An Interview with Peter Glassgold, creator of collaged “Englishings” of the poems from Boethius’ On the Consolaton of Philosophy

Introduction

In 1987, the writer and translator Peter Glassgold began collecting English translations of On the Consolation of Philosophy, a hybrid work of prose and poetry written in Latin by Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius (c.480–524 AD). Boethius was a man of letters and advisor to the king of Italy’s Ostrogothic Empire, Theodoric the Great. After whistleblowing at the king’s court, Boethius was imprisoned for treason, tortured, and finally executed. He wrote the Consolation while incarcerated, an act of dignity at a time of trial. Over the centuries, English translators of the work have included Chaucer, Alfred the Great, Queen Elizabeth the First, and multiple modern translators such as H.R. James (1897) and David Slavitt (2010), among others.

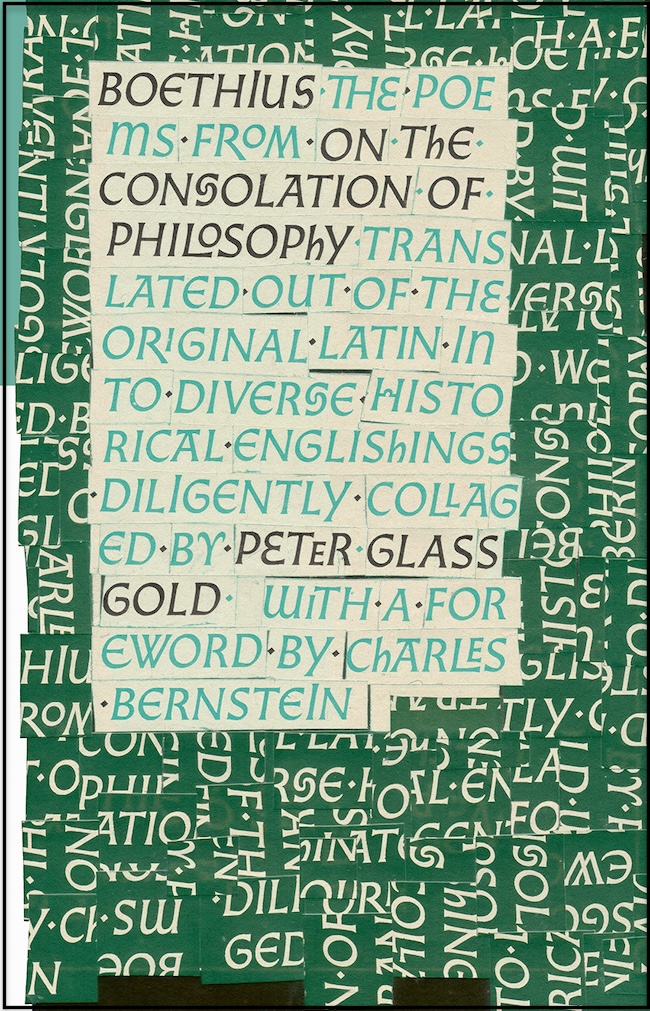

Surveying the various “Englishings” of the Consolation, Glassgold embarked on the project of translation of the poems from the book as an historial, diachronic sound collage. Glassgold allowed the tones and word-work of Old, Middle, and Modern English versions to inform his translations, molding them into playful, evocative poetic inventions. The result was Boethius: On the Consolation of Philosophy, with the subtitle, “Translated Out of the Original Latin into Diverse Historical Englishings, Diligently Collaged by Peter Glassgold.” First published in 1994, this unique book has been reissued in 2024 by World Poetry Books, the imprint of long-time friend of Cable Street, Matvei Yankelevich, whose own work appears in this issue. The reissue has a rolicking forward by Charles Bernstein. Our review of the book can be found here.

Cable Street’s consulting poetry editor, Dana Delibovi, interviewed Glassgold about his book and his innovative method of translation.

Interview With Peter Glassgold

DANA DELIBOVI

What drew you to Boethius? What aspects of his writing or character have most intrigued you?

PETER GLASSGOLD

It was circumstance and language that brought Boethius to my attention. This was back in 1987. My wife and I were living temporarily in a sublet apartment in Brooklyn while our own apartment nearby was being renovated. We were removed from the familiar objects of our life, largely living out of cartons, away from the comfort of our bookshelves, confined to reading only what we’d brought with us. I was also a writer between books, a hard place for me to be. I’d recently finished one, the typescript now safe in its publisher’s hands, and was mentally cruising around for another. I happened at the time to be reading Chaucer’s Boece, his own (prose) translation—into Middle English—of Boethius’ On the Consolation of Philosophy, and realized that many years before I’d read excerpts of this same Latin work as translated into Old English (i.e., Anglo-Saxon) by King Alfred the Great. Still another and later translator, as I now learned, was Elizabeth I, turning it into ur-Elizabethan English.

Our lives in the temporary sublet, of course, were not in danger. We were not in prison, like Boethius, and about to be tortured to death, but I empathized with his lonesome condition, and it came to mind that when we got back home I’d look a little deeper into the question of Boethian translations into English. The seeds for my collage translations were planted.

Regarding Boethius’ writing, I’m not a professional classicist and can’t tell you how well or badly his Latin style stacks up against earlier writers in the language (who were themselves a pretty mixed bunch, like all writers in any language). But as to his character, it was clearly strong. He was a man of principle who maintained his integrity in trying and troubled times and died an innocent man, his dignity intact until the end.

DELIBOVI

Boethius always struck me as an outlier in his time and place—an historically and stylistically unique writer. Do you agree, or do you think Boethius is an integral part of a tradition? What is his literary and philosophical context? Who were his classical and contemporary influences?

GLASSGOLD

Boethius was not so much an outlier, I think, as a man betwixt and between, caught on the bridge between classical Greek and Roman philosophies and poetries, in their myriad styles, and Medieval scholasticism; between the fallen Roman empire of the West (now ruled by a Germanic king) and the strong Roman empire of the East.

I’m no authority on late Rome and the early so-called Dark Ages of the West, but in my personal opinion, Boethius strikes me as both a preserver and a synthesist. He was, after all, a Christian who respected and admired the writings of pagan authors, a Neoplatonist who translated all of Aristotle’s known works into Latin. In other words, he was an intellectual—not an easy thing for a minister of state to be in any time or place, or anyone else for that matter.

DELIBOVI

Your book translates from the original Latin of On the Consolation of Philosophy into “collaged” English, using past translations in older forms of our language. Charles Bernstein, in the Foreword to your book, calls this process “pataquerical.” Can you describe the process and the reasons you chose it.

GLASSGOLD

The words I used for my translations were not, in fact, picked up directly from earlier translators, but their work gave me entrée into the English of their time. That is to say, the words in my Boethius were of my own choosing.

In any one line, I ranged through the whole known vocabulary of English, from Old to Modern. Charles Bernstein’s “pataquerical” is a critical word of his own devising, a good one too, covering the mostly overlooked or looked down upon genres of word- and soundplay, and I’m comfortable with it, though I still delight in his calling my own work, many years ago in a private conversation, “patascholarly” (as in the Beatles’ “Joan was quizzical /Waxing pataphysical”). The making of my Boethius translations was not so much a process as an attitude―improvisational, you might even say jazzy.

To this I should add, these collaged translations of mine were the closest I’ve ever come to using words as abstract sounds while still retaining their meaning, which was part of my “pata” intentions. If I were ever to do this book all over again, the resulting translations would be far different.

DELIBOVI

Your work helped clarify for me the voice of the poems. A few are voiced by Boethius, but most are voiced by the character, Philosophy. What are the differences in voice between the two? How does Philosophy change her tone in response to the philosophical concepts she summarizes and punctuates with poetry?

GLASSGOLD

The character Philosophy is serious, empathetic, instructional, and wise throughout, her voice (at least to me) essentially unchanging; severe if need be, likewise comforting―both godlike and parental. Boethius, on the other hand, is emotional and realistically human.

These voices hold for both “her” poems and “his”, but it is “his” that rise from despair to transcendence, that is, in the acceptance of one’s inevitable fate, what in our time is often called “universal awe.” Boethius, in point of fact, is the author of all of the poems, which means he is contending with himself―the hardest of arguments. This is what has made On the Consolation of Philosophy so relatable, both now and in past times. Alfred the Great and Elizabeth I both knew the uneasiness, often deadly, that goes with power. Chaucer, as a minister of state, as well. For such as them, the Consolation was far more than a literary text―it spoke to their condition and their hearts.

I believe it is the deep humanity of the Consolation that made it, of all ancient classics, the most translated into English; far more than Homer and the Bible.

DELIBOVI

What amazes me about Boethius’s poetry, which your translation really brought out, is his use of imagery. For example, in poem VIII of Book III, multiple images express how people, who would never foolishly seek “gold in a green tree,” look in foolish places for their own good. What craft or rhetorical techniques did Boethius employ in image-making? How did capturing this imagery drive you as a translator? What were the challenges of rendering the poet’s images into an older English idiom?

GLASSGOLD

I have no idea where Boethius’ imagery came from―no doubt all airy nothings until set by him to fit the context and his chosen meter. Years ago, the editor for a novel of mine asked me much the same question, “Where does it all come from?” Who knows? An idea comes to you, you think it through for a while, you try it out, and then perhaps it seizes you, and you say to yourself, “Yes, I can do this!”, and so you do. Then as now, I have no answer beyond hard work, training, and experience.

A real difficulty―and part of the pleasure of doing this book―let’s not forget that!―was when the word I was searching, for its sound, rhythm, and meaning in the level of English I felt was needed, couldn’t be found or in fact didn’t exist, perhaps because its very concept wasn’t yet there. In which case, as I recall, I’d have to search for it elsewhere.

Let’s say I wanted a word in Middle English and it proved elusive. I expect I’d looked for it next in early Modern English (say Elizabethan or Jacobean), where there are often some evident linguistic echoes from the recent past. Alas, I have no examples to give you now. Please recall that these collage translations of mine were written years ago, 1988 to 1992, and the earlier edition of the book published two years afterward. I truly doubt that any writer, or any artist of any kind, thinking that far back can remember why they chose this precise word or that, one musical note instead of another, this shade of color or that.

DELIBOVI

Do you have a favorite poem from your book you would be able to share, in part or in entirety, with Cable Street readers? Why is this poem important to you?

GLASSGOLD

The poem I’d like to share is the very first one in On the Consolation of Philosophy. It is a cry from the depths of despair, by a man who had fallen from the heights of happiness and success to absolute rock bottom. This is the poem that drew me into his book and pointed the way to my translations. Except for the a+e ligature(æ)―pronounced in Old English as the “a” in “at”―I won’t be using here some now archaic letters of the early English alphabet, though I do in my book. Also, the present poem opens in my translation with the word “Hwæt”―which from Old English is usually translated as “Lo!” or “Behold!”, to introduce a poem of special, and heroic, significance; Beowulf, for example. There is nothing like it in Latin. I chose to use it because it felt right to me, my only such “poetic” indulgence. All the rest of the words in my collage translations are strictly Boethian. I should add that my book includes a full glossary.

j

Hwæt, ich hwilum yedyde songez in florysching studie,

sorgleoth la! I wepyng am cumpeld to begin.

Me the muses rent dictate I must write,

and elegies with verray teers my face bedew.

No terror at the leest tho muses mihte ofercuman

that they ne beon fellow travelers following my way.

The one-time glory of happy griny youthe

now relieves the fate of me olde man sorgfull.

For elde is comen unlookt for hied by harmes

and sar hath hoten his age to add withal.

Hoore herys untimely ar powrd upon my hed

and from a weakened corse the loose skin quivers.

Happy the death of men that in switest years intrudes

Not but cometh in sorwynges often called.

Eala! with how deef an eere sche fro wrecches wries

and cruel refraines from closing weeping eyes,

While Fortune untriewu favored me with vading goodz

death’s sad hour hadde almost dreynt myne heued.

Now since Fortune cloudy hath chaunged her fickle face,

Pitiless life drags on unkindely its delays.

Why me so oft, my friendz! did you boaste a happie man?

Se feoll, næs his stæpe næfre fæst.

Click here for a review of

Boethius: The Poems From On the Consolation of Philosophy, Translated Out of the Original Latin into Diverse Historical Englishings, Diligently Collaged by Peter Glassgold

* * *