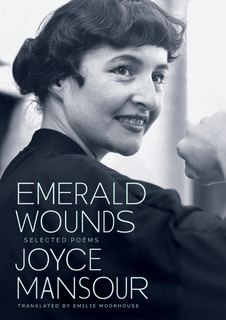

Emerald Wounds by Joyce Mansour

Translated from the French by Emilie Moorhouse

In the spring of 1973 I was briefly a graduate student in Comparative Literature at UC Santa Barbara. Because I was working full-time and helping to raise two young daughters, I could only take one class. I chose Anne Hyde Greet’s “Le Livre de Peintre en France.” A noted scholar on Apollinaire and the Surrealists, Professor Greet led her handful of students through a marvelous variety of collaborations between poets and painters in France. I fell in love with the interplay between words and images, and read well beyond the required texts. I had already become an enthusiast of Surrealism and so sought out Professor Greet for advice. We ended up meeting weekly to discuss Breton, Aragon, Soupault, Eluard and many others. One day she loaned me a book by a writer totally unknown to me: Joyce Mansour. She said something to the effect that this book would really open my eyes.

Professor Greet, of course, was right. I was immediately overwhelmed by Mansour’s language, raw intensity, and the focus on self in all its complexities. This novel absorption in all aspects of who the actual female being really was, radically reversed the male posture of the idealized woman.

By the time I read Mansour, I was quite well versed in the love poems of Desnos, Eluard and Breton. What struck me was how her diction was decidedly Surrealist, but her expression was unique. While Breton, at the conclusion of Nadja announces that “beauty must be convulsive or it will not be,” Mansour demonstrates, largely unlike Breton, how this is fully realized. And Emilie Moorhouse, in her felicitous translation of selections from Mansour’s vast oeuvre entitled Emerald Wounds, just published in a bilingual edition by City Lights, allows anglophone readers to see how “convulsive beauty” actually gets written. In her very informative introduction, Moorhouse tell us that Mansour (1928–1986) was born Joyce Patricia Adès in England. Her family was of Jewish-Syrian descent. At a young age, her family moved to Cairo. The language spoken in the house was English. When she was 15, her mother died of cancer. Mansour was inconsolable. In a poem she wrote some years later, she described her emotions:

There are no deeds

Only my skin

And the ants that crawl between my unctuous legs

Carry masks of silence while laboring.

Come night and your bliss

And my deep body, mindless octopus

Swallows your excited cock

As it is born.

Such frankness is new and fresh, and while the depiction is decidedly Surrealist with startling and unexpected imagery, and focuses on the woman as an object of desire, she departs from the men in not idealizing the woman but presenting the woman as a breathing, desirable and desired flesh and blood being.

This concentration on the female self as an actual person continues throughout her work. In doing so she upends the traditional Surrealist male position of the woman-mirror image. In the love poems of Desnos, Eluard and Breton, in particular, the mirrored female allows the male poet to envision a woman as part of himself. In doing so, of course, he denies the woman her own being.

In the conclusion of a poem from her 1965 collection “A Myriad of More Deaths” (Des Myriads d’Autres Morts) which contains the line “so many emerald wounds,” that gave Moorhouse her title, Mansour writes:

I no longer wait for vulgar affection

I cross moons deserts lakes

I am the animal of the night

Madness says the man

To dream like this

You will lose your diamond

The corridors of space

In other words: I am my own physical being, not some illusory embodiment of your fantasies.She takes a somewhat more subtle, yet no less powerful approach in the concluding lines of “Sun in Capricorn” (Le Soleil dans le Capricorne):

I no longer wait for vulgar affection

I cross moons deserts lakes

I am the animal of the night

Madness says the man

To dream like this

You will lose your diamond

The corridors of space

Still smiling your hand thunders indifference

Dressed cruelly tilted towards emptiness

You say no and the smallest object housed in a woman’s body

Arches the spine

Artificial Nice

False perfume from the hour on the couch

For what pale giraffes

Have I abandoned Byzantium

Loneliness sucks

A moonstone in an oval frame

Yet another insomnia with rigid joints

Yet another dagger pulsing under the rain

Diamonds and deliriums of tomorrow’s memories

Taffeta sweat homeless beaches

Madness of my flesh gone astray

And more explicitly she states the prominence of her own self in mocking tones in these lines from “In the “Dark to the Left” (Dans L’Obscurité a Gauche):

Why would I wait in front of a closed door

Shy and pleading steamy cello

Have children

Drench your gums in rare vinegar

The most tender white is tinted with black

Your dick is softer

Than the face of a virgin

More irritating than pity

Scribbling tool of this incredible hurly-burly

Good-bye so long it’s finished Adieu

These are poems in which the woman is fully accepting of the consequences for going her own way. The emphasis is on woman being able to direct her own desires, her own life. These were hardly assertions commonly heard from women in the 1950s and 60s. Indeed, throughout Mansour’s work this is more than an occasional theme. It is a statement of fact relayed over and over again, even in poems with less overt pronouncements. In Moorhouse’s selections, we see this come through with clarity.

Moorhouse is a faithful translator. Even though she omits poems from several collections, most notably (for me) from Phallus et momies and Le Grand jamais, credit is due for her inclusion of the complete later books Pandémonium (1976), Jasmin d’hiver (1982), and Trous noirs (1986). Of the poems she chooses, she ports over into English Mansour’s intensity and her often idiosyncratic language. I wish, though, that she had also attempted to recreate some of the noticeable assonance and metrical rhythm inherent in the poems. She did, however, wisely decide not to force Mansour’s occasional rhymes or slant rhymes into a stilted English but allows the poems to flow, as they do in French. I don’t always agree with the particular words she selects as equivalents for the French but with one exception, they are not wrong, just different from what I would have chosen. The one mistranslation I uncovered was in “Advice from a Sister” (Conseils d’une Conseur) where she mistakenly translates “pile” as pile when Mansour actually employs the argot word for an electric battery:

Achetez / la pile Albert, elle ne s’allume qu’une seule fois et tue quand on s’en sert.

Buy the / Albert pile, it only turns on once and kills when it’s used.

A tiny error and easy to make.

This is a very welcome translation, one English readers can trust. Mansour should be far more read (in both French and English) than she is. Emilie Moorhouse has performed an invaluable service to her and to French literature in English. For a fascinating interview of Morehouse on Mansour, with thanks to Dana Delibovi who ferreted out this interview, see,

— Christopher Sawyer-Lauçanno