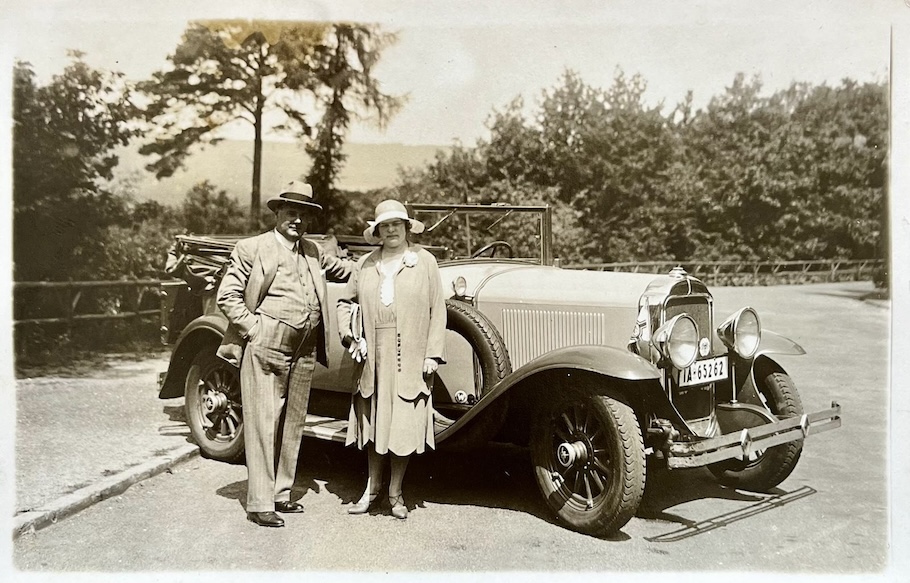

Alma Klemm-Dietrich and second husband Willy Dietrich with their 1929 Buick.

Berlin, 2025

Those two great-grandsons you hear Hermann nattering about, Boris and Tobias? Hermann never met them. I did. When they were wee little things. And I remember them growing up, becoming teenagers. Who could’ve imagined that these two would one day pull our lives back onto the stage? Certainly not I.

Hermann died too young to have known any of our grandchildren, let alone the next generation. He left us at forty-four, or nearly – No, it was exactly forty-three and ten months – as Hilde, insufferable Hilde, would invariably interject whenever I mentioned his passing public.

Hilde and I never got along as well as I would have liked. It was always Hilde, but never Illa, who picked fights with me over anything, no matter how trivial. How could twins turn out so differently? I couldn’t tell you, but maybe someone should study that! Throughout their childhood they were like two peas in a pod, inseparable – they even loved to dress alike, not because Mutti made them, but out of their own free will. On top of which, they married a pair of best friends, Ludwig and Alex. But as they grew into adulthood – watch out – fire and ice. Hilde, full of self-righteousness, quick-tempered, melancholic and vengeful. Illa, on the other hand, always the free spirit: rebellious, brimming with enthusiams. And a party animal into the bargain! Of course, you’d never guess this from family gatherings where everyone was laughing together – loudly, but on their best behavior.

At bottom, I think my constant clashes with Hilde were about Willy, my second husband. Illa and Alex never made a peep when, on a bit of a whim, I decided to marry again. But Hilde and Ludwig? They made sure to put their three cents in whether I wanted to hear it or not: Willy was a spendthrift, they said, his only talent lay in draining my bank account, which, admittedly, was true. They also insisted he was beneath me socially, though he wasn’t. But right or wrong, they made sure I knew how they felt.

To be fair, I am certain that, between the two daughters, Hilde missed her father more deeply. She took Hermann‘s death as an unfathomable loss. So to see me with a new husband – happy and carefree again – I had no right to that!

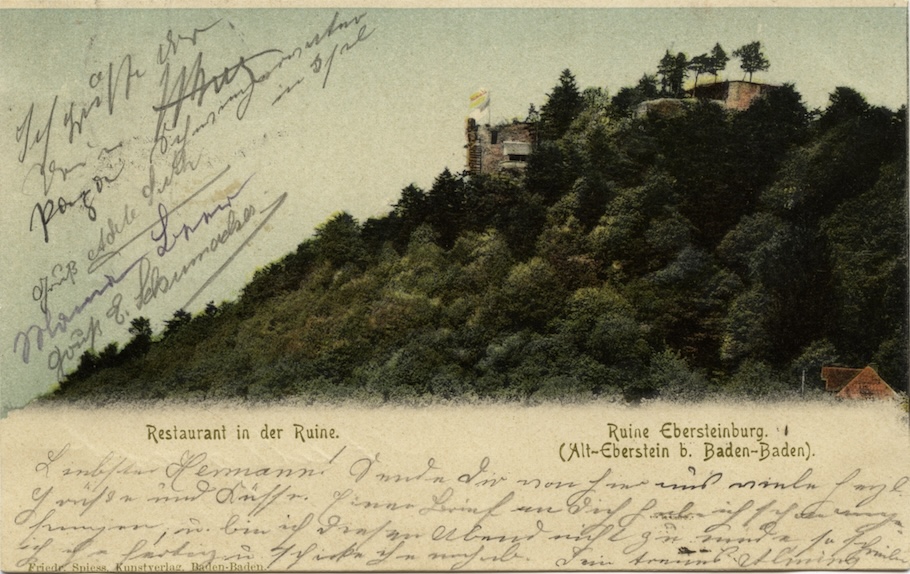

Now Willy, whatever else one may say, was a sweet, docile man. Who seemed to have been born with a ravenous appetite for things he could not afford. In that, he was almost the exact opposite of Hermann. Regrettably, I didn‘t bring him any better luck in the longevity department. In point of fact, the only person I really brought good fortune to, reluctant as I am to admit it, was me. Early on in our courtship, Hermann took me hiking up up the Altes Schloss overlooking Baden-Baden. At the top, he asked, almost off-handely, if I would marry him. When I started to reply, he put his hand to my lips. “But Alma, we must wait until I can provide for you.” No dowry-seeking bounder here. Well in that moment I knew I was the luckiest girl alive.

On August 10th, 1902 Alma used a postcard of the ruins of Alt-Eberstein, near Baden-Baden to write from her hometown, Rastatt, to her fiancèe in Stuttgart. It was there that Hermann has moved to co-found the Kunstverlag von Klemm und Beckmann. She may have chosen the subject because it held sentimental value, since it was there that Hermann had proposed to her almost two years earlier. Her parents also signed the postcard, referring to themselves as Hermann’s future in-laws.

Now although I’d been raised to be a lady and not to scream Yes, yes, yes! across the Rhine Valley towards Alsace and France, that’s how I felt. But as Hermann held me in his strong arms – gallantly preventing me from tumbling down the castle walls – I answered with a decidely unromantic I don’t see why not. Just the same, he seemed delighted.

So yes, Alma soon-to-be Klemm, coming of age in the fin-de-siècle and finding a man of Hermann’s qualities – this was the rarest of good fortunes. He was tall, with piercing blue eyes; full of energy, ideas and projects, a man ready to jump into the lightning fast world of machines and industry, of modern culture and commerce.

So naturally, Hermann’s life was spent on the move. Flitting from here to there: to book fairs, printing houses in Stuttgart, bookbinders in Leipzig, graphic artists in Munich, eminent authors in Berlin, in and out of a thousand bookstores. Meetings with financiers from everywhere. And I was drawn along with him, on a giddy tide – at least unil the twins arrived.

Ah, Hermann: what was the quality that endeared you to me most? Well, here you were, an orphan, unbound by any obligation to family of your own, yet ready and willing to embrace my parents with all the devotion of a natural son.

Needless to say, he was eager to put plenty of distance between himself and his humble childhood in Pomerania. That was something I could readily understand. And he longed to prove himself to my father by achieving even greater success. For Hermann, the privileged life that Papa Beer had provided for his children served only as a benchmark to surpass. By the time we moved to Berlin and into the house on Caspar-Theys-Straße in Grunewald, he had, by any measure, exceeded all expectations.

This three-story corner building at Caspar-Thyß-Strasse 13 Berlin-Grunewald (Schmargendorff), was home to the Verlagsanstalt from 1910 to the early 1940s, when, having been taken over by Hermann’s competitors and former friends in Leipzig, it ceased to exist in any meaningful way. Klemm & Beckmann had moved to Berlin from Stuttgart in 1906. By 1908 the two men parted ways, with Beckmann continuing to publish profitable, if uninspired, travel guides, while Klemm began to build the publishing house as we know it. The front entrance to the left led to the family quarters, while the side entrance led to the company offices.

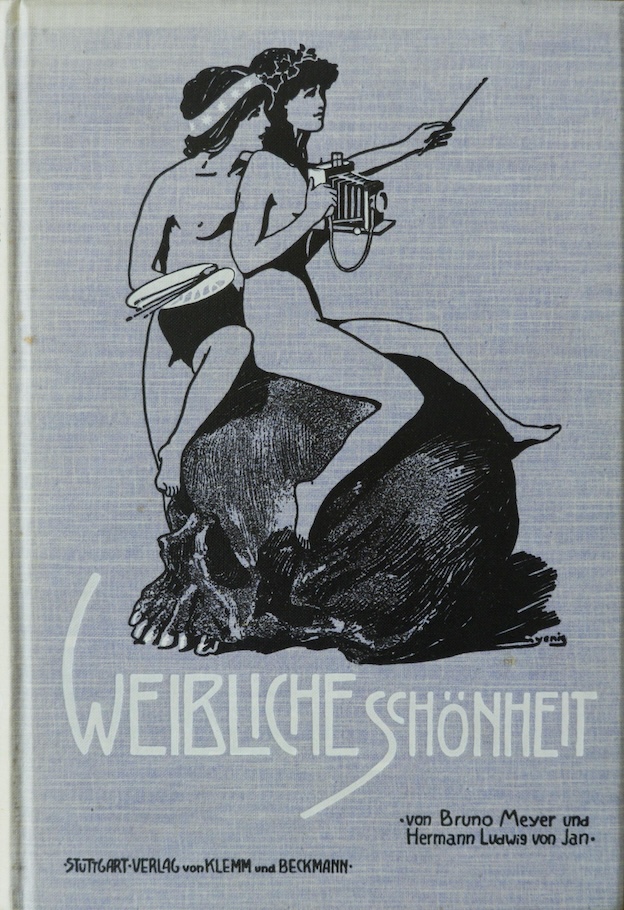

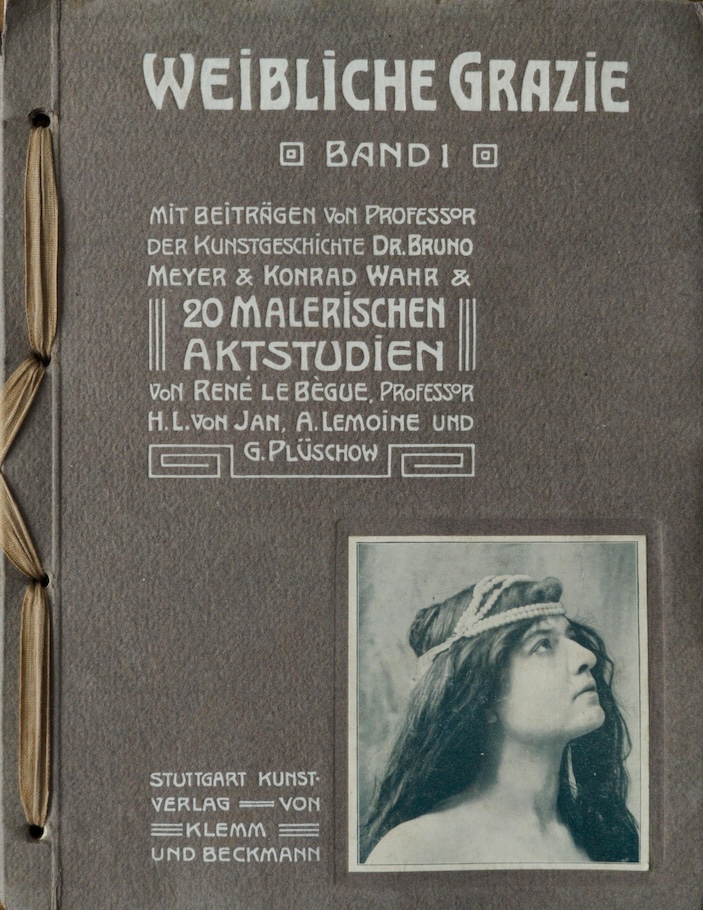

How would Hermann and I have fared had he not departed so soon, if we had grown old together? Would I have been able to keep up with him? Or would he have slowed down for me? In time, might he have come to find enjoyment in those entirely un-businesslike things I so much need to feel alive and contented: traveling, shopping, nights out dancing, people-watching at cafés. Yes, and luxuriating in spas! Perhaps he would have, but I can’t be sure. Willy was naturally more in tune with my inclinations. But then the man had other faults. As I am certain all men must have – though Hermann gave me no true cause to complain. Still, I have asked myself, more than once: on all those travels, did he stray? Oh there were plenty of rumors in the early years, when he was putting together those nude portfolios. The project, he said, had been entirely conceived to benefit our financial future. And indeed they did. Nonetheless, I couldn’t help but wrinkle my nose whenever I heard that the Verlagsanstalt was about put out yet another folio of naked ladies.

As for Hermann’s nose, there was no doubt it was deep in those books‘ preparation. Apart from a photographer, he ran the whole show – even Hoursch was kept at a safe distance from Munich. And then there was the wooden catalog box I chanced upon in the office after the move to Berlin, like something out of the archives of a museum: filled with the photos, names and addresses of scores of young women clearly willing to pose in the all-in-all. One could not help but wonder for what other exploits they might have made themselves available? In the end, I decided it was best, in the absence of really concrete evidence, to tamp down my suspicions and ignore the rumors. What had I to gain from giving way to jealousy? Especially when, and, putting this as delicately as I can, with Hermann I had nothing to complain about in the intimacy department. Even after the twins arrived, we restreated every Sunday afternoon to the boudoir. In that respect we were like a pair of newlyweds until, almost, the end.

Between 1902 and 1904 Klemm & Beckmann published a series of books focusing on nudes. Of high artistic and photographic quality, these beautifully-bound volumes also contained essays from well-known art historians and social scientists. Soliciting contributions from scholars and intellectuals was a strategy Klemm used here and elsewhere to legitimize morally or politically risky subject matter. In the early 20th century, as laws dealing with sexual content became more restrictive, the text sections of these books grew longer, and eventually Klemm & Beckmann stopped issuing new editions entirely.

That said, should anyone require proof of the genuineness of our romance, they need not strain their eyes peering through the keyhole. The evidence is in plain view: our exchange of postcards – in all their multitudes and variety. Even as a child I found postcards fascinating. I remember the first time I held one in my hand. I can’t have been much older than five. I think an aunt sent it to me from Düsseldorf, and it reached us in Saint Petersburg. We had come to Russia to stay with Father for the summer – who was engaged in an extensive railways project. Of course I was too young to read what was written on the postcard. It was the image that captivated me. The card was vibrant in color, it seemed as if some magician had painted it minutes before. I remember a gorgeous lady in purple, gold, white, dark greens, and a bright red ribbon, wearing the most spectacular hat laden with flowers – smiling out at me. She stood in a marbled hotel lobby, while a dove landed on her outstretched gloved hand. Looking at it, I found I could hardly breathe. I didn’t want to let go of the card. As family lore has it, I refused to let go of the card and took it to bed with me. The next morning, after breakfast, I announced that I was no longer interested in dolls. And I requested that from now on, for my birthday, I only wanted to receive postcards. When I turned sixteen, Mama gave me a set printed with my own portrait – to be sent, presumably, to potential suitors.

It was the same for Hermann. Postcards were his first love. And they provided him with his initial success in a trade. Years before he became captivated by the power of books, when he was still an apprentice at Hanemannsche in Rastatt, he’d crisscross the Black Forest selling the wares of his employers. Yes, his first idea for getting rich was to print and sell postcards. And to that end, he investigated production methods, always keeping scrupluous track of what sold well and what did not, and refining his ideas of how to make his merchandise desirable to his customers.

So it is no accident that it was a postcard with which he communicated to me, albeit in a gentlemanly fashion, his amorous interests. I was home for the summer from my Lyceum in Belgium and one warm afternoon found myself browsing among the tables at the Hanemannsche Buchhandlung with no particular idea what might strike my fancy. Would I finally give in to my girlfriends’ urging and read Die Leiden des jungen Werthers? Was it my imagination that every time I looked up I found the tall young man behind the counter staring at me, then quickly looking away? This wasn‘t the first time I had seen him in the store, but had never before considered him more than a piece of living furniture. Did he think I was trying to shoplift a book? Or a postcard, for I had spent a good deal of time inspecting the rack and had finally chosen one. Now, half annoyed by his attentions, I moved closer to the counter, still pretending to scan the book covers, then looked up, directly into his water-blue eyes. Hermann, didn’t look away this time, but instead smiled and made a very minuscule bow of his head, before turning to serve a customer who had brought a volume to the counter. I heard a tap on the storefront window – there was Mamachen – beconing me to join her outside. Which I quickly did, leaving the postcard atop on a stack of Goethe’s siren song to impressionable young women like me.

”Mein Fräulein. I believe you forgot this at the bookstore!” How to describe the feelings rushing up and down between throat and stomach, as he stood in the entryway of our home holding out the very postcard I had abandoned a half hour earlier? I wager that this is a feeling most women do not have more than a handful of times in their lives. Tremendously flustered, I took the card with a nod of thanks, and used the opportunity to inspect him from head to toe. Neither my curt demeanor nor forward gaze seemed to faze him in the least. He tipped his hat. ”I must return to the store. The owner is away. May I call on you again, Fräulein Beer?”

The audacity. The boldness. How to respond? In the instant I decided to meet him head on.

“And you are?”

“Herr Klemm. But you may call me Hermann.”

“You may visit again upon one condition, Herr Klemm.”

He said nothing, but his eyes asked, And what is that? “That you assist me in building my postcard collection. My albums are still half empty.”

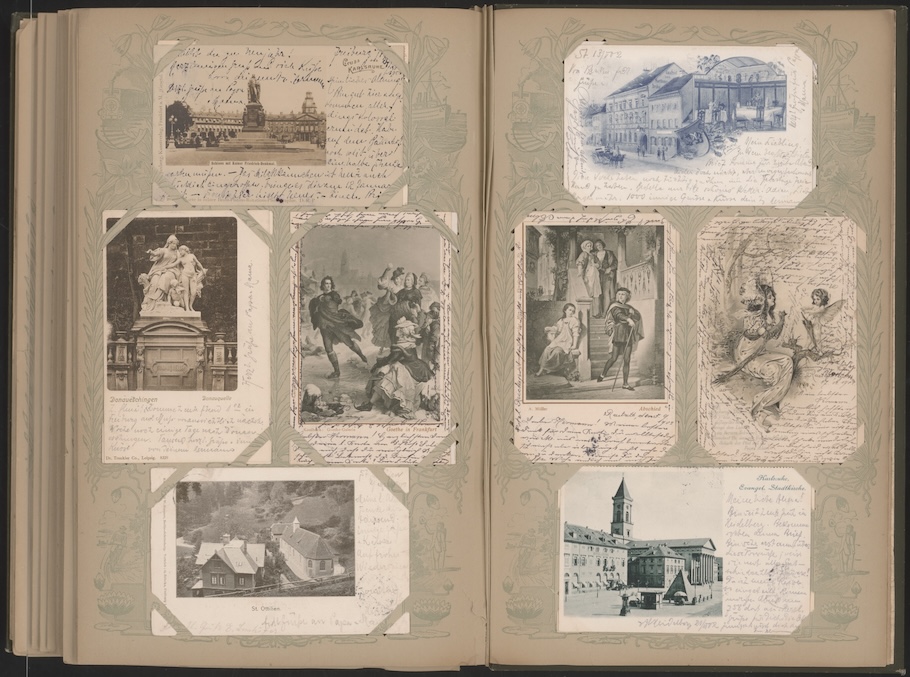

A spread from Alma’s album. More than 450 postcards from their courtship years have been preserved. In one series, sent by Alma to Hermann between September and December 1902, the bride-to-be complains that her fiancé is not answering her postcards in a timely fashion. Though clearly still in love, her tone is angry, lonely and hurt, barely tolerating Hermann’s absence and immersion in a book showing “naked ladies,” however artistically presented.

And so he did. For the next several years, and continuing for years into our marriage, he would send me daily postcards – sometimes twice a day – and I would write them to him as well. When he traveled, which was always, I would rush to the railway station, the train already arriving, and seek out the mail car for I knew it would be carrying his card. It is hard to explain, but I felt so alive in those moments, I feared I might explode.

Hermann‘s cards might come from anywhere, from far flung places or nearby, but they were as reliable as the sun. He would compose them sitting on rough-hewn benches in hidden corners of the Black Forest, in ramshackle roadside inns on the banks of the Mosel, in the lobbies of Grand Hotels in Vienna or Berlin. Or penned in train stations in tranquil towns like Weimar or Neckarsulm. Whether he sent them in the midst of an urgent trip to the printing presses in Leipzig, or from his annual pilgrimage back to his family in Rügen, or while hiking up the Große Belchen, his words were never composed in haste, nor did they ever contain a single doubting phrase. Filled with hope they were, a grand vision of our future together, a future I can assure you, that unfolded almost entirely as he had planned. Often he would send a detailed account of his days, or a gush of ideas, something I loved and needed.

I have always maintained that, apart from the postcards themselves, my romance with Hermann would never have flourished without the invention of the D-Zug, the express train. Nor would the Verlagsanstalt, for that matter. Not only would this wonder of engineering allow Hermann to travel in two hours from his Bohemian attic in Freiburg to meet me in Rastatt, but a postcard he took to the train in the morning would reach me by midday, or if he posted on the afternoon express, by evening. A constant supply of postcards alternating tender sentiments with everyday news. What more could a smitten young woman wish for?

A postal wagon of the German Reichsbahn. The rail system transported all mail within its system, and it was possible to drop off and receive mail directly at the poastal windows. During their courtship Alma and Hermann sent postcards and letters to each other between the towns Rastatt and Freiburg, sometimes as frequently as twice a day.

*

Mid-Atlantic – aboard the SS Bremen, 1931

At this blessedly safe distance, my recollection of the scene feels more melodramatic than real. There they were, fellow inhabitants of the same dimly lit room: five military officers seated in a semi-circle passing a sheet of paper from one to the other – their looks a mix of disgust and repulsion, as if they feared it might give them the pox. I am certain, too, that some of their discomfort had to do with my presence – the idea of any woman attending such a gathering would have been abhorrent in the extreme – yet in this case, they were obliged to put up with it.

Now, for my part, though I am not easily disconcerted, I could focus on little else besides the waves of visceral repulsion welling up within me, for what a sinister cabal they made! A malevolant essence both united the group and oozed from within it, more palpable than any I had ever before encountered. As though their cold, reptilian visages were not enough, upon each uniformed breast – beneath which I was certain, no human heart could possibly be beating – jutted a row of medals, like so many tombstones.

By contrast, Trebitsch, clothed in an English tweed jacket, and with Bohemian wire–rimmed spectacles squeezing the bridge of his already pinched nose – and despite his perpetual wheezing – seemed an almost normal, even pleasant person. My mind flying to absurdity, I imagined him sitting before a cozy fireplace with two Great Danes lying at his feet.

One of the officers, younger and better looking, rose to his feet, put his hands on the back of his chair and leaned forward. “Tell us how you came upon this extraordinary document, Herr Trebitsch.”

“Trebitsch-Lincoln, Herr Oberst. A double name.”

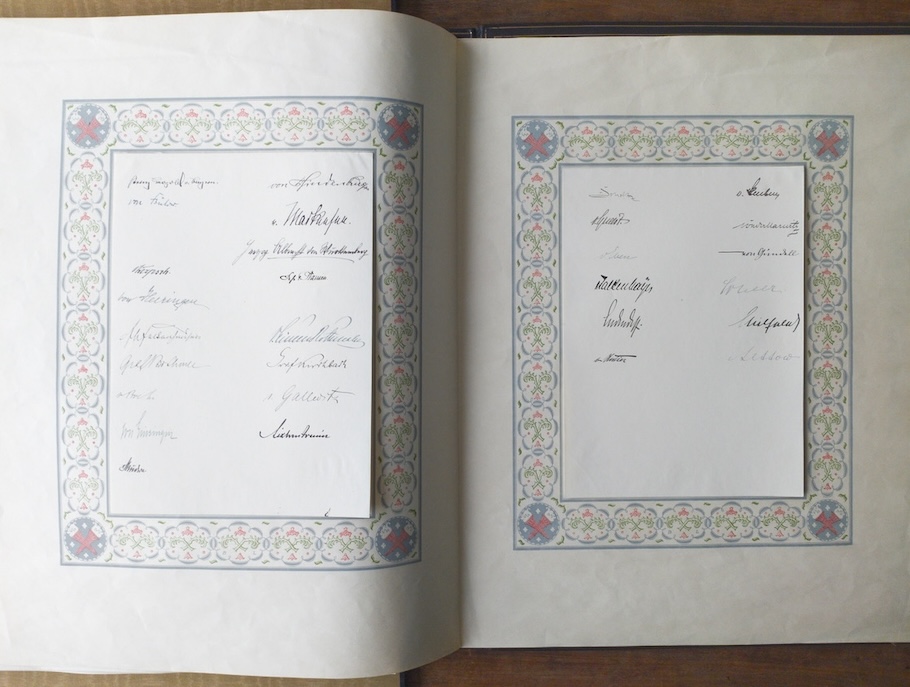

The officer snorted with contempt. Of a lower rank than the others, he had been designated by his superiors to interrogate us plebians. He placed the paper in question on the table before Trebitsch. On it, in two columns like a Gutenberg Bible – were inscribed the signatures of twenty-four German generals. All had been members of the senior staff the day the Armistice was signed.

“How did you come upon this document, Herr Trebitsch-Lincoln?”

He uttered a wheeze which could have covered a laugh. “I am not at liberty to offer names. But I assure you, my source is absolutely trustworty. I have no doubt, therefore, that the signatures are authentic. Moreover, gentlemen, you should know an additional fact: this document is hardly an only child – indeed it has three hundred identical brothers. All of them stacked up neatly in the offices of Herr Klemm’s Verlagsanstalt.“

“And for what purpose were these gathered?“ The question came out at a higher pitch than the Oberst had intended, and he attempted to cover his embarrassment by hooking his thumbs into his belt and expanding his chest.

“They will serve as frontispieces to the luxury, limited edition volume Herr Klemm is preparing for print, even as we speak. The books will be of a size and weight nearly equivalent to the deck hatch of a battle cruiser. Herr Klemm, having commissioned the highest quality artwork and scholarly commentary, intends to sell each copy for five thousand gold marks.”

A rumble of outrage rose from among the officers – it carried the menace of a not-so-distant artillery barrage.

“Some have suggested that the Kaiser himself has endorsed the scheme,” Trebitsch continued blandly. “Indeed His Excellency‘s pet anthropologist is the author of the texts.”

“Since when do generals give autographs to sell books?!“ one of the seated officers exploded. “Such vulgarity is inconceivable!”

“Unforgivable!”

“Treasonous!“

For a moment, the room was quiet, then a scarecrow of an officer who was clearly their leader, began to speak. His voice was soft, slow and deliberate, yet it seemed to me as though the lens of his monocle trembled in barely-concealed rage.

“The men on that list – half of of them were responsible for the Fatherland’s disgrace.” From the other four came murmers of assent. “Those who betrayed us will be made to answer for their sins, one way or another.”

“Money moves minds,” Trebitsch answered, almost gaily. “And even hearts. How many who thought themselves secure have been wiped out by inflation? Whatever the sins of these generals, they are not responsible for the economy – they are among its victims.”

As though he had not heard Trebitsch, the scarecrow continued. “How many of those men were truly willing to die for the Kaiser, one wonders?“

Suddenly, I found myself enraged by this cadaverous monster, so much that I nearly jumped to my feet. What would I have done? Leapt over the table and strangle him screaming I know your kind! Aristocrat! You spent the war safe behind the lines ordering others to run straight toward the enemy machine guns. Mein Kaiser! Mein Vaterland! Those were not the words on your dying lips. Some leader of men you are! The lowest ring of hell is reserved for a hypocrite like you –

By the time I regained my composure, the room was empty. Gone were the officers, imaginary fireplaces and Great Danes. Only Trebitsch remained. He drummed his fingers on the table, and, looking past me, smiled. “Well now,“ he said. “Now we are in business.“

* * *

Well, I had known from the start that working for Trebitsch would be at best a very risky proposition. Yet it seemed the only way. When he had first approached me I was nearly at my wits’ end trying to figure out how to scrape together enough funds to escape from Europe. It wasn’t as if I really had a choice; there was no doubt where the continent was headed. And though he’d paid up, I still needed more. So when he contacted me soon after the officers’ meeting, I again threw caution to the wind. Along with his note, the envelope contained a first-class ticket for the overnight train from Franz-Josef Bahnhof that same evening.

I awoke with a start. Yes, I was alone in my sleeper compartment. But where were the soothing, monotonous sounds of wheels upon rails which had lulled me to sleep? And why was the train not moving? I raised the shade and panic overtook me. A bright moon made it clear that we had halted at a tiny, snowed-in station off the main line. I threw on my dressing gown, and ran down the corridor to my left. No engine, nor other cars at that end. In the other direction, the dining car. I rushed back into my comparment, locked the door and began to dress. Came a knock, then Trebitsch’s nearly solicitious voice. “You are awake, Fraulein? Good. Please come to the restaurant as soon as possible.”

Before me lay a cup of coffee and plates of melange, butterhörnchen and konfitüre. Across the table sat the scarecrow officer. We were otherwise entirely alone. Trebitsch had vanished, along with the waiter. The scarecrow adjusted his monocle. I desperately wanted a sip of coffee, but my stomach turned at the thought of food. I forced myself to meet his eyes.

“I will tell you now the proposal you are going to take to this publisher.” This last word he uttered with a kind of bottomless disgust, as though he were speaking of a species of vermin. I knew the tone, having heard it before, not just from demagogues, but also from relatives – albeit by marriage – in Vienna when they referred to Socialists or Democrats. “It is imperative that you make sure he agrees to it.”

“I think you may be misestimating Herr Klemm. He is not the sort of man who –”

”You are misestimating me, Fraulein, and the will of those I represent. In point of fact, we are not making a proposal that can be negotiated or refused. For your part, you have no choice but to succeed in convincing him to acccept it. How you do so is not my concern.”

Involuntarily, my legs began to tremble, and if I had not been sitting, I may well have collapsed. Still, I could not help berating myself: See where your Mata Hari fantasies have led you? You’re in the shark tank now, my dear – and way over your head. To keep myself from breaking down, I conjured up images of New York, with its amazing skyline. If I got out of this alive, I’d spend a week there, then head for California, this time on a proper train with no surprise detours. Somehow I raised the coffee cup to my lips without spilling it and took a sip, then set it firmly back in the saucer. Words emerged into the room and I realized they were mine.

“As in any battle, the troops can prevail only if they know the objective. And, of course, if the plan itself is sound. Of that, you have said nothing.”

The scarecrow’s face went from gray to white, and for a moment I thought he was going to strike me. But to my surprise, he removed his monocle, breathed on it, and wiped it with a handkerchief. Returning the lens to his eye, he continued in an even, matter-of-fact tone.

“The terms are these: the Verlagsanstalt will receive a cash infusion sufficient to cover the production costs of the big book with which your publisher is so clearly obsessed. But this will only take place under the following conditions. The text must be amended so as to express fervant hopes for the return of the Kaiser to supreme power. Furthermore, the English will be excoriated for their betrayal of the Fatherland and blamed for its subsequent misfortunes.”

“Surely that cannot be all…”

“Nor is it. The fate of your publisher’s big book is entirely contingent on his publishing another volume – a book far more important than his bombastic exercise in pseudo-patriotism.”

“And this book is…?”

“A new novella of Wilhelm Raabe. It is a work of genius, some hundred and twenty pages in length, and celebrating in the most eloquent language the German Nation and Germaic virtues. It will be printed verbatim, and in many thousands of copies. These will be sold for the price of a loaf of bread – two loaves at most if inflation continues at its present pace. Your publisher will use all the means at his disposal to make certain that every bookseller in the Reich is amply supplied, and that Herr Raabe’s masterpiece is zealously promoted above any and all other literary offerings.”

Perhaps because of the absurdity of the scheme, nor less the obvious madness of the scarecrow himself, I nearly laughed. “Mein Herr, it is one thing to manipulate a publisher and another to get a man who has been dead nearly twenty years to write a book – ”

The scarecrow waved his hand dismissively. “That is precisely why we picked him. Few writers have such a wide and devoted following. Fewer still wield so great and enduring an influence upon so many minds. What Raabe says will be believed.” I felt as though the walls and floor were dissolving around me. Did this scarecrow have any grasp of reality at all? Or was it I who had become deranged?

“Raabe has a living daughter, mein Herr. Do you think Margaret Raabe does not know which books her father has written – and which he has not?”

“Fraulein Raabe is of no importance. When you reach Berlin, you will be given the manuscript to deliver to Herr Klemm. You will serve as our intermediary and report to Herr Trebitsch-Lincoln, who will certainly inform us of any missteps on your part. Needless to say, your publisher can have no idea who his benefactors are. He is free to believe what he likes as long as he acts in accordance with our orders. It must be made clear to him that he is not in a position to negotiate or make counter-proposals. Time is of the essence – the book will come out at the Leipzig book fair next spring.”

The scarecrow closed his eyes and leaned back in his chair, an almost rapturous look upon his face. Was he envisioning a future in which the glorious German people, inspired by this poisoned fairy tale, marched forth like the children of Hamelin, their minds free of any resistance to the mad piper’s call?

The special oversized folio edition of Die Feinde Deutschlands Im Weltkriege. It sold for 5000 Reichsmarks and featured original signatures for all Battalion Commanders of the German Army during the First World War. Whatever one might think of the politics of such an endeavor, it was a major scoop for a small publisher such as the Verlagsanstalt.

To be continued…

* * *

* * *