A Personal Reflection on Dance Division Fellows Project, Jan Schmidt

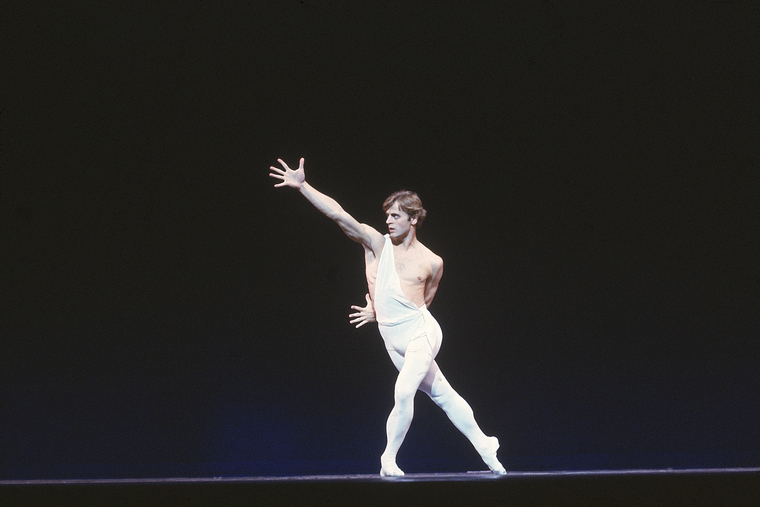

If you’re in a gathering of folks who don’t know much about dance and you want to name a dancer they might have heard of, whose name do you invoke? Misha? Yes. Mikhail Baryshnikov, star of stage, film, television; a dancer who thrilled audiences whether he performed classical Russian ballet or modern, post-modern, tap, jazz, even hip-hop. Naturalized citizen of the United States, born in Latvia, the principal dancer of Kirov Ballet, he left Soviet life behind when in 1974, at age twenty-six, on tour with the Bolshoi Ballet, he was granted political asylum in Toronto. It’s said he hated the word defector, though you can’t find a documentary, magazine, or news article that doesn’t refer to his “defecting.” Dictionary synonyms: “deserter, traitor, renegade, rebel, insurgent, apostate, revolutionary, or turncoat”—none of which apply to him, except maybe rebel. An artist, he wanted to expand his personal freedom, his artistic opportunity, his repertoire, and his sense of self.

After a short stay in Canada, he came to the United States, immediately distinguishing himself as a dancer in classical ballet, while exploring other genres. Within two years he was working with New York City Ballet. He went on to dance with American Ballet Theatre, becoming their artistic director in 1980. As Baryshnikov worked with a greater variety of choreographers, he proved his ability to transcend style. He also starred in films including Turning Point (1977) and White Nights (1985), made numerous appearances on television, notably as love interest for Carrie Bradshaw in Sex and the City, and in the theater on Broadway. He also founded the Baryshnikov Dance Foundation and the White Oak Dance Project with choreographer Mark Morris, opened the Baryshnikov Arts Center in 2005, and in 2009 published a book of his photographs, Mikhail Baryshnikov: Merce My Way. Always transforming himself, growing, redefining himself, for himself, for us.

In 2011, at 63, an age when people begin looking back at their lives, Baryshnikov donated his collection to The Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center. As curator of the Dance Division, I was thrilled to receive this collection of hundreds of videotapes and numerous boxes of press materials, photographs, programs, scrapbooks, and touring documentation.

About a month after these arrived at the Dance Division, one of his staff members called to say Baryshnikov had found a stash of 8mm films he wanted to add to the donation. I excitedly agreed that we would take them. The day and time the films were due to arrive, I hustled from the third-floor research center to the Amsterdam entrance with another staff member and a cart. As I got to the large glass doors, I saw Baryshnikov’s car pull up. The man himself emerged and removed a box from the trunk. As the guard buzzed the door open, I rushed to take the box out of his hands—how could I permit Baryshnikov, artist, donor, larger-than-life human being, to carry his own box of film? As I tried to yank it from him, he held on, and we had a little tug-of-war until he gently allowed me to take it, giving me his sly, half-smile in recognition of the oddness of the moment. While I put the box on the cart, he brought another one out of the trunk, put it on the cart himself, waved, and drove off. As I wheeled the cart to the elevator for the third-floor, his smile stayed with me. It seemed that he had seen me with great clarity, as though I were a character in a piece of choreography that he’d immediately understood in some direct, somatic way.

Turned out those cartons held over 160 8mm films, many that depicted Baryshnikov and his peers in the theater and classrooms of the Vaganova Academy, in what was then Leningrad. The films were added to his archive and, in just over two years, with thanks to grants from generous donors, the Dance Division was able to preserve, catalog, and make this extraordinary material available to the public.

The range of the Dance Division’s archive is enormous and varied, encompassing modern, post-modern, classical, and traditional dance from all over, such as our Cambodian Interview Project, the Bhutan Data Base, and African Dance programs.

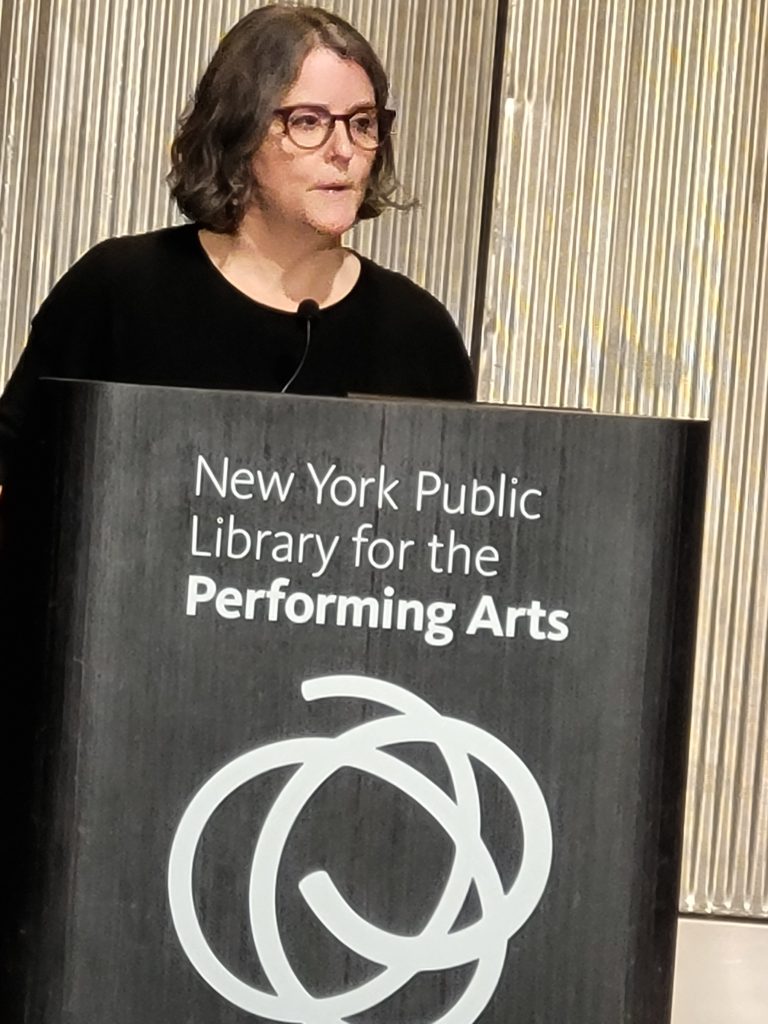

I am proud to say one of the programs instituted when I was curator, and continuing today, is the Dance Research Fellows. Begun in 2015, in these past nine years, it has supported researchers in their efforts to study dance subjects spanning the genres, countries, and artists from many time periods. Some years the applicants pick their subject, other years, they are asked to do research in only one area. It was gratifying to see that the Fellowship has continued under the watch of Linda Murray, the present curator, a woman who is expanding the scope and possibilities of the archives. Like Misha, she is always searching for more possibilities, openings, and ideas.

When I learned the 2024 Fellows were to study the materials in the Mikhail Baryshnikov Archive, I practically grand jetéd around my apartment. Unlike most of the previous individuals whose lives and works were studied, he was a living artist and a dancer rather than a choreographer, but what so excited me was seeing, nine years after I retired, the convergence of two things I was most proud of during my career: thee acquisition of the Baryshnikov Archive and the creation of the Fellows project.

As in past, the Dance Division held a public symposium on the Fellows’ findings after their year of study. This event becomes a space for dancers, choreographers, writers, critics, and aficionados to gather and feel a part of the dance community. So, it was with great delight and anticipation that this past January 31, 2025, I joined the symposium audience at ten in the morning in the Bruno Walter Auditorium. The house was packed. Glancing around, I saw many important dance writers in the audience including Robert Greskovic, Nancy Dalva, Lynn Garafola, among so many others.

The first presenter was Marina Harss whose vivid, poetic dance writing has appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, Dance Magazine, to name a few. Her recent book, The Boy From Kyiv, is a biography of the choreographer Alexei Ratmansky, another emigre. For her presentation “An Extraordinary Transformation”—Mikhail Baryshnikov at New York City Ballet, the core of her talk about Baryshnikov’s early years in the United States centered on his sense of identity, of self, especially as an immigrant, as was his mentor Balanchine, born in Russia.

Harss’ program notes begin with a quote from Baryshnikov at the beginning of David Gordon’s Made in USA from “Dance in America” 1987. “I did all there was to do, I wanted to do more, more was somewhere else, so I went.” She asks the question, “How has dislocation shaped the artist each of them became or is still in the process of becoming?”

In talking about how Baryshnikov’s search for artistic freedom as he absorbed these new cultures and friendships, Harss quoted a John Gruen article from July of 1974, in which Baryshnikov spoke through an interpreter. “When a dancer has such fantastic schooling…most likely he will go through a period where he wants to seek his own identity…. He feels, this is what I must do. I feel I must act in this way, even if it might be a mistake. I must try this certain style which differs from the other styles I have danced before…. If this kind of opportunity does not arise within the system, then you kill your own talent.”

Ferocious words, “kill your own talent.” What kind of country puts a lock-down on freedom to explore your talent? I’m afraid we’re about to find out in the United States.

In speaking of the Baryshnikov’s taking on more styles with this new freedom, Harss said of Balanchine’s “Rubies,” which Baryshnikov danced with Heather Watts, “The choreography is twisted, jazzy, and rife with references to sport as well as to popular dance forms like the tango, the Charleston, and Spanish zapateado.” Then she screened an excerpt from a 1979 televised performance at the White House during Jimmy Carter’s presidency. She added a quote from the critic Robert Greskovic, who wrote after watching Baryshnikov dance Rubies, “Dancing Balanchine is not a process of application or addition so much as it’s a momentarily meaningful state of being.” (Italics mine.)

As she showed more clips, we in the audience thrilled seeing Baryshnikov’s virtuosity, sensational leaps, fast turns, and modern dance expression. In the excerpt of Balanchine’s “Theme and Variations” from 1976 with Gelsey Kirkland, Harss said, with Baryshnikov dancing it, this work had “the sense of almost spiritual nobility with which he imbues his performance. There is nothing extra, just the purest dancing.”

As a finale, Harss talked about Baryshnikov’s relationship with another emigre, Alexei Ratmansky, Russian-Ukrainian-American who came to New York City in 2009 after almost five years as director of the Bolshoi Ballet. Soon after arriving here, he choreographed a solo for Baryshnikov. When Harss screened this clip of “Valse-Fantaisie,” she said that this ballet was “about memory and about Russianness.” She added that when she saw this in 2009, “It was as if time had collapsed, and Balanchine, Baryshnikov, and Ratmansky had found themselves in the same room, together. All three had left home for good, taking their past, their memories, and their schooling with them, like a suitcase full of treasures. All three had used the contents of that suitcase, not as relics to be sealed in a time capsule, but as the foundation for something new.”

Memories. Relics. Archives. Identity. Yeah, words for thought. Baryshnikov knew he was on a path, but—as it is for all of us—he had no idea where it was leading. Every new style took him to a place he hadn’t been before. Choreography is the pathway on the search for form in dancing. Like writing, like life, it begins in the moment, then a new way of seeing and hearing as we advance without a clue as where it’s taking us. We trudge this path without a map, then, as the decades pile up, one can look backwards and begin to see the path, the form.

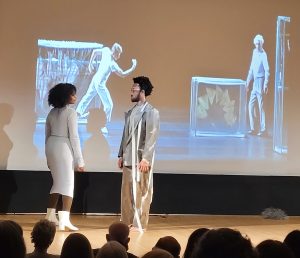

Next on the program, interdisciplinary artist, Marcelline Mandeng Nken, from Yaoundé, Cameroun chose to create a dance work with video art. In the first section, in front of the video projection of photos from the archive of very young Misha, her dancer Raymond Pinto circled and twirled with a hand-held light under his tulle skirt in an ever-surprising movement piece inspired by Nken’s work at the Library. Her presentation, “Queening The Knight: Baryshnikov’s Vulnerability and Masculinity On Display” wove these elements together in a study of Baryshnikov from another angle. She wrote in her program notes: “The work mythologizes the dance legacy of Baryshnikov, pairing his ephemera with archetype of Janus, the two-faced Roman god of gate and doorways, as a device for nonlinear storytelling. . . . A series of dualities emerge at the membrane where the two characters meet to create a mosaic portrait of Baryshnikov as a dancer and an artistic director.” The juxtaposition of her photo collage video with Raymond Pinto dancing before those images was fascinating, but her last section really nailed the duality concept. The projected clip came from a film of “Occasion Piece,” with Mikhail Baryshnikov and Merce Cunningham and a set by Jasper Johns. The film of this stunning “duet” between Merce and Misha, each performing separate solos, not interacting, yet somehow communicating, as 80-year-old Merce, laying his hand lightly on a barre hidden by the set, moves his arm or shoulder in tiny expressive movements while Baryshnikov flits among the boxes in the glory of youth. On the Bruno Walter stage, with that duet projected behind them, Mandeng Nken and Pinto performed their own suggestive and evocative duet. A vision within a vision, multiple personalities combining various choreographies to create a new way of being—the many faces of Baryshnikov.

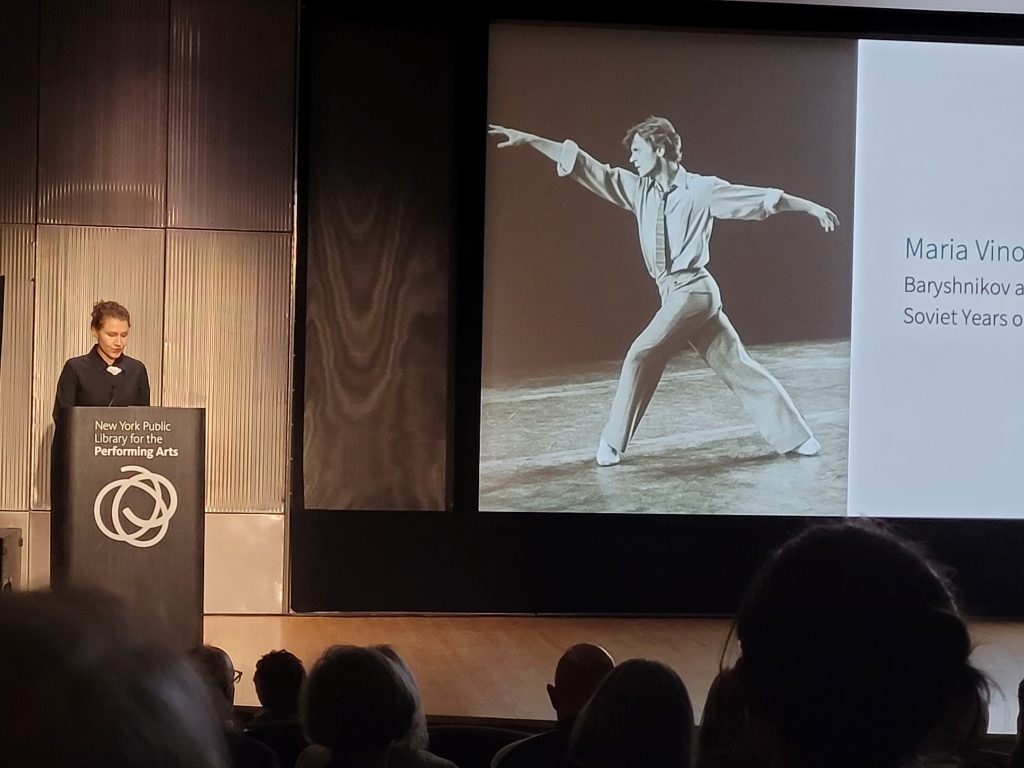

Maria Vinogradova, the third Fellow to present, screened clips from that boxes of films that Baryshnikov and I once tussled over. Her “Baryshnikov and the Kirov Cohort: Their Soviet Years on 8mm Film,” contained amazing footage of dance classes from the late 1960s to early 1970s, one featuring a young Misha sprinkling water on the floor to prevent dancers from slipping. These days people have huge supplies of video from their youth, but videos from that era are rare, so these miracles from the past have a fascination of their own. Earlier we had the pleasure to witness Baryshnikov as the legendary star, performing miraculous leaps and pirouettes with sensitive, nuanced expression, then in a jump cut, watch him perform the trainee function of sprinkling water.

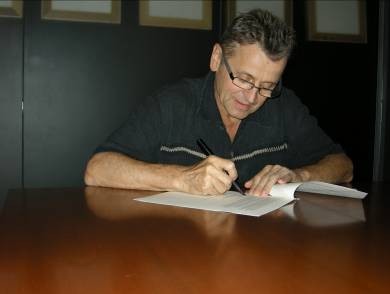

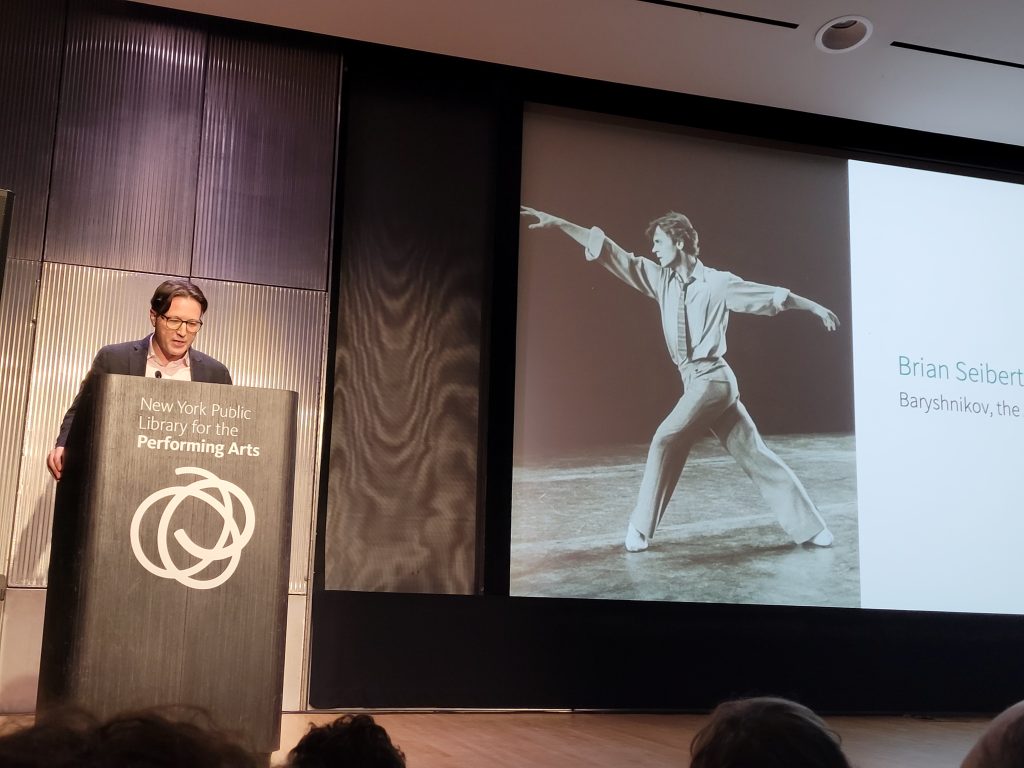

Brian Siebert, features writer for The New York Times, teacher at Yale University and author of What the Eye Hears: A History of Tap Dancing,presented his section, “Baryshnikov, the American Dancer.” In discussing Baryshnikov’s process for learning other forms of dance and being “American,” Siebert mentioned he did this partly by watching films, including Guys and Dolls (1955) with Brando and Sinatra, saying how much Baryshnikov loved the gangster look and that he was captivated by Fred Astaire and his smooth, cool persona. Siebert screened a dance excerpt from White Nights (1985) with Gregory Hines and Baryshnikov. In the film, the solos demonstrated their different styles, Hines jazzy free-form tap and Baryshnikov’s improvised ballet, but during their duets the chemistry between them was palpable. Weaving throughout his presentation, Siebert showed interview clips of Baryshnikov. When Baryshnikov first learned tap dancing, he said, “I hear myself dance. I never heard myself dancing before.” Siebert showed a comic skit from Bob Hope in China, telecast on WNBC-TV in 1979, with Baryshnikov and Hope joking with each other. Hope says he heard Fred Astaire was his favorite dancer. Baryshnikov agrees and Hope challenges him to a tap contest. With his sly, half-smile, Misha copied Bob Hope’s easy, soft-shoe steps.

That look. Suddenly I was on the elevator with Misha again. This was before his archive came to the Dance Division. While the Library’s attorneys were still struggling with Baryshnikov attorneys about contract language, I attended an event at the Baryshnikov Arts Center. As he entered the elevator, I smiled and, worried that he might not recognize me outside my usual Library context, said, “Hi, I’m Jan Schmidt, Curator for the Dance Division.

He nodded, said, “I know who you are.”

I told him how much we were looking forward to his collection coming to the Library.

He looked at me questioningly and said “I have no idea what you’re talking about.”

My face must have told the terrible story going on in my head: I’d mixed everything up: I sucked at my curatorial job and I was going down in a fiery blaze of humiliation and failure. I was the outsider, traitor, renegade, apostate, defector of self. Or just plain defective. He must have read all this, because, as he stepped out of the elevator, he turned, gave me that same sly, half-smile and said cheerfully, “I’m happy to be donating to the Dance Division.” I have no idea what my face did, but I nearly fainted with relief—he’d been messing with me. And I was elated—Misha had joked with me.

I returned to the audience from memory land as Siebert screened a section from the 1976 duet in Ailey’s Pas de Duke. A mere two years into his new, post-Soviet life in New York City, Baryshnikov performed with statuesque star dancer Judith Jamison. Having these two phenomenal dancers spinning and kicking in an astonishing balance to the complex intertwining of classical ballet, jazz, and modern dance was a sensational way to view Baryshnikov’s range and to lead the audience to feel connected to his search for identity through dancing.

Though I was unable to stay for the Fellowship presentations by Alessandra Nicifero andJordan Demetrius Lloyd, I trust they were as extraordinary and revelatory of Baryshnikov’s evolution as the first four had been. Nor could I attend the Dance Division’s party, held after the after the symposium’s conclusion, celebrating the Fellows’ work and their remarkable subject. In truth, I was heartbroken to miss the opportunity to tell the Fellows how terrific they were and to thank Misha for the donation of his archive to the Library. I would have loved, too, to congratulate the staff at the Library, in particular to Daisy Pommer, Original Documentations Producer, and Linda Murray, Curator.

But even as I mourned missing this celebration, I recalled another party from the days when I was curator and Baryshnikov’s materials had just arrived at the Dance Division. The Library’s administration “suggested” we organize an exhibition with a gala opening. Usually, an exhibition is curated by examining all the cataloged materials. This time, with nothing cataloged, we had to root through boxes and perform a preliminary examination of the archive, to pull out items to be featured in the exhibit. In less than four months, we put up an exhibition in the Performing Arts Library’s Oenslager Gallery. Items included in the display cases were a yearbook from 1967; notes from Frank Sinatra, Jerome Robbins, Fred Astaire, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Robert Wilson, Kirk Douglas, Merce Cunningham; and Lincoln Kirstein. Videos and photographs were projected on the back wall screens.

This grant event, to be held on November 1, 2011, was hosted by Anne Bass and Carline Cronson of the Friends of the Jerome Robbins Dance Division. Numerous donors, Library trustees and administrators, major newspaper and dance press reporters, as well as dancers and choreographers were all invited. Trying to coordinate all these elements while we put on an exhibition, was one of the most harrying, yet exciting times in my career, as it must have been for my colleagues.

Then, a few days before the celebration, Misha’s wife Lisa Rinehart called. Misha had just learned that he was a recipient of the 2011 Mayor’s Award for Arts and Culture and was to be honored in a ceremony at the exact same date and time as our event.

What? I gulped and laughed hysterically. “So you’re saying Misha won’t be at his opening?

Incredulous, Lisa said, “You’re laughing?”

I had no words. I was already imagining my conversations with the President of The New York Public Library, the Trustees, Allen Greenberg of the Jerome Robbins Foundation, the Friends of the Dance Division, Anne Bass and Caroline Cronson, who were hosting the gala. Telling one and all, “Ah, just a little issue: Baryshnikov can’t make it.”

Lisa called back the next day: Misha might be able to make it after all. The mayor’s event was also at Lincoln Center and Baryshnikov could rush to our event right after.

Though somewhat relieved, my tension stayed ratcheted up in my bones. How long would the mayor’s program actually last? That night, as the Gallery filled with chatting, champagne drinking guests, I glanced at Tony Marx, President of the Library, Kate D. Levin, Commissioner of the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, Anne Bass*, Caroline Cronson, Jacques d’Amboise, Mark Morris, Allen Greenberg, and the other major players, who seemed to be enjoying the exhibition, wondering how they’d feel when Misha didn’t show. As the time for the speeches neared, my nerves began to vibrate. I heard a friend’s voice saying, “You can’t outrun death, but you can outrun fear.” I quieted down and surrendered to whatever might happen.

A moment later, Misha pushed open the door at the Lincoln Center Plaza entrance. Accompanied by Lisa and his retinue, he came in as though casually making a late entrance—hardly as though he had been, moments before, heaped with honors by the mayor. Immediately people surrounded him and he began greeting one and all and I was saved. Again, I received that wry smile. I was in too much shock to take in much of what happened afterward, but when I look back, it clearly was a great success.

As was the 2025 Fellows’ symposium at which Misha’s work—and process—was honored in a different way, by some of the most important living dance writers, scholars, and performers. A famous Baryshnikov quote continues to reverberate with me: “I do not try to dance better than anyone else. I only try to dance better than myself.” In his search for self, he is our mirror and we become him as he flies across the stage, in search of ourselves, of our own identities. None of us defectors. All of us, more or less recently, immigrants.

Like complex choreography that weaves multiple styles and elements, the Jerome Robbins Dance Division’s programs deliver a dynamic array of genres and artists to a talented audience of writers, dancers, choreographers and critics. The Library has created a space in which to demonstrate the importance of art, writing, dance, and, by example, the power of archives and libraries to connect us to who we are.

These days, when torrents of rage and anger often stream in my veins with no outlet, I call to mind how it felt to sit among the members of this esteemed audience and to be a part of the community of the body and spirit. After each Fellow’s presentation, and often during them, as some extraordinary moment of dance, music or words caught us by surprise, we clapped and roared our appreciation—uplifted by Baryshnikov’s ongoing search, and by extension, affirmed on our path toward realizing our most expressive, courageous selves.

* * *

The recording of the symposium is available for onsite viewing. You can make an appointment to watch it by emailing dance@nypl.org.

The next application cycle of Dance Research Fellowships will be announced later this spring.

Link to Mikhail Baryshnikov video archive https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/mikhail-baryshnikov-video-archive#/?tab=filter

*Anne H. Bass, dear friend of the Dance Division, passed on April 1, 2020. She worked closely with the Dance Division on many projects including support for the preserving and cataloging the Baryshnikov Archive and the Exhibition and Gala to celebrate the collection. After her passing, she endowed the curator’s position, so Linda Murry’s title is now the Anne H. Bass Curator, Jerome Robbins Dance Division.

* * *