A Welcomed View—

Three Books on Seeing and Being Seen

Every artist, every writer is a host. What is she putting on offer? How welcoming is she? And what happens when a viewer or reader is not the guest the visual artist or writer expected?

Three slim books―Tina M. Campt’s 2017 Listening to Images, Tisa Bryant’s 2007 Unexplained Presence, and Joanna Walsh’s 2022 My Life as a Godard Movie―each consider existing works of art (mainly photographs and films) where the subjectivities of the people these writers identify with are not centered or carefully addressed. In fact, Black figures and female subjects are frequently marginalized or made into tropes. As a result, this art is often inhospitable to our three writers. But that doesn’t stop Campt, Bryant, and Walsh from inhabiting them and trying to accompany their sidelined subjects. As she does so, each writer locates agency and even resistance for the photographic and filmic subjects beyond what the original artist-makers intended. She also puts her writing in conversation with her own life and/or time.

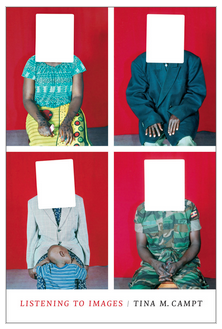

Tina M. Campt’s Listening to Images is the most academic of these three books. Campt lays out her book deliberately, providing a detailed summary in the introduction of how the three chapters and coda will examine overlooked photographs of the Black Diaspora. Throughout, she cites her sources, includes the terminology of other scholars, defines her terms, and generously illustrates her writing with accompanying images. She also incorporates back matter the others don’t, namely a bibliography and index.

At the same time as Campt is a careful and thorough scholar, she also explicitly defines her own positionality. She describes herself at the start of the first chapter as “…an African American feminist scholar of a certain generation―a generation educated in the 1980’s and weaned on the writings of a cadre of radical black feminist thinkers, who were among the first to claw their way into the university and make a place for others like myself…” (Campt 15)

Campt’s emphasis on the first person continues and develops as she dramatizes her numerous encounters with various photographs. She confesses her vexation at the way a group of ethnographic photographs of South African women categorizes and classifies them but also admits their dignity and introspection. She confesses feeling paralyzed at an invitation to pose in front of J. D. Okhai Ojeikere’s photographs of Black women’s hair and agreeing to do so despite her unease. She chronicles misremembering a photograph of a Black teenager just a year older than Campt herself. His arrest and incarceration helped form her own political consciousness as a young person.

One of the most affecting dramatizations comes in the book’s coda. Campt begins her discussion of a collection of Tumblr photos called #If They Gunned Me Down, Which Picture Would They Use? with this description of her viewing experience and desire to get closer:

It was a collection of photographs I couldn’t touch, and I’ll admit, I’m not really comfortable with that. I prefer to handle and touch photos as much (or little) as an archive or their owner will allow. It gives me a feel for the image, and the contact intensifies the impact and impression they leave on me. In this case, rather than gentle handling, I scrolled, tapped, and clicked in and out, and up and down on my trackpad…Having spent two years studying mug shots and prison photo albums, I couldn’t help but compare them to this very different archive of twinned images of the same individual posed side-by-side…(Campt 108)

Campt’s identity as a Black woman is clear from the start of Listening to Images. But by so often slowing down her encounters and narrating her feelings about seeing and often handling historical and contemporary photography, Campt provides space for a reader―a reader of any identity―to see slowly and make sense alongside her.

In Unexplained Presence, Tisa Bryant is a more circumspect host than Campt, and not every gesture is a straightforwardly friendly one. Her descriptions of film and other works of art are not always easy to follow. The book, what’s more, features no accompanying images. As Bryant explains in the preface, “In homage to Roland Barthes, I opted…to instead enter into the foxy realm of myths that images, signs, and metaphors create, and to bring you with me.” (Bryant XI) The table Bryant has laid Unexplained Presence is rich with offerings if only we can be brought along with her.

One of Bryant’s most striking gestures in Unexplained Presence is to introduce chapters with a quotation or a description of a historical work of art that will echo back later. A Black page trailing behind a fashionable lady in an eighteenth-century illustration echoes back in the young Black boys outfitted in powdered wigs and working as pages at a fancy charity event in a mid-twentieth-century film. The sexual relationship between a Black man and a white woman, oblivious to what surrounds them, in an eighteenth-century English engraving returns in a late twentieth-century English film. Émile Zola’s praise for Edouard Manet’s inclusion of a Black woman and a black cat in his 1863 painting Olympia reverberates in Bryant’s imagined internal monologue for a Black housekeeper in an early twenty-first century film when the character wishes for, “…a vision that does not require my flesh as scrim.” (Bryant 57)

The “presence” of Bryant’s title is not just the Black figures in European art who are present but not centered. It is also the present moment and the ways these oversights and caricatures in white depictions of Blackness―these patterns of marginalizing and othering―continue and continue. As a quotation from Theo Angelopoulos following Bryant’s last chapter offers, “The past is only past in time; in reality, in our consciousness, the past is present, and that which we call future is nothing else than the dreamlike dimension of tomorrow explained in the present.” (Bryant 161)

How, then, does Bryant bring the marginalized to the center? How does she point to recurring patterns of representation? One approach is to interrogate directors for their choices, like director Patricia Rozema’s decision to make slavery into a quickly glimpsed, barely audible presence in her 1999 adaption of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. Bryant mocks, “O, speak obliquely, if at all, of History and its slaves…It is wild, too wild. The mass cult of Austen wants it tamed…For there is no one alive now who can be held responsible for what happened then. For ‘it’…This is romance. Back to the time when we had it made. Who’s whose, we? Hush now. Don’t explain. Rozema, rabble-rouser, raises an eyebrow.” (Bryant 19-20)

Later, Bryant’s use of the second person requires that her readers step into the act of trying on racist ideas of Blackness, as Italian actor Monica Vitti does in a scene from Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1962 film L’Eclisse.

When before there was utter silence, now there are drums to accompany your gaze. Drums for every blink of your eye. Drums in the cut between your white self, seen, and this other sudden presence. The not-you. Cowbells and blackface. You’re magically done up in coal dust, gold coils around your neck…Unseen men chant in an unidentified language. No record plays; tribal sounds simply fall out of the sky. You begin to ‘dance.’ (Bryant 99)

Bryant’s use of “you” here directly implicates every reader, demanding, uncomfortably, that they imagine themselves behaving as Vitti does.

Most poignantly, Bryant speaks to or from the perspective of marginalized Black figures, especially women, as she does in her essay about Sammy and Rosie…Get Laid. In imitation but also subversion of the film’s title, Bryant calls this chapter, “While London Burns…Violet is Blue.” Addressing the Black female character who is left out of the credits at the end of the 1987 film, Bryant asks, “Violet, yard girl, what is your true meaning? Danny’s virility? (Is he yours?) Whose child are you?…Where are you now? Are you free to love, just not seen doing it? (Bryant 36-37) Reading Bryant’s book, I felt like a movie-goer sitting in the row behind Bryant talking to a friend or to the screen, eagerly trying to catch every word.

Joanna Walsh’s book, My Life as a Godard Movie, is the shortest and newest of the three books. Here, gender and age, not race, are the focus as Walsh watches and rewatches the early films of French director Jean-Luc Godard. As she explains on the very first page, Walsh is enamored with film and the negotiation between the seeing, framing director and the seen subject. “I like film,” she explains, “because the paint is human. So many paintings have been made about women by men, the women’s gaze only pigment the man has put there: on camera the woman is a real person and, no matter how much the director tries to turn her into a colour, there she is looking…” (Walsh 7) In Godard’s films, Walsh finds and admires again and again the hesitation and resistance of young women as they react to Godard’s men. As in Bryant’s book, familiarity with the films Walsh discusses is helpful but not necessary.

Organizing each chapter around a film and a related color―real or symbolic―Walsh begins to insert and assert her own life more forcefully as she moves from aspiring to be like a Godard girl to charting a new, middle-aged identity. If, in the first chapter, she’s a woman being told that she appears as though she were filmed in Eastmancolor (the color filmstock Godard used), by the beginning of the second chapter, she is telling us, “I watch films with a border of life round the edge, my life.” (Walsh 15) This chapter supplies that border as Walsh first tells us about her parents’ marriage and then finishes back in her own kitchen. It also introduces one of the techniques she will continue to employ in later chapters: an indented, italicized paragraph that offers reflection separate from the mix of criticism, biography, and memoir she presents in the main text. Musing on the way beauty, revolution, and violence mingle in Godard’s films, Walsh writes, “I knew it was unfair that only beautiful girls got the chance to appear, and unfair that violence destroyed them.” She concludes, “I wanted to have a revolution by revolutionizing appearance.” (Walsh 18)

Several chapters later, the indented, italicized paragraph becomes a space of confession. “Did I ever tell you I’m still alive because I went to Paris? Went to Paris, never having been there, but having a Paris to go to? Unhappily married (two words to stand in for so much), unable to decide to leave…I thought (two words to stand in for so much) of death. Instead of dying, I went to Paris.” (Walsh 29) In another chapter, she asks, “Can we have avatars that are not beautiful? Can appearance itself be defeminized? Not how would that look? but how would that feel?” (Walsh 43-44) Here, the use of italics signals that Walsh, again, is moving into an internal space of contemplation. By the conclusion of the book’s second alternative ending, though, Walsh is ready to move to outward address and declarative statements. “Beautiful girls, you have your fight and I have mine,” she asserts. “Our fights can help each other’s, but I cannot fight through identification with what I am not…I am not a Godard girl; I do not live in a Godard movie…It is time to switch off the camera. There must be other ways of making art.” (Walsh 85-87)

Works of art are negotiations between those who see and those who are seen. Tina M. Campt, Tisa Bryant, and Joanna Walsh all parse these negotiations in works of art made even more fraught by differences of race and gender. At the same time, each emphasizes her own experience and subjectivity, adding another voice to that negotiation and underscoring what it means for her to look now.