Excerpt from Consuelo: An Ofrenda

by Raphael Rubinstein

Guanajuato, Mexico

It was on a Wednesday that my sister Elia died. She was two-and-a-half years old. I was born the next day.

* * *

A death, a birth. An exit, an entrance. Una hija muerta y una hija nacida.

* * *

We were in Pachuca. My parents and my three sisters (soon to be two) had fled Guanajuato where there was too much fighting. Villistas, Carranzistas, Huerta’s Federales. Bandits on the roads, trains in disarray, food scarcer by the day, rifle fire in the streets. It wasn’t safe for anyone, but especially not for people like my father, my blond, blue-eyed, Canadian-Scottish father, even though he had a Mexican wife, Maria Dolores Ulloa, and spoke only Spanish (no longer George, but always Jorge). Señor Jorge Howatt of nueve, Calle de los Desterrados. Not, perhaps, an auspicious name, the street we lived on in Guanajuato. Desterrado: banished, exiled, taken from your land. Years later, the name was changed to Calle Sangre de Cristo, which wasn’t much of an improvement if you had asked us, the anti-clerical Ulloa-Howatts. Well, it turned out that Pachuca—a city with none of Guanajuato’s grace, a city where we knew no one, where we went only because my father could find work there as a mine foreman, wasn’t safe either. Too close to Mexico City, where famine and typhus were raging. They called 1915 “el año del hambre,” the year of hunger. The Revolution was everywhere. Death was everywhere. The day I was born, Obregón and his army reclaimed the capital from Villa and Zapata. It was probably typhus that killed Elia.

Grave of Elia Howatt

One of your children dies, and the next day you give birth to another. Can you imagine what that must have been like for my mother? Driven out of her birthplace by battling armies, traversing a war-torn country with her husband and three young daughters, becoming pregnant in the midst of a bloody revolution, so far from Guanajuato where she had her parents and siblings and friends, barely knowing what would happen tomorrow. What was it like that January of 1915 in Pachuca with one daughter dead but not yet buried as another one was coming out of her body? Which emotion was stronger, grief or joy? My mother’s name was Dolores, which in Spanish means sorrows. That’s certainly what she must have been feeling the day Elia died. And then I arrived. Not a replacement for the dead Elia, but softening the pain just a little, I hope. Or maybe more than a little. La vida es más fuerte que la muerte, ¿verdad? ¿Verdad? I was her consolation, everyone said, the way people will say anything that sounds comforting in the face of tragedy, no matter how hollow and glaringly inadequate the formula sounds, so they gave me a name that paired my birth with Elia’s death, a name that would forever stitch my life to the death of a sister I never knew. Was I really a source of consolation? Fifty-three years later, my mother would lose another daughter, me. Who, if anyone, was her consolation then?

Although things quieted down after the Battle of Celaya, my parents had had enough of fending off violence, starvation and chaos, and my father’s Anglo looks made him a target of anyone who was angry about the complete Yankee takeover of Mexico’s mining industry, and that was a lot of people. Because he was still a British subject thanks to his Canadian birth, he was able to procure British passports for my mother and us three girls. We made it out of Pachuca, traveled through the now Villista-free north and eventually crossed the border into Arizona. When we left Mexico, I was only three, young enough to grow up speaking English without the hint of an accent, which I did, and young enough to grow up without any sentimental attachment to my birthplace, which I didn’t, and which I never wanted to do, ever.

* * *

You probably don’t remember my voice any longer, its timber, its inflections, whether it was low or high, soft or sharp or somewhere in between, and yet its imprint still lingers somewhere in your brain, secreted in a particular neural structure lodged in a rarely visited pathway. My voice, or at least your memory of it, survives even if it is unrecoverable. You retain a trace of how I called your name, how I said Shabbat prayers, how I sang those mournful Mexican ballads to you at bedtime and “The Streets of Laredo.” Sadly, I guess, these elusive traces are the only evidence of what I sounded like. I slipped through life without my voice being captured on audiotape, or my body caught by a movie camera. There is no recording waiting in an obscure archive of me speaking or laughing or singing, and no film of me, not even a few seconds’ worth, walking across a room or attending some civic event. Is anything left of me at all? By now only a dwindling number of people who spoke with me, who heard my voice, who touched me, are still alive. Will you believe me if I tell you that this doesn’t bother me? After all, this is what has happened to nearly every human being who ever lived. We all “go into the dark,” as Eliot, one of my many beloved poets, said. Why should I be an exception, a woman of no great accomplishment? I know that you want to preserve as much as you can of my existence: the few dozen handwritten pages you have of my writing, copies of all the reviews I wrote about Latin American literature, letters and postcards I received or sent, photographs of me taken by persons unknown, the life-sized gold-painted plaster bust of me that my sister made which is sitting in the room where you are writing this, watching over you or maybe just watching you. It delighted you as a child. At Nanny’s house, the one we moved to after my father died, we used it as a doorstop. It was more than heavy enough for that purpose, but it hasn’t been too heavy for you to carry with you all these years, from one home to another.

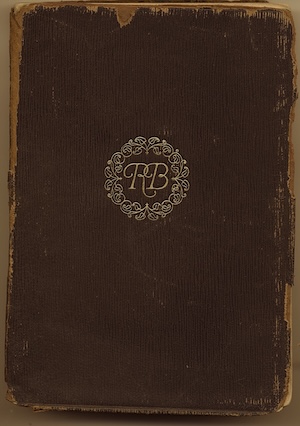

Another relic you’ve kept, something much lighter than that plaster bust, is my copy of Rupert Brooke’s Collected Poems. There it is now in your hands, with its fancy gold design embossed into cheap leather covers that are slowly crumbling away at their edges. You know it’s mine because on the flyleaf with its cottony green and blue speckling I wrote, in my neatest hand, as if the letters were floating in a cloud-dotted sky: “Consuelo Ulloa Howatt January 28, 1929.” It was my 14th birthday. Knowing how much I loved poetry, my sisters gave me this book as a present. We were living in Ray then. Father was a foreman at one of the town’s copper mines. It had been nearly ten years since we left Mexico. I wonder, does the book still have a piece of torn-off brown paper slipped between pages 28 and 29, just before the poem “Pine Trees and the Sky: Evening,” on which I copied out two poems about Brooke? And that newspaper clipping about the monument to Brooke erected near his grave on the island of Skyros, and a sonnet to him by Mary Ballard?

Consuelo Ulloa Howatt

Next to the poem “The Jolly Company” are a few words I wrote out in Spanish from José Asunción Silva’s poem “Estrellas que entre lo sombrío”: “¿Por qué os calláis si estáis vivas/Y por qué alumbráis si estáis muertas?” which you have figured out mean something like “Why do you stay silent if you are alive/And why do you shine if you are dead?” That’s a good question, no? And not just to the stars. Can something, someone, be dead and yet speak? And can illumination from some body long since extinguished nonetheless reach us?

Silva died at the age of 30, by his own hand, a bullet through the heart. He was despondent over the death of his beloved sister Elvira and anguished that most of his unpublished writing, including the novel he had just completed, had been lost in a shipwreck.

If I had lived a few years longer, perhaps I would have told you about my love for José Asunción Silva, and my other early passions like Rubén Darío and Amado Nervo, and I would have read their poems aloud to you in Spanish, and you would have grown up with a head full of modernismo. But would I have tried to interest you in Rupert Brooke? Did I still love his poetry by the time I became a mother or had I long since dismissed it as an adolescent passion? To tell the truth, nearly all traces of poetry, not just Rupert Brooke’s, had drained out of my life by the time my marriage to your father began falling apart.

Years: 1915: my birth and Rupert Brooke’s death; 1929: the year I was given his Collected Poems; 1931: the year the monument to Brooke on Skyros was unveiled, which was also the year that my father died. Brooke’s memorial was unveiled on May 4. My father George/Jorge Alfred Howatt died June 28. Was he already ill as I read about the memorial to Brooke and clipped that article? Was I thinking about my father’s mortality as I let myself be flooded with sadness at the memory of a dead English poet?

* * *

What was it like, you are wondering, to be reading Rupert Brooke, “the handsomest young man in England” Yeats called him, in a dusty Arizona mining town around 1930? A 14-year-old girl in love with literature, stuck in a stony, treeless landscape, in a town of quickly-built three-room company houses, walking along dirt roads, playing in a dirt schoolyard, living in the shadows of those giant angular structures straddling mine entrances like vultures, looking up at stark rocky mountains, walking over hills where the earth cracked open because so much copper ore had been dug out from underneath, a naked, ramshackle town with one 12-room hotel and one movie theater and a railroad line to cart away thousands of tons of ore a day, much of it clawed out by Mexican miners, who were paid half of what the Anglos got, and when the mining industry suffered one of its periodic collapses, government-sponsored trains would arrive to haul them in box cars back to the border. You imagine me in one of those company houses, sharing a room with a couple of my sisters, helping my mother in the kitchen, a woman who when she lived in Mexico had never cooked a meal in her life and was now feeding a family uprooted from their home in Guanajuato, the most beautiful city in all of Mexico, wondering why fate and revolution and her choice of husband had brought her to such a desolate, cultureless, ugly place, not that she had much time to think such thoughts, four daughters to raise, a new language to do daily battle with, a husband who too often had to descend into those deep caverns of sweat, smoke and death.

Consuelo Howatt’s copy of Rupert Brooke, The Collected Poems, 1928.

Brooke’s poem “Pine Trees and the Sky” opens with a scene that couldn’t be more removed from the arid desolation of Ray: “I’d watched the sorrow of the evening sky,/And smelt the sea, and earth, and the warm clover/And heard the waves, and the seagull’s mocking cry.” One fact of my fate, perhaps minor, is that I was destined never to live on a coast. My life, after leaving Mexico, would be passed in Arizona, then Kansas, then Arizona again. I’d only have the chance to hear waves and the cries of seagulls briefly, now and then, before returning to one of my landlocked homes. You, my child, after I was dead, would be luckier: living in San Francisco, a city I loved, and New York. Imagine me, then, with this book you are holding in your 65-year-old hands resting in my 14-year-old hands as, sitting by the window looking out onto the bleak environs of Ray, I dream of clover and the sea.

For the most part, the children of Mexican miners weren’t allowed to attend school in Ray. Instead, they went to school a mile away in Sonora, a town built for solely for Mexicans. Despite my and my mother’s place of birth, I wasn’t considered Mexican; my father’s Anglo genes trumped my mother’s Hispanic ones. Because our skin color was pale enough to pass, my sisters and I didn’t have to trek to Sonora for school. All the same, the list of names in my tiny graduating high school class (1931) wasn’t purely Anglo: Gilbert C. Brown, Moses Brown Jr., William Brown, Bertha M. Bruce, Joe G, Ferris, Jr., Alice D. Garcia, Consuelo Ulloa Howatt, Selma Elizabeth King, Elizabeth E. Kumke, Sabino Lozano, Jesus L. Miranda, Gladys V. McBride, Constance Mary Owens, Joe Vera.

In 1930, the Arizona Labor Journal warned against “further Mexicanization of the Southwest.” White Americans in the region, it declared, were suffering due to “the permanent addition to our population of a great mass of the least intelligent and the least assimilable of all the alien groups which have settled among us.”

The U.S. census of 1930 shows me living in Ray with my father, mother and little sister Doris. (My older sisters, Isabelle and Gloria, had already left for college.) One of the 32 columns on the census form is for “Color or Race.” My father gets a “W” for White. My mother’s entry is a little hard to decipher. It looks like the census taker first wrote a “W” and then changed it to “M” for Mexican. Doris and I both get an “M.” Well, if the U.S. government didn’t consider me “White,” I was perfectly happy to be “Mexican.” In fact, as the years went by, I preferred it. I was almost disappointed when they dropped “Mexican” as an option for “Race or Color” in the 1940 census. I say “almost” because I knew it stung for others who had to face worse discrimination than me.

I can’t help wondering what lay behind the mixed-up letters after my mother’s name. Did the census taker look at her and write “W” which was then changed to “M” when her birthplace became clear? Or did my mother declare herself “White” only to be contradicted by the census official? Or did she misunderstand the question? The truth is, her English was never very good.

W and M are upside-down versions of each other. Could the same thing be said of “Whites” and “Mexicans”?

The same year that I was given my copy of Rupert Brooke’s poems, the U.S. Secretary of Labor, one James J. Davis, lamented that “the Mexican people are of such a mixed stock and individuals have such a limited knowledge of their racial composition that it would be impossible for the most learned and experienced ethnologist or anthropologist to classify or determine their racial origin.”

Shall we try to determine mine? You’ve seen a photo of my maternal great grandparents Clemente Ulloa and Maxima Muñoz. On a scale of 1 to 10, how “indigenous” do you think they look, 1 being the least, 10 the most? (I’d say 8 or 9 for him, 2 or 3 for her.) Octavio Paz said that the Mexican doesn’t want to be either an Indian or a Spaniard, “nor does he want to be descended from them. He denies them. And he does not affirm himself as a mixture, but rather as an abstraction: he is man. He becomes the son of Nothingness.” What would that be in Spanish? Hijo de nada? Paz was probably reading too much Sartre, just as James J. Davis was probably reading too much Madison Grant. Actually, to read Madison Grant at all is to read too much.

* * *

A girl stood on the hill, and the wind blew in her mouth although she wished to die.

* * *

We grew up, me and the two of my sisters who had also been born in Mexico, with nostalgia for a place we could barely remember. Even after crossing the border we lived in houses where every object’s real name was its Spanish one; from our mother we were infected with a deep affection for the city of Guanajuato and for our relatives who still lived there; it was as if we were residing not in the arid furnace of Ray or, later, amid the flat streets and squat, yard-ringed houses of Tucson but, instead, still wandered through Guanajuato’s tangle of narrow alleyways and churrigueresque churches, relishing the achingly picturesque views from its densely packed hills, mused among the monumental ruins of the derelict silver mines that had made it the richest mining city in the entire world, stood transfixed before the wall of tin retablos in the Iglesia de los Mineros, admired the neo-classical Teatro Juárez where our grandfather had recited his poetry for civic occasions, strolled around the elegant Presa de la Olla, a dam and reservoir constructed in the 18th century and a favorite site for weekend outings. The most beautiful city in Mexico, everyone said. Whenever we returned to visit, it always lived up to every memory, real or imagined. Our pride came from being Guanajuateñas as much as from being Mexican.

“Guanajuato, tierra de mis amores,” as the popular song has it:

Tierra de mis amores y mis quereres,

Donde viví feliz mi juventud,

Siempre te guardaré en mi pensamiento,

Un recuerdo de amor y gratitud.

Land of my loves and my wants

Where I happily lived my youth,

You will always be in my thoughts

A memory of love and gratitude.

One day, long after I had finished my time among the living, some person or persons unknown stole the bronze bust of the song’s composer, Jesús “Cucho” Elizarrarás Farías, from the Jardín del Cantador, the lovely 19th-century park in the center of Guanajuato. They also defaced other busts of prominent Guanajuateños, including the writer Jorge Ibargüengoitia, that stood nearby. This attack on the city’s cultural heritage is upsetting to me, even though I know that the disappearance of a hunk of metal or the scrawling of some obscene graffiti, minor victimless crimes, are barely worth noting at a time when, a century after we left Mexico, the State of Guanajuato has become the most violent part of that violent country:

Cartel battles stun once-peaceful state of Guanajuato, Mexico

Mexican cartel war transforms Guanajuato into a deadly place

9 Killed in attack on wake in Mexico’s Guanajuato State

Guanajuato: Tourist mecca turned to killing field

Cartel hunts down, kills Guanajuato police in their homes

Pregnant woman has hands amputated by Mexican drug cartel in Silao, Guanajuato

But what do such horrors matter to you and me, to a ghost and her amanuensis?

Mi Guanajuato, yo solamente quiero

Un rinconcito para descansar en él.

My Guanajuato, I only want

A little corner to rest in.

Facade of the Teatro Juárez

Author’s note: The subject of Consuela: An Ofrenda, the source of this excerpt, is the life of my mother Consuelo Ulloa Howatt. Born in Mexico, as a young girl she came to the United States. with her family, fleeing the violence of the Mexican Revolution. She was given the name Consuelo (consolation) because she was born the day after the death of her two-year-old sister, a victim of Mexico’s chaos. I have written in my mother’s own voice (addressed to me, at once her son and the author of the book). I draw on various literary forms: memoir, fiction, poetry, biography, as well as incorporating archival material, in an attempt to reconstruct one woman’s life, with all its disappointments and failures, its passions and its revelations. At the core of the book is my mother’s relation to her Mexican identity, which was central to her life.

Photo Credits: Jorge Gardner, Guanajuato, Mexico; Gill Rifaat, grave of Elia Howatt; all other images from the collection of the author

***