On Francis Carco’s From Montmartre to the Latin Quarter

Francis Carco’s Complexity:

An Afterword by Christopher Sawyer-Lauçanno

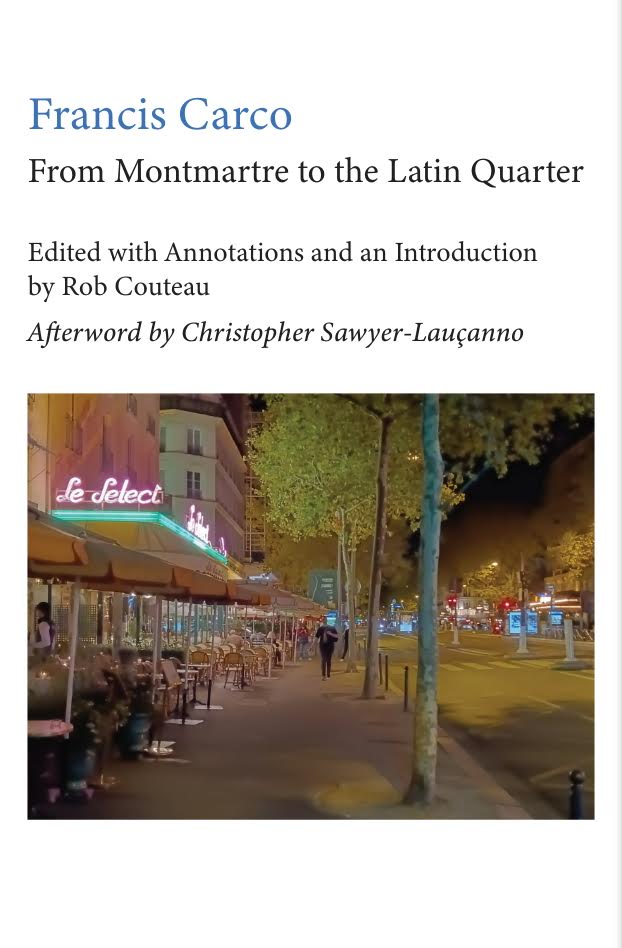

When Rob Couteau asked me whether I would consider writing an Afterword to his new and revised edition of Francis Carco’s From Montmartre to the Latin Quarter, I had to tell him that I had little familiarity with Carco’s work. I had only read a handful of poems and forty years ago his 1925 noir novel Perversité. But then Rob sent me a PDF of his extensively annotated and scrupulously researched English-language edition, and I was hooked. Couteau, again, as he did with Charles Beadle, has made available for discerning readers another much-too-neglected book of great distinction.

Francis Carco is hardly a household name, even among the literati, but he should be. Carco, as Couteau admirably demonstrates in reissuing From Montmartre to the Latin Quarter, has written one of the great memoirs of poets and painters in Paris from before the Great War until the early 1920s.

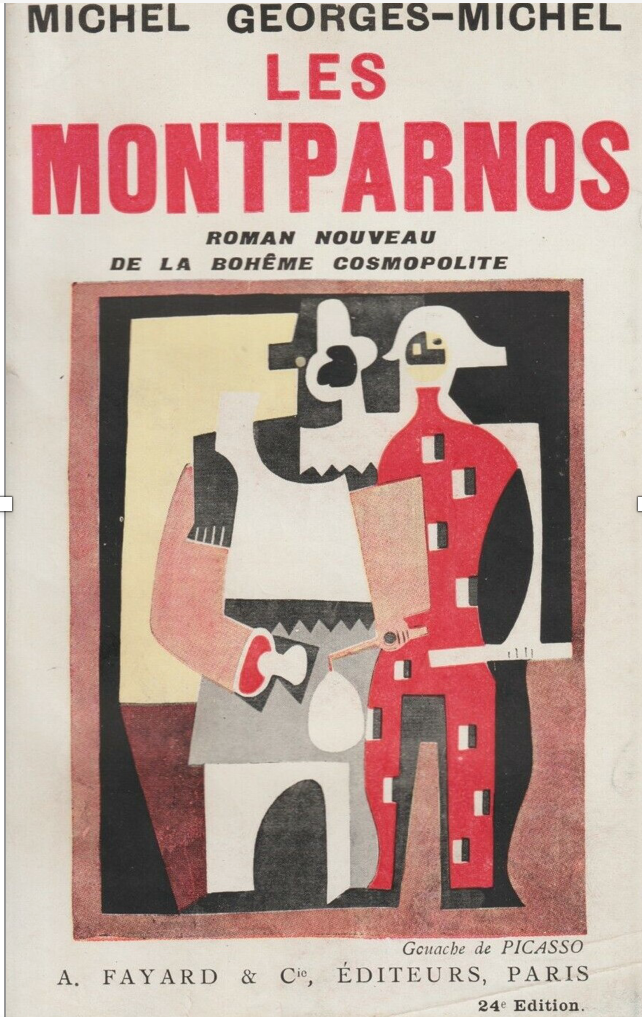

Indeed, I was stunned by the tenderness and even humor Carco exhibits in recapturing the vicissitudes and triumphs of his friends from that period, including, among many others, Utrillo, Picasso, Jacob and Modigliani. I expected vividness but also, given what I knew about and had read before of Carco, a fair amount of raunchiness and even cruelty. Which is not to say that Carco sugarcoats the realities he describes. In fact, he unflinchingly depicts the poverty afflicting these formidable creators, and the squalor in which these artists were forced to reside. He does not dwell on these details, but rather on the kindnesses, the generosity and belief each of his friends exhibited in the face of very precarious circumstances. True empathy and acute sensitivity pervade the book. Aside from Robert Graves’ Good-bye to All That, I can think of no other memoir that brought tears to my eyes. But Carco’s description of the death of Modigliani had me weeping. And then, moments later, I was reveling in the last lines of the book, which focus on Modi’s funeral procession:

People talked about the work he left behind and following the procession, I saw in the ranks the friends of the unlucky Modi. They had all succeeded since the old days. They had all grown older and fatter. Some of them were celebrated, others were going to be: Picasso, Salmon, Max Jacob, Blaise Cendrars … All were there. They denied nothing in the past. On the contrary. With Modi they were burying their youth, and the policemen who, on the way, clicked heels and saluted, perhaps were the same who, so many times, had taken Modi to the police station and who now certainly had no idea that their salute appeared in our eyes a rather belated but public reparation.

It was Picasso, who, as always, drew from that spectacle the lesson it had for all of us, because, turning to me, and pointing first to the hearse where Modigliani rested under mountains of flowers, and then to the policemen at attention, he said softly:

“You see, he gets his revenge!”

Let me explain why From Montmartre to the Latin Quarter surprised me so much. Carco’s reputation is largely built on his sinister novels excavating, with intense realism, the Parisian underworld, or milieu, populated by pimps, queers, prostitutes, gangsters and thieves. In these works, two aspects of his writing stand out for me, make him different from most early noir writers: first, his ability to examine in detail the psychology of his damaged characters, revealing their

inner selves and their deep, often conflicting emotions; second, his use of argot which adds a vivid dimensionality to his descriptions and dialogue.

His early novel Jésus la Caille (1914), which I recently read, is an intense portrayal of a milieu that predates Genet by decades. This richly-layered novel features Jésus, a male sex worker, who is also enthralled with Fernande, a prostitute whose wretched life is ensnared between her sadistic pimp and a seriously troubled police informant. Violence is continually present, or just around the corner, so that the entire novel is infused with an air of constant malevolence and apprehension. Carco demonstrates an amazing ability to get inside the heads of each of his characters, and to his credit is never apologetic about who they are. They simply exist, just as the denizens of the impoverished streets and squalid bars Carco knew well, existed. He has no interest in assuaging any moral expectations on the part of his readers.While seemingly detached from moral observation, one can’t help but feel, as Couteau explains so well in his Introduction, that Carco also takes a certain delight in obsessively observing the misery of his characters. In Perversité, for instance, the sordid lives of his characters and perversity of plot are told with so much detail that it appears Carco relishes writing about the destruction of his creations. In Perversité Emile, a self-effacing office clerk, and Irma, his prostitute sister, with whom Emile is secretly in love, share a cramped apartment in a tenement house populated by prostitutes. Emile largely manages to ignore how his sister makes her living, until she takes up with Bébert, a violent pimp, who quickly uncovers Emile’s timidity. Delighting at the discovery of Emile’s weakness, Bébert proceeds to bully him (and Irma) relentlessly. Emile, in turn, takes up with Belle-Amour, an older prostitute neighbor, on which he reenacts the treatment Bébert has been inflicting on him and Irma. The ultimate tragedy of the novel is that Emile purchases a gun to kill Bébert but ends up killing his beloved Irma instead.

Carco writes so vividly and so unrelievedly about the abuse, that I found I had to stop reading from time to time to recover from the ardent misanthropy on display. Or to be blunt: I found myself squirming a lot.

In 1915 Carco had a brief affair with Katherine Mansfield, who wrote two stories about him. Her 1915 story “An Indiscreet Journey,” based on an actual four-day visit Mansfield made to see Carco who was at the front during the war, does not probe deeply into “the little corporal” (Carco). Indeed, the focus is as much on the other soldiers in the café as it is on the relationship.

But between 1915 and 1918, Mansfield decided to examine Carco’s dark side which she reveals without reservation in her 1918 conte à clef “Je Ne Parle Pas Français.” Sadism, masochism, homosexuality, cuckoldry, prostitution, pimping: Carco’s themes. But also, his actual obsessions as well, if we are reading Mansfield correctly. The narrator, Raoul Duquette, a Parisian writer and pimp based on Carco, recounts bits and pieces of his life while ostensibly telling a tale of Mouse (Mansfield) and Dick Harmon (John Middleton Murry, Mansfield’s husband) within the context of carefully describing himself. Mansfield’s brilliance is the way she reveals so much about each of her characters through their own words and actions. At the beginning of the story, in Paris, Duquette and Dick form a tight “friendship” based on their love of literature. When Dick announces he must return to England, Duquette is both furious and hurt. It’s evident that his attraction to Dick is hardly brotherly. But then when Dick brings his lover Mouse back to Paris, Duquette’s true character begins to emerge. His voyeur instinct comes full forward, as does his derisory view of those he watches. He compares himself to a customs officer who thrills at examining those inspected to force them to reveal what it is they have to declare.

As the narrative progresses, the contrast between the preying Duquette and his far more innocent victims, Dick and Mouse, becomes more evident, as does Duquette’s delight in the destruction of their relationship. It is a story worthy of Carco; in “Je Ne Parle Pas Français,” however, it is Carco who is mercilessly dissected.

That Carco was complex as a writer and human is indisputable. That he could write such a sensitive book as From Montmartre to the Latin Quarter as well as author his gruesome noir novels is decidedly contradictory. My sense is that the side of Carco who wrote poetry – lyrical, post symbolist, evocative of nature and weather – the “poète de la pluie,” as he was dubbed by his contemporaries, is the writer behind the memoir. His sensitive attention to detail in his poetry is mirrored in the souvenirs of his friends, their creations and their times; his tremendous love for art and artists, on display in his homages to Villon, Verlaine, and Rimbaud in his poetry, is what guides his empathetic observations in From Montmartre to the Latin Quarter.

Jean Rhys, an acute observer of human nature who translated Perversité into English, and who spent a fair amount of time in Carco’s Paris, wrote from the point of view of an unnamed narrator in her 1927 story “The Blue Bird” this observation which seems to sum up a good deal of Carco’s dual vision: “Montparnasse is full of tragedy – all sorts – blatant, hidden, silent, voluble, slow – even lucrative – A tragedy can be lucrative, I assure you. On any day of the week you may catch sight of the Sufferers, white-faced and tragic of eye – having a drink in the intervals of expressing themselves – pouring out their souls and exposing them hopefully for sale, that is to say.”

In the end, we are glad for both Carcos. He was truly a literary giant. All praise to Rob Couteau for helping contemporary readers in English rediscover this important figure. Due to Couteau’s copious and detailed and revelatory research, an entire panorama into the world of art in Paris – particularly that of Modigliani’s circle – is opened to us. Replete with new and fascinating discoveries about both Carco and Modigliani, this edition immensely advances our knowledge of art and artists, collecting and trading during an important period in European art history. To his credit, Couteau even manages to identify for the first time what exactly were the Modigliani pieces in Carco’s possession, and even the prices they fetched at auction. These are valuable details, the result of Couteau’s willingness to keep digging into the archives, and then digging more. A rich portrait emerges that expands exponentially on Carco’s already detailed memoir.

This is a gift for which I am admiring and grateful.

***