Introduction to Troublemaker, part II

David Sullivan

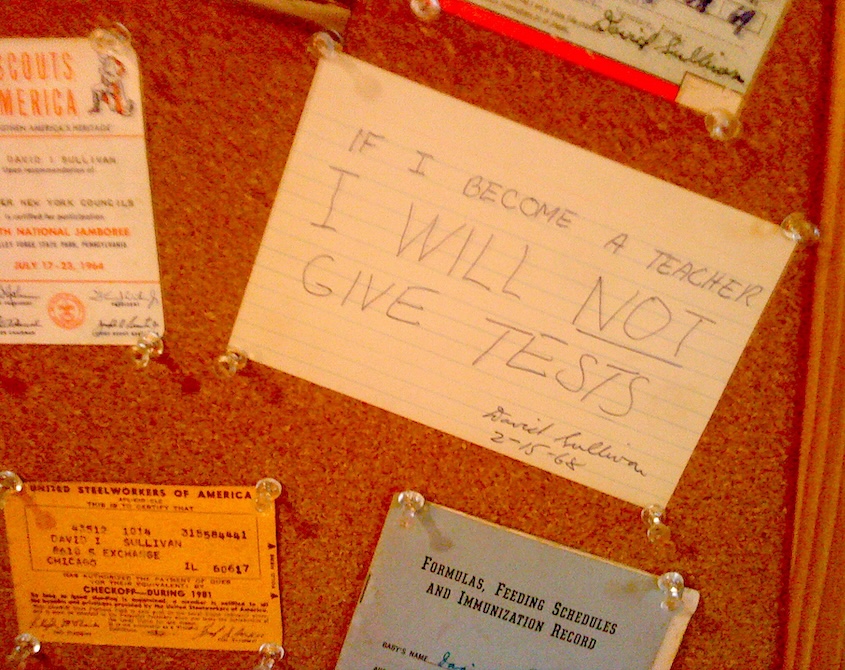

Memorial board for David Sullivan, Chicago, 2009.

Editor’s Note:

This is the second and final part of the Introduction to Troublemaker David Sullivan’s memoir of growing up radical in Greenwich Village in the sixties. Part one appeared in our previous issue.

Beneath the text of David’s introduction, I have included four emails David sent me as he explored and wrestled with his writing process. I present them here in the hope that they resonate with any and all in the Cable Street community of writers and activists who are trying to weave our lived experience, historical perspectives and political thought into a coherent form for the generations to come.

— Eric Darton

Part II

In one important respect Seward Park High School and my experience there as a student was not typical: it was one of the few truly integrated high schools in New York City. [Italics in original.]

My recollections of high school form a curious dichotomy. When I first considered writing about my experience in the high school student movement it was because I wanted to defend what my contemporaries and I regarded as an important part of an authentic social rebellion, one that has been the subject of much criticism after the fact and not a few of whose prominent leaders have recanted their heretical beliefs. It remains a centerpiece of the conservative political agenda in the U.S. to trace the source of our society’s ills to “the liberalism of the 1960s.” While it is easy to dismiss the right wing ideologues themselves, the ideas that they advance have some currency in our society. I thought that I could write an informative and inspiring narrative about how some of my classmates and I came into our own in politics at a young age, organized ourselves, and eventually launched a series of assaults on our school administration in the interest of a just cause for which we cared deeply. I felt this way because, on one level, I remember my high school days with relish. The years 1967, 1968 and 1969 were a three year long adrenaline rush for me, as they were for many of my friends. It was a great time to be alive. In the middle of a mass upsurge such as the country had not witnessed since the 1930s, I had the feeling, not so common in one’s life as it turns out, that I was in exactly the right place, at exactly the right time, and had the will to do what needed to be done. My activist classmates and I thought that we were part of a movement that was shaking the earth. In a complex period, we usually navigated well in the sea of ‘60s politics. I still savor our moments of victory in several political battles. My experience in the high school student movement made me tougher and I am proud that I held up reasonably well under pressure while twice under arrest and in the face of disciplinary action by school authorities. I feel privileged that I was able to make a small contribution to the progressive social and political movements of my day. If I had graduated high school in the spring of 1968 instead of in 1969, that is probably how I would have remembered my school years.

Then again, as I actually began to write, it became clear to me that over the intervening years I had chosen to remember the late 1960s more for what they could have been and what I had hoped for them to be than for what they actually were. My time in high school was also a traumatic experience in many ways, often grim, and, in the end, demoralizing. I left high school bitter and in a rage, determined to seek personal revenge on a number of authority figures who had made my life miserable. More importantly, I was keenly aware that, when we needed it the most, our movement was losing its always tenuous cohesion, splintering into sectarian factions. When we defined our rebellion primarily by political rather than cultural concerns, winning became of the essence, for high school students no less than for any others. Try as we might, we could not win, either in school or in society at large. Although our movement in the high schools attracted a significant following for several years and achieved some notable tactical victories, it became apparent that our challenge to the school system would be defeated. Short of the success of the broader rebellion in society, it was inevitable that we would lose our struggle. Worse, we could not even pass on the baton to a significant group of younger student activists. As it turned out, continued political activity in the high schools depended to a large extent on a certain political climate and a number of student leaders who were the products of that climate, the majority of whom were about the same age and scheduled to graduate in the same years, 1968 and 1969.

Given the transitional nature of high school, changing political conditions at the end of that decade meant that we could not maintain continuity in our movement and it began to disintegrate in 1970, without effecting any fundamental change. Although it was not clear to us then, the same fate awaited the general groundswell of the 1960s, which subsided several years later. Our cause was no less just and our rebellion no less authentic for our defeat, but a defeat it was. It may be a truism that there is often more to be learned from losing a battle than winning it, but, at the time, I did not know what to conclude from our defeat. It was difficult then to see the way ahead or to know what to do. In turn, the demise of our movement raises the question, beyond the scope of this book, of whether there ever was a possibility of winning, of forcing significant social change.

My story is about a series of related transformations: from childhood to adulthood, from social conformism to rebellion against society, from a non-violent outlook to an attitude that justified any means necessary to win, and from a non-political view of the world to a political view of it. It is a story that begins as a lighthearted protest against authority in elementary school and ends, for the purposes of this book, shortly after my graduation from high school, fresh from several serious altercations with the school administration at Seward and the judicial system. The general context of these transformations is the cultural and political rebellion of the late 1960s in the U.S., which was also a period of turmoil and revolt worldwide. The particular context is defined by the fact that, as a teenager, I still lived at home, under the direct influence of my parents, obligated to defer to their wishes on many questions, simultaneously striving to meet their expectations for me and rebelling against them. It is also a story about my adolescent friendships with several other boys and my relationships with several girls. The vehicle for most of my political education was the so-called “New Left.” The venue was high school, but not the usual high school of parties, proms, sports, and teenage romances, but rather one in which a determined cultural and political rebellion took shape. My narrative is about an insurgency that occurred on many fronts, but in which politics usually assumed first place. It is about how we tried to organize other students and struggled to sort out conflicting political agendas on the left.

The central political event of the latter half of the 1960s was the war in Vietnam. Although opposed to the war in Southeast Asia, in our own way we too were going to war: against an unjust system that we held responsible for Vietnam and other crimes. Developing the outlook of “going to war” is a process, as is learning the mental attitude of being a “good soldier” for the movement. This book seeks to answer the questions of how and why many students like me became political radicals at a relatively young age and why we found our movement so compelling. It is about what some of us imagined at the time to be the early stages of a conflict that we thought would eventually grow into a real war with our social system.

When, as adults, my brother, sister, and I went home to visit our parents, we sometimes traded stories around the dinner table about our trials and tribulations as kids trying to make our way in the world. Over time, we gradually revealed in these discussions the more sensitive and controversial episodes of our youth that we neglected to disclose to our parents when we still lived at home. More than once, my mother and father expressed surprise, and sometimes shock, to hear about things that happened to us that we never discussed before as a family. My parents claimed that my siblings and I had a “secret life” when we were growing up that they knew little or nothing about. The story that follows is part of my secret life, a story, however, not so different from that of many other high school activists in the late 1960s.

If my activist contemporaries are like me, in their late middle age, they alternately rant and rave about the morass of the modern American political scene or descend into silence, frustrated that pressing economic, social, and political problems today do not prompt the large-scale protest movements that we experienced in our youth. We are, in a sense, forever marked by our youthful rebellion, always uncomfortable with the thousand and one accommodations that we have made with a system that we could not radically change or overthrow, even if our view of possible or desirable outcomes of our failed rebellion have changed over the years. Few, if any, of us can look back at the 1960s without some regrets, but a transcendental sense lingers on that our cause was fundamentally just and that we gave an unjust system a run for its money. Without any prospect of a renewal of something like our rebellion of the 1960s on the horizon, I find myself descending into silence. Before that feeling takes over entirely, I want to tell the story of my participation in the high school student movement.

*

Selected Correspondence

February 20, 2008

Dear Eric,

Thanks for the recent installments of Born Witness. I’m out west seeing my eldest daughter, Molly, who has just returned from living abroad for seven years. I look forward to reading your latest stuff when I’m back in Chicago.

I’ve set aside working on my manuscript this month while I take care of some personal stuff, but will get back to it soon. I’m trying to finish a very rough draft of the Teachers’ Strike (Fall, 1968) chapter and the latter part of chapter 6 (Spring, 1968) concerning Erik having his admission to Antioch College withdrawn at Miss Gloster’s request. Did Larsen* ever mention to you that he obtained a complete copy of the correspondence between Gloster and Antioch College when the administration building at Antioch was occupied during a strike in 1972? He’s made copies of all that stuff for me. I must say that it has proven difficult to discipline myself to sit down and write regularly. I’m usually so pooped after work that it’s hard to concentrate on my project. I wish that I had taken some classes on writing in college or graduate school years ago. At the time, all I wanted to do was zero in on the historical subject matter that I was interested in.

I’m glad that I put a lot of effort into tracking down my former classmates, but, unfortunately, it hasn’t proved that fruitful so far for my project. Most people claim to have a very hazy memory of events in high school and didn’t save written materials like I did. I find this strange, because my memories (that I don’t trust entirely) are so vivid. Perhaps I was more invested in our activities than some of my friends, especially from senior year, after you and Erik were gone. Also, Mr Schulich has not responded to my request for an interview. It could be that, in his mid 80s, he’s in bad shape, but I can’t tell because he won’t respond. This is a bummer, since he’s my only shot at hearing our administrators’ side of the story of our rebellion in high school. It also turns out that both Josh Silber and Jane Lifflander are in pretty rough shape personally. It doesn’t sound like life has been very kind to either of them.

I went to see Helen Geltman again in North Carolina. She and I rekindled our romance from high school. We are planning to meet in New York in the spring sometime so I can do some more research in the UFT archive and the main branch of the Public Library. When we figure out a date, I’ll get in touch to see if you and Larsen are available so we can all get together.

Thank you again for your kind words and encouragement on the part of my manuscript that you read. It means a lot to me, especially at this early stage. I sent Erik the same material that I sent you. He called me back about a month ago to say that he liked it but would call again with more detailed comments. So far I haven’t heard from him, but I’m sure that he’s very busy. He had a few memories about sixth grade that I hadn’t remembered, some good off-color stuff about our teacher, Mrs. Sayres. Also, he has photographs of our picket line in front of Seward from April 26,1968.

Please, let’s keep in touch. I’m curious to know how you are planning to put together the installments of Born Witness for a book (I’m assuming that you have a book in mind). How are things going for you otherwise?

Yours, Dave

* * *

March 31, 2008

Dear Eric,

Thanks so much for writing back. I really appreciate your thoughts on my writing project. I have few people with whom I can discuss it and even fewer who are willing to make thoughtful criticism. From day to day, I spend my time worrying about solving construction problems related to my business. Although I lack confidence in my writing abilities, I am convinced that the story is worth telling. For now, at least, I think I’ll skip reading the Oglesby and Sherman books and just keep trying to write out my narrative. Maybe I’ll look at these books later. Sometimes I do feel like the text works itself out in the process of writing. At other times, I’m just at a loss. I’ll try to just keep plugging away.

I spent two years living in the Austrian Tyrol when I was growing up (on my father’s sabbaticals). The second of those two years was immediately before I showed up at Seward. Because they wouldn’t give me credit for attending an Austrian school, I lost a year. That’s why I was a year behind both you and Larsen – we should have been in the same grade. Years later when I returned to finish up college and attend graduate school, I spent another year at the University of Vienna. I studied German and modern Austrian history. My particular interest was in the “Red Vienna” period between 1918 and 1934. The two things that I know the most about in this world are construction and the history of the Austrian Social Democratic Party (ASDP). I don’t know if you know much about this period, but, at the time, it was optimistically viewed as a possible third path to socialism, something between the rank opportunism of the Second International and the totalitarian aspects of the Third International. Some of the Austrian Social Democrats are my heroes, especially certain leaders of the Schutzbund, the military arm of the party. Austria has a checkered history at best, but they can be rightfully proud of the Red Vienna period. Interestingly enough, since two of the major parties trace themselves back to the parties of the period, it is still controversial.

Last week, though, I was just being a tourist. I did however, visit a few of the sites related to the history of the ASDP. I went to the Karl Marx Hof, the housing project where the Schutzbund made their last stand in 1934, and had coffee at the Cafe Central, where the ASDP leadership used to hang out in the evenings and debate policy. I love Vienna. I was pleased to discover that my German was still pretty good, surprising because I’ve had almost no occasion to use it in over twenty years. I managed to make it though the week without a single Austrian offering to help me out in English.

Thanks again for writing back. Let’s keep in touch.

Yours,

Dave

* * *

April 1, 2008

Dear Eric,

The Flak Towers in Vienna are impressive. There are at least four, maybe five, of them spread around Vienna. One of them is actually used for something these days, but the others stand empty. The Viennese would just as soon demolish them, but the concrete is so thick that it’s too much work to break them up with jackhammers and explosives would damage surrounding structures. They’re likely to be there for centuries. Ironically, Vienna wasn’t subjected to that many air raids because it was out of range for most of the war. The Germans would have been better off building them in Berlin. Vienna did get pounded at the end of the war though and the Flak Towers didn’t save them.

We’re on for the Cafe Sabarsky. I’m not familiar with the place. Is it up near where both you and my brother live?

I’m glad to hear that feeling at a loss is a common experience, as it’s my state of mind most of the time. I’m determined to finish my manuscript, however, even if it takes a while.

I’ll send you an update on Susan Steinman as soon as I get more info. I called Dr. Larsen last weekend, but he hasn’t called back yet.

Talk to you soon.

Dave

* * *

April 26, 2008

Dear Eric,

I’ve been worrying about the reliability and accuracy of my memory for events in high school. In the Introduction to my manuscript, which I haven’t shown you yet, I say a few words about memory. A few years ago I read a longitudinal study of memory (comparing what a group of 60 or so adolescents reported about their lives in 1968 to how they remembered their teenage years about 35 years later). The study concluded that it was more or less the flip of the coin whether adults remembered their adolescence accurately. That conclusion was very troubling to me as I was about to start writing an autobiographical manuscript with an even greater time lag between the events and trying to write about my experiences. That study in particular prompted me to redouble my efforts to find documentary material to substantiate my memories and to locate many of my former classmates so that they could confirm, deny, or say otherwise about whether I had gotten the basic historical narrative down correctly.

Of late, I have been reading a number of other studies on memory and my fears have been renewed. I consulted the son of some friends of mine (comrades from the old days) who had just received his PhD in some aspect of studying memory. He says that I’m making a mistake to send my classmates and friends drafts of chapters to read because the act of reading what I’ve written colors their memories. He suggests rather that I should have interviewed them first or presented them with a questionaire to elicit an unbiased response to a long series of questions. It’s not too late to do that with some of my classmates from senior year, but it’s too late, for instance, to do that with you or Dr. Larsen concerning our MLK walkout and student strike.

So, if I can impose on you, I have a few questions: a) Do you feel that you have vivid memories of high school? If so, have you had any of them contradicted by others or your knowledge of historical events of the period? Do you have an opinion about the general reliability and accuracy of memory of the period? When you read my “Walkout and Student Strike” chapter, what was your reaction to it in terms of agreement or conflict with your own memories? Before you read the draft of that chapter, did you first try to conjure up your own memories of the time or did you just start reading it, i.e. “Let’s see what Dave says…” I would very much appreciate your thoughts on this subject.

I hope that you’re doing well. Did you manage to connect with Dr. Larsen? Thanks for the latest installment of Born Witness. I’m worried about what’s going to happen when you finally approach present day–it’s going to screw up my Friday evening routine of reading your stuff.

Take care. Talk to you soon.

Dave

*

* Erik Larsen, MD, was one of David’s closest friends. Prior to our joint activities at Seward Park High School, Sullivan and Larsen had been schoolmates at PS41 – they lived only a block apart – and frequently went camping together. Both of them attended Antioch College.

* * *