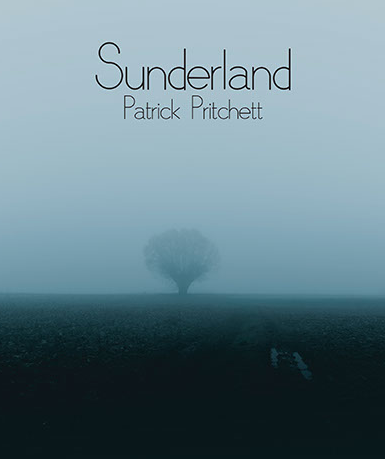

Sunderland

By Patrick Pritchett

Patrick Pritchett has been writing very good poems for a very long time. Sunderland, his latest, soars beyond everything he has written before. This sequence of poems, linked by the omnipresence of Covid, disillusion and rupture of the ordinary, pushes his readers into places ripped apart, sundered, so to speak: “The sky is always a ghost now /set to residential zero.” It’s been an honor to publish some of this sequence here in Cable Street.

What we have in Sunderland is erudition meeting the acute observation of terrible beauty. The result is reflection on how we came to be “between the earth / as seen and the earth about to vanish” and whether there is any outlet for “a disturbance in a field of disturbance.” Pritchett knows and reminds us throughout the book that there are no easy answers. He does attempt some decipherment of our state of being by searching for understanding through the evocation of a myriad of preceding voices who struggled with the same dilemma: Trakl, Rimbaud, hungry ghosts, religious writers from the Mesopotamians, Egyptians, Persians and Greeks to the Biblical prophets and commentators. And yet, none of these provide him with solace, just more entanglement in “What is empty./What is returning.”

Full disclosure here: I have known Pritchett as a fellow writer for more than a decade, have been reading and admiring both his remarkable poetry and important criticism even longer. That said, I do not believe my association has influenced my objectivity; our mutual focus has always been on poetry and poetics, not on our day-to-day comings and goings.

Lots of writers chronicle their personal despair or concerns for the state of our world. Most end up wallowing. Pritchett never does, partly because he is so aware of the importance of how language is the vehicle that encompasses all we say and how we say it. Like most poetry, his poems simultaneously exist on two planes: that of denotation and connotation. But Pritchett wraps language around itself so that the denotations themselves become connotations, and these connotations are multiple, evocative, at times almost unknowable. What seems like a simple observation suddenly morphs into a universe bursting above our heads.

“At Sunset,” for example, begins with a rather mysterious couplet that could be seen as denotative, then suddenly, the poem veers into unexpected visualizations not readily seen by the eye. Each couplet creates a definitive pattern dependent and yet independent of the one that preceded it. The result is an omnidirectional vigilance in which clues confuse and yet expound on the topic of endings that have no endings, located somehow within the poet being the hero of his own demise.

At Sunset

And once again I am

the hero of my own demise

in a story about endings

that has no end

a story about ghosts

and the light at the edge of things

and how the atomic flicker

that wears down all matter

wears down the horizon, too

until all that is left is a thin smear.

I am counting the minutes

which live out their afterlives

in the feral void of flashes

& spasms, inky gnostic flares.

And I am laving my cold hands

in the white glow of this snow

till they erase the one

promise they made good on.

New language, at least to us, propels the couplets while the couplets propel the language. What is denoted and connoted defies expectation since the linguistic intricacy sets up competing fields of meaning. The poem begins in the concrete and returns to the concrete in the penultimate stanza, only to focus again in the closure on something unseeable. Along the way impossible juxtapositions push our senses to expand, if not wholly understand.

I could have chosen any poem from Sunderland since Pritchett consistently explains and baffles at the same time, uses his line and stanza breaks to enrich possibilities of what comes next. What we quickly come to realize is that Pritchett has invented his own sets of linguistic rules. We could, of course, attempt to decode the schemes but it seems more fruitful to recognize that hidden systems exist, and explore their discursive potentialities. Or as Pritchett describes this in “Translations:” “The tenuous / membrane tending to / the casualties of logos.”

Pritchett, himself, does just that in the section of his book entitled “Trakl in Sunderland.” Indeed, in the nine poems in this section, he evokes the language and techniques of his early 20th Century Austrian counterpart and their mutual concern with the world inexorably collapsing around them. Like Trakl, he uses freely-associated, or sundered imagery, that conveys despair, abandonment and an inability to commandeer a realistic sense of hopefulness in what is experienced. Here’s the opening to “The World:”

Trakl says it’s

as if the world

were already so

written over

as if enough has

already happened

to put a close

to the poem.

As if “happened”

were not a word

replacing “stab”

or “disappeared”

or “gone forever”

except that little

songs still survive

they dig in under

they go sub-

cutaneous

they go on

no tomorrow.

What Pritchett has done here is rework the poet’s cadences, tone, unexpected linguistic leaps and sense of dire dread into his own engaged expression. Trakl serves him not as a muse or even model but as a fellow seer who envisions the same world in which destruction and helplessness situate themselves in “little songs.” But just as the Austrian poet could not find his way, even through prayer, neither can Pritchett. It makes the poems in this section even more of a commentary on how the state of things has been and will be, where what is denoted (the world/poem written over) is also connoted by the images of what such a circumstance alternatively evokes: words that should go on end in “no tomorrow.”

Pritchett is also very in tune with Trakl’s eye as he observes the natural world near his former stomping grounds of Sunderland, Massachusetts. Despite its beauty, the landscape is also viewed as sinister. This surfaces in several poems in the collection, not just those specific to Trakl. His “Snow,” for instance reminds me of lines from Trakl’s “Winternacht.”

(From Pritchett’s “Snow”)

Snow destroys the visible.

Therefore, it is beautiful.

To leech light from each perceptible thing.

Bury it in a sarcophagus of white.

(From Trakl’s “Winternacht“)

Schwarzer Frost. Die Erde ist hart, nach Bitterem schmeckt die Luft. Deine Sterne schließen

sich zu bösen Zeichen….

Bitterer Schnee und Mond!

Black frost. The earth is hard, the air tastes of bitterness. Your stars close into evil signs….

Bitter snow and moon!

(Sawyer-Lauçanno translation)

Sunderland, as is obvious, is not an easy book. But it is a highly significant contribution to our poetry and our time. It also fully proves that Pritchett is a necessary and masterful poet. Or as he writes of Trakl: “[He] enlarges the world / just by speaking.”

—Christopher Sawyer-Lauçanno

***