By Christopher Sawyer-Lauçanno

I realized at almost the moment I sat down to write a remembrance of Ned Rorem, that it would not be possible to write about Ned without bringing in Virgil Thomson, Paul Bowles and John Cage. They are all linked for me to Rorem. Indeed, it was Virgil who first introduced me to Ned, in probably the early winter of 1986. At the time I was embarking on writing my biography of Paul Bowles, and in the mid-80s, I spent a fair amount of time in Virgil’s ninth floor, red-walled Chelsea Hotel apartment talking to him about Paul, but also about Paris and Stein and a hundred other subjects. As it so often happened for me, what began as an initial “call of duty,” soon became some sort of friendship.

One afternoon, probably in early 1986, Virgil handed me a slip of monogrammed note pad, on which he’d written two telephone numbers: one for Ned Rorem, the other for John Cage. “You need to talk to them both about Paul,” he said. “Ned will have all the gossip. John will have insights.”

Virgil really was the “father of them all.” In one way or another, Ned, Paul and John (along with scores of others from Lou Harrison to Leonard Bernstein to Henry Cowell) had been nurtured by Virgil, had learned from him. He taught Paul how to write orchestration and helped get him commissions for theater incidental music. Ned was his copyist and understudy; in particular, Ned learned from Virgil the art of setting words to music.

Virgil collaborated in 1945 with Cage (and Cowell and Harrison) on Party Pieces, using a method of composition in which one composer would write a bar of music plus two notes, fold the paper at the bar, and pass it to the next composer, who would use the two notes as a base for continuing the piece. Cage in 1950 also wrote the first book-length study of Virgil’s music. And just as Virgil introduced me to Ned and John, he introduced them to everyone, advancing their careers, bolstering their efforts.

Within a day or so of receiving the phone numbers, I called both Rorem and Cage. I left a message for John. Ned picked up. He told me he had already heard from Virgil and invited me over to his apartment on the upper West Side. He was warm and seemed very interested in imparting tales of Bowles.

I likely met Ned in person a day or so later. I remember it was raining torrentially, with some sleet mixed in. I arrived at his apartment drenched from the short walk from the subway station. In contrast to Virgil’s colorful French-style apartment with its red walls lined with paintings, Ned’s walls, where visible, were starkly white. But as chez Virgil, paintings took over the walls: Larry Rivers, Jane Freilicher, Joe Brainard, Maurice Grosser, Nell Blaine, Leonid and others. Several Cocteau drawings were displayed behind the Steinway. Books and recordings filled in spaces elsewhere.

Ned was very welcoming. Even at 65 he had retained his rather famous (or infamous) very good looks. Within a few minutes of my arrival, he went to the piano and played from memory Bowles’s “The Wind Remains” from his opera Yerma, based on Lorca’s play. I already knew the music but was unprepared for such a rendition: fulsome, resonant, con brio. This opened up a long conversation about Paul as a composer. Ned, like Virgil, was quite taken by Bowles’s music. While he was quick to acknowledge that Virgil had provided him with his initial training in “the words and music thing,” he credited Bowles with furthering his education when he briefly worked for him as a copyist: “Paul was the finest craftsman of art songs that America has produced.” Many have said the same about Ned. I pointed this out. “Paul has always been an inspiration,” he said. “Had he not stopped composing, no one would have surpassed him. Not [Samuel] Barber. Not me. If I have. There’s not really any competition. I just do what I do.”

Ned was not so complimentary about Paul’s acclaimed fiction. While he was quick to acknowledge that “Paul became more famous in one day for writing The Sheltering Sky than he had in all his years writing music,” he lamented that Paul had gone from “the composer who writes words” to “the author who occasionally writes music.” I asked Ned about his own illustrious career as a tell-all diarist. “For many,” I told him, “You are far better known for your writing than for your music.” “That’s not my fault,” he said. “I am a first and last and always a composer who writes words now and then.”

I have to confess that when I first met Ned, I was one of those who was more familiar with his writing than his music. The late poet and librettist Kenward Elmslie (who should have a Viva of his own) did give me the album of Miss Julie, Ned’s spirited opera for which Kenward wrote the libretto. I also had some awareness of his art songs and works for piano, as well as Air Music: Ten Etudes for Orchestra, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 1976. But compared to my knowledge of the music of Virgil or Paul, I was considerably lacking in my acquaintance of Rorem’s compositions. I sought to remedy this by buying some sheet music of his art songs. Ned supplied me with a number of recordings and I picked up more. I soon came to realize that Ned was clearly one of the most distinguished composers of his generation. His art songs were unsurpassed, his orchestral works nuanced and unpredictable. Indeed, Rorem’s compositions are continuously rich, vast and varied, entertaining in the best sense of that word, with a definite French sensibility.

Rorem became enamored of the modernist French composers while a student but was nourished in that direction by Virgil and Bowles. Eight years in France only more firmly cemented his relationship to French music. In particular, Les Six, Auric, Durey, Honegger, Poulenc, Tailleferre and Milhaud were of seminal importance, as was Satie who loomed powerfully over the group, as he did over Thomson, Bowles, Rorem and Cage. Indeed, Cage once remarked to me that Satie bound Paul, Ned, Virgil and him together despite the vast differences in approaches to composition.

While Bowles was the initial reason for my seeking out Rorem, it became evident rather quickly that we enjoyed spending time together. As Francophiles, and with other friends in common, we had lots to talk about. And I always enjoyed Ned’s gossip. We dined together on several occasions, took in a couple of concerts, argued about twelve-tone music. Ned jokingly referred to composers of serial music as “serial killers.” I often couldn’t disagree.

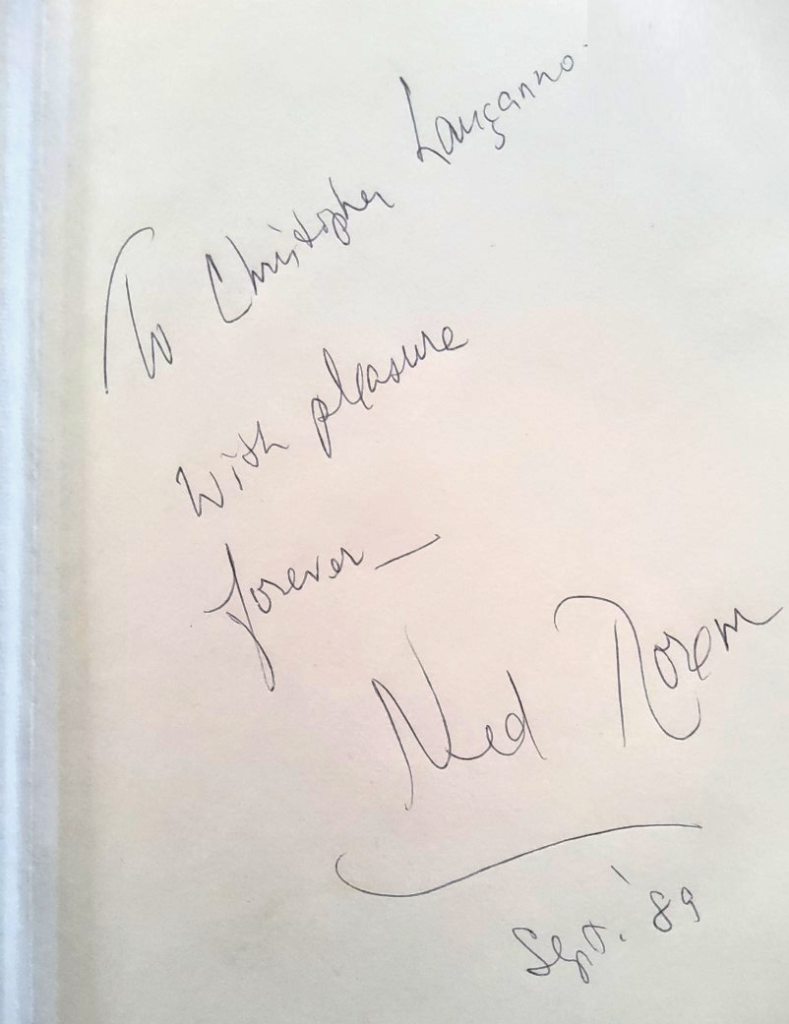

In the fall of 1989, Ned invited me to spend a few days at his 1919 bungalow on Nantucket that he shared with his long-time partner Jim Holmes. The place was right in the middle of town, near a bookstore, a news vendor and cafés. Since they purchased the place in 1974, Jim had done major work on the house, put in gardens, and landscaped the half-acre lot. I remember thoroughly enjoying my time there. Ned was an amazing host, taking me around the village, making sure I met everyone, even arranging a book signing of the Bowles biography at the local bookshop.

After that visit, I only saw Ned a few times but we wrote letters fairly regularly and spoke on the phone from time to time. And then, the word came on November 22, 2022 from a friend: Ned was dead at 99.

After the death of Lou Harrison in 2003, Ned sent me a tribute he had written for him. His words about Lou seem appropriate as a way of closing my Viva:

There is no right time to die. All death is unexpected. The older our friends become, the more we feel they’ll always be there….As for our own death, Freud claimed it is unimaginable, “and when we try to imagine it we perceive that we really survive as spectators…In the unconscious every one of us is convinced of his own immortality.” But for artists, immortality is a given. Thus [we] will continue living, not just in the minds of the brief mortals who knew us, but forever in our recordings and concert halls.