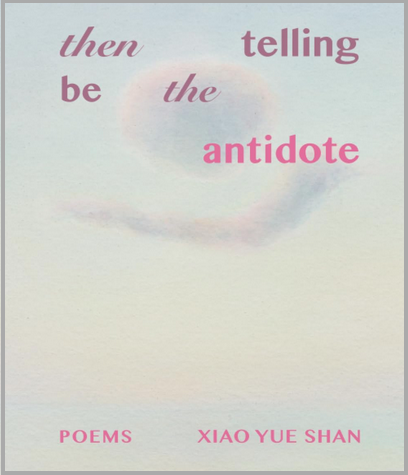

then telling be the antidote

Poems by Xiao Yue Shan

Our lives pass with so many words left unspoken. Not secrets, but moments and thoughts that we keep to ourselves. These sequestered fragments shape us, and poets can shape them into images that carry great emotional weight. The poet Xiao Yue Shan is a master of this skill. She resurfaces what we hide and articulates what we silence through her Berkshire Prize-winning poetry collection, then telling be the antidote. With impeccable control over language and a deep sense of understanding of the world, Shan reveals images of history, family, growth, and desire in finely wrought poems. Telling is her antidote to suppression.

Craft is the starting point for an analysis of Shan’s poetry, because her stylistic choices are essential to both her voice and her project of exposing what is obscure. Shan excludes nearly all capitalization and plays with syntax across the lines, techniques that add intimacy to the writing. Foregoing capitalization has a softening effect on the text; the poems retain a powerful resonance, but the words feel down to earth and graceful. Lack of capitalization combined with syntactic inventiveness also help Shan blend lines and figures together, while still maintaining the clarity of individual phrases. Lines do not end when the idea ends; they end when Shan decides they must, to release the emotion concealed in the image.

The poem “in love as in tourism” is a prime example of Shan’s craft. The poem narrates how liberating the act of travel is. This section of the poem is a rush of phrases that are all unique images, yet develop into an overarching motif:

cartography seems the strangest science today

as morning alters the fittings of the hour to form

shapes wholly new. wishing I did not know that, to leave,

it is down and right past the neighbour’s potted palm,

across the street to meet the river, then ahead until

the train station crowds into view—I search the infinity

enclosed here, for any time that the future could spare.

This passage shows also shows another aspect of Shan’s syntax—its ability to deepen meaning. The words “wishing I did not know that” can be read from the perspective of the previous line, where Shan wishes that mapping her world wasn’t so confusing, or from the following line, in which case Shan wishes to not know how to depart from the environment where she dwells. Shan’s syntax builds complex and insightful layers into each poem.

Shan’s craft complements the layered themes of her poetry. One example of this is the recurrence of the natural world in her work. Fruits and flowers, trees and rivers shape Shan’s writing, making it feel primordial and earthy. However, Shan recognizes the dichotomy between nature and our constructed world of plastic and metal.

The shift between the natural and material world is demonstrated in the poem “wealth distribution will not be considered in the economic reform.” Here, Shan describes the characteristics of poverty in China. By switching between objects from the earth and those made by man, Shan exposes the covert connections between the themes:

…shanghai was a firearm of a city,

grease-dark mechanics and a heavy

presence in the drawer of the day. fruit skins

draping the curb, estranged gauze of huangpu

river. pillowcases filled with plastic wrapping.

the trigger twitches—this close to a bicycle

for your wife. this close to a couple months

of rent. this close to cottoning the quilts

for a winter and tangerines every summer night.

Opposing themes like this are a constant within Shan’s work. Growth and aging are seen through the lens of history, the liberty of a bird tangled in the fortitude of a mountain. The duality of opposing ideas repeatedly surfaces in Shan’s poetry. It feeds into the power to identify juxtaposing thoughts, which, left unspoken, can cause a lot of mental fatigue. By bringing these opposites to light, even if the dilemma they pose can’t be solved, we obtain rest and clarity.

Shan’s cultural background is another theme reflected throughout her writing. Shah was born in Dongying, China, and her culture of origin has a deep influence in her poetry. Many of her poems are based on Chinese history, or deal with modern societal issues in contemporary China. There are many other ways Shan’s background bolsters her writing, such as splicing Chinese words into English poetry, or using metaphors and symbols dominant in Chinese culture. The poem “the emperor and I dream of immortality” is one of the many examples of writing influenced by Chinese culture. In it, Shan considers the implications of immortality, either literally, like the first Chinese emperor Qin Shi Huang, or symbolically in offspring or legacy. Topics of womanhood and childbirth also seep into the poem—once more, Shan uncovers the layers of hidden meaning:

in twenty years I will be forty nine years old

the age of the qin emperor when he died

bribed from life by a mercury pill

clutching china in spinning palms

and a hundred rivers were embedded in his tomb

alongside massacred soft heaps of women

by which the emperor insured his rest

All these traits of Shan’s writing trace a web around the theme of desire. A desire that manifests itself in a multitude of different ways; to be loved, to live a long life, to travel but to find her home. Shan’s series of poems, titled “montreal” I-V, describes Shan’s feelings of isolation and not fitting in when she lived away from home in an English-speaking country. “montreal II” has a powerful excerpt about the desire to live somewhere one feels belonging and comfort:

I was getting lost all the time so I had to pick up smoking. I mean with

a cigarette you could stand on the side of the street and lean up against

the black haunt of wrought iron or the paintingly green staircases of

august foliage or the parking meter and you could wait. you could let

the world demonstrate its order to you, all the while looking as though

you belonged in it, in the era of perfect maps and imperfect memory.

Although most of the layout choices in the book contribute greatly to the intimacy of the poetry, formatting on the page can leave a bit to be desired. Sometimes, it is difficult to visualize where poems start and end, due to all the text appearing in lower case. For instance, it can be disorienting when a poem bleeds on to the next page, as one may think the poem ends earlier than it is supposed to. One organizational solution for future editions could be to start any poems two or more pages long on a left page, so it is easier to identify the continuity.

Overall, then telling be the antidote is a masterful work by a poet clear in voice and concept. Xiao Yue Shan combines a unique style, cultural insight, and wide perspective to examine her desires, past, and future. Her poetry feels timeless, yet still relevant to contemporary living. Shan frees the hidden truths inside her with force yet gentleness. She won’t be silenced—and we are better for it.

—Joseph Hess

***