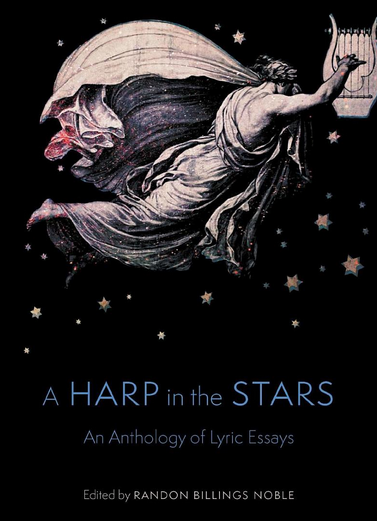

A Harp in the Stars: An Anthology of Lyric Essays

edited by Randon Billings Noble

When is an essay not an essay? When it is a lyric essay, a genre currently inspiring some of the best new prose around. The lyric essay forgoes the conventions of essay-writing for images, structures, and progressions akin to those in poetry and fiction. Like the liar’s paradox, where the words “I am lying” are only true if they are false, the paradox of the lyric essay is that it’s only a lyric essay if it’s not, in the conventional sense, an essay at all.

Because the lyric essay is both paradoxical and popular, it cries out for a thorough exploration. Randon Billings Noble has done the job brilliantly in her anthology, A Harp in the Stars. The book is a cornucopia of 50 lyric essays; included are several pieces and a series of meditations on the craft of the genre. A Harp in the Stars both exemplifies and teaches the lyric essay. It belongs with other important craft books for writers of creative nonfiction, such as Brenda Miller’s Tell It Slant and Phillip Lopate’s To Show and to Tell.

I will say up front that I remain hopelessly traditional in my essay construction. I can’t seem to shake the memory of Mrs. Hewitt’s 10th grade English class or my philosophy training. I am not sure I could ever write a lyric essay. But after reading A Harp in the Stars, I want to try. In other words, Billings Noble’s anthology opened my closed mind, which is the ultimate testament to its value.

Billings Noble introduces the anthology with a helpful definition and an even more helpful typology of the lyric essay. The lyric essay’s “wily capriciousness” resists a single definition. It has to be defined by a menu of options:

…a piece of writing with a visible/stand-out/unusual structure that explores/forecasts/gestures to an idea in an unexpected way.

Lyric essays fall into one of four broad types, deftly presented by Billings Noble. Flash essays are short, brisk essays of 1000 words or less (there are two fine examples of flash essays by Ian C. Smith in this issue of Cable Street). Segmented essays are essays divided into sections by various devices—numbers, titles, or white space—and tend to have connections but not continuity among sections. When a segmented essay has a pattern of repetitions, it is called a braided essay. Finally, the hermit crab essay takes another form for its “shell” or structure, such as a menu, a to-do list, an instruction sheet, a legal document, or any other structure a writer chooses to borrow.

Identifying the lyric essay as a genre may be new, but the creatively structured essay is not. The poet Mary Ruefle has experimented with lyric essays since the 1990s. Long before, 10th-century writer Sei Shōnagon wrote in her Pillow Book what might be called flash essays (see Naoko Fujimoto’s homage to Shōnagon in this issue). Centuries-old forms like haibun (anthologized in this issue), the numbered treatise, and the autobiographical and virtues catalogs of the ancient world all have qualities at home in the modern lyric essay. As Billings Noble writes:

When Sei Shōnagon was noting observations in her pillow book, she wasn’t thinking about whether her lists and notes would be considered essays, lyric or otherwise. But by the 1990s, a thousand years after she has written them, excerpts were anthologized in Phillip Lopate’s The Art of the Personal Essay, and they became, indeed, essays—lyric essays.

After telling us about the lyric essay, Billings Noble shows us. She has carefully curated the lyric essays in this anthology to exemplify the four essay types. Every essay makes a valuable contribution to the whole. There are also some real standouts by Diane Seuss, Layla Benitez-James, Kristina Gaddy, Christen Noel Kauffman, Steve Edwards, Lia Purpura, and Billings Noble herself.

One of my favorite essays in the collection, the braided essay “Woven” by Lidia Yuknavitch, demonstrates the power of the lyric essay to infuse nonfiction with emotion. With astounding dexterity, Yuknavitch braids a story from her young adult life in Greenwich Village with Lithuanian myths told by her grandmother and experiences in a marriage. The essay is full of twists and heartbreak; each paragraph of prose is like a prose poem, sonorous and image-rich, as in this paragraph retelling the Lithuanian myth of the water spirit Laume:

Laume came from transcendental waters, and her spirit lives in all waters, even in baths and showers, in rivers, streams, oceans, the rain, and in toilets. She is the guardian of all children, the not yet born, the newly born, the orphaned, the forgotten, even the dead. If there is a child coming into the world, she can foresee it. If a child is mistreated, she will sometimes take him and raise him herself. If a child is lost, she protects him while gathering information about the usefulness of the parents. If parents are mishandling a child, she will transform him into whatever lesson they needed to learn.

Another inspiring essay in the anthology is Nels P. Highberg’s “This Is the Room Where.” In this flash essay, the text completes the title, a technique of contemporary poetry; the entire essay is a single sentence divided with semicolons until its unexpected conclusion. The form of the essay works with the content, to deliver a piece that reminds us that the spaces of our everyday life are rich with meaning.

The final section of A Harp in the Stars—”Craft Essays”—uses lyric essays to instruct and motivate writers who want to work in the genre. Every essay in this section is a worthy addition to the whole. Another section, “Meditations” provides short statements on the craft of the lyric essay by authors included in the anthology. My only unfulfilled wish in this section would be a hermit crab essay, taking the shell of a recipe or manual, with numbered steps on writing the lyric essay.

Among the craft essays, Heidi Czerweic’s “Success in Circuit: The Lyric Essay as Labyrinth,” has proved particularly helpful to me. This essay emphasizes how a lyric essay turns and turns—leading the reader in, then guiding her out—with perhaps an Ariadne-thread of meaning dropped along the way.

Another craft essay has proved particularly unsettling: Chelsey Clammer’s “Lying in the Lyric.” Knitted into Clammer’s text is the suggestion that the lyric essay may be the ideal genre to show the progression from exaggeration and self-censorship—that is, lying—to confession of the lies. “Lying in the Lyric” has basically called me out on the lies in my essays, which the conventional essay form, with its linear flow, allows me to keep in place. In contrast, the weaving and patterning of the lyric essay permits revisiting text, gradually admitting the lies and squeezing out the truth.

This process of confession is common to every lyric essay in A Harp in the Stars. Beneath it, is the ultimate paradox: since every essay lies, the only solution is an essay that’s not, conventionally, an essay. Randon Billings Noble has created an anthology that points us toward more truthful nonfiction; her collection is a service to writers and readers that merits a place on everyone’s bookshelf.

—Dana Delibovi

***