Excerpts from a memoir

by Robert Roper

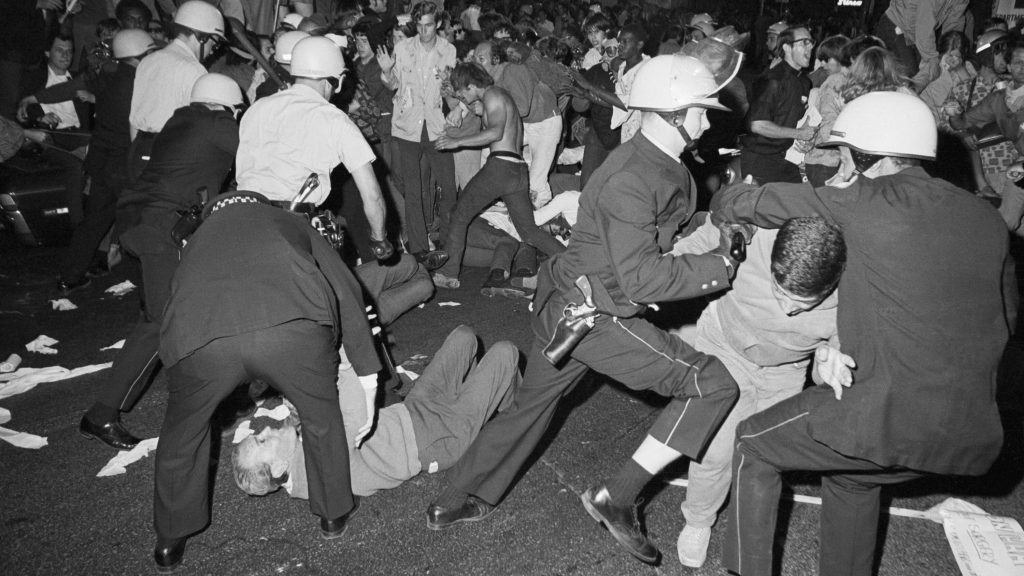

When I saw what was shaping up in Chicago, I had to go,mainly because I wanted to catch the action, but also to put myself on the line a bit. In the mythology of the event – Chicago‘68 – hordes of crazed youth descend on Mayor Daley’s broad-shouldered town in late August, for the Democratic Convention;the police, armed with truncheons and wearing baby-blue helmets, and just fed up to here, you know, with those flag-desecrating little snots, get badly out of hand. My first surprise,when I rolled into town with Brendan, my college pal, was howempty everything looked. The hippie hordes were hard to catchup with, were will-‘o-the-wispish. Lots of police on the streets,and these were the police of the just-post-Eisenhower era: fat-chested ethnic whites, strangers to the gym, big fellas, donut-eaters. When I ran from a couple of them later I easily outdistanced them, not because I was fast but because they were so frankly porky.

The reality was that the half million or so enemies of the genocidal war in Asia who had been forecast to show up, had mostly stayed home – careful crowd-counting indicated that only about 10,000 people made the scene, and these were not all longhaired troublemakers, by any means, they included also anti-nuclear moms and dads and church groups, and in the crowds I disappeared into, local teens always played a numerically significant part. These local boys – almost all were boys – did some of the craziest, most risk-intoxicated shit I’d ever seen. Like me they were there mainly for the kicks. They knew the alleys and backstreets and were good to follow if the police were lumbering toward you.

Daley and the Democratic authorities had alerted the country early, getting word out that there was going to be violence in Chicago, bomb-thrower, maniac-radical type violence. People decided to stay home, wisely. The violence that the students were planning to commit, it was said, included poisoning the city water supply, dynamiting gas lines to set white neighborhoods on fire, and putting LSD in the delegates’ drinks (would have been curious to see, maybe then they would have voted for Pigasus, the 200-lb. hog that the Yippies nominated).

When the sun went down, people broke up park benches and built bonfires – it was a chilly night, the whole week was rather cool, as I remember. Early on I heard, although I did not see, Allen Ginsberg, the Beatnik poet, chanting “Om” in a chorus of fellow-chanters, trying to channel the crowd’s energy, bring us back from the sinister edge. It sounded insipid to me. Violent exhorters sprang up, young guys with powerful throats, charismatic writhers and concrete-tossers, dangerous-looking, fantastical-looking in the firelight. The cops surged among us,thwacking right and left. Then retreated, sneering. Their pretext was the park curfew, that by law everyone was supposed to be out by 11:00 p.m., but we were standing against that, we protesters, we wanted the park for our own purposes, maybe to sleep in. Occasionally there would appear someone at your elbow, usually a slightly older guy, giving you a few hurried, rehearsed words on affinity-group tactics – these were SDSers, I learned, advising us to get out of the park and rampage in the nearby streets, in small groups. The goal was to avoid mass arrest

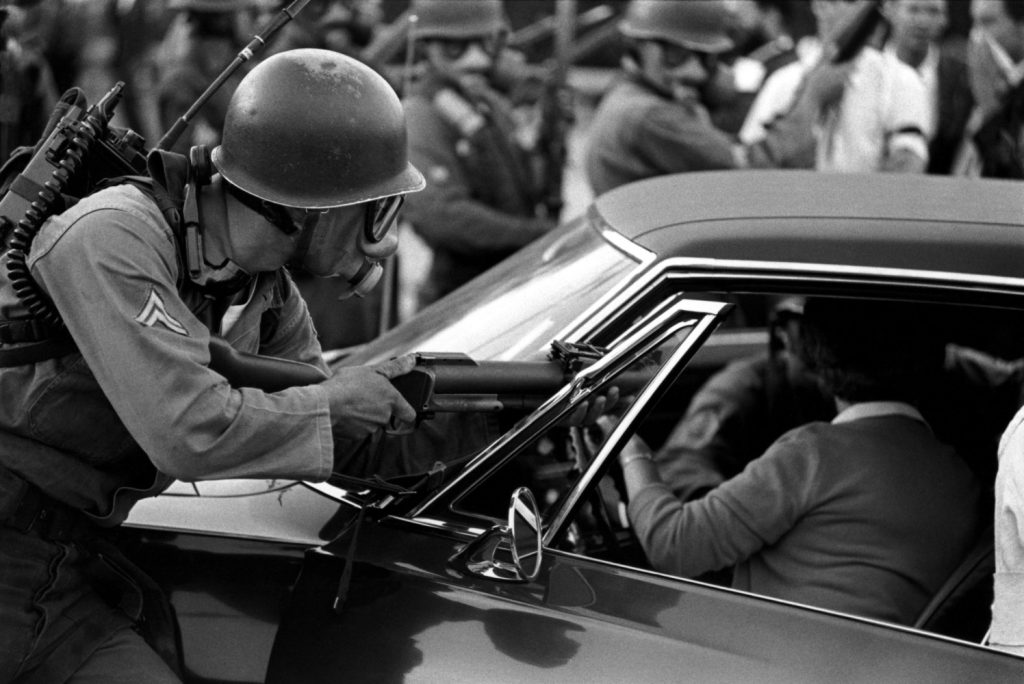

Reporters were everywhere. Just like us they were being whipsawed by the surges, were trying to keep their heads up, stay afloat. Some looked scared out of their minds, and I wondered if I did, too. I sort of wanted to be elsewhere. It was all very interesting, but the other side had the truncheons and the paramilitary training, they knew how to form up and charge – the SDS line on small groups, avoiding arrest, suddenly appealed to me. Rocks “got thrown.” Half-full beer cans, chunks of bench. I saw a couple of cops set upon by a small mob, which kicked them around a bit. Other police lumbered to the rescue, drawing blood and breaking some cameras. Curfew hour passed. It was not a scene of combat, of course, since guns were not being fired and you could still wriggle out if you just shut your mouth and walked away, but it was as close as I’d ever come to an ungoverned street battle, and it did not make me happy. Something in me did not rejoice at the violence, not on the grounds of an American place. I felt angry and mistreated as a young, tormented idealist, but then I had always been angry. Teargas canisters exploded, loaded with extra-noxious CN gas, and police reinforcements kept arriving – it seemed completely unfair. Some of the cops were strapping young fellows, excited local guys out kicking ass with their buddies. We longhairs were exercising our First Amendment rights while they were getting into a kind of orgy.

Helicopters thwup-thwupped above. I suddenly wanted to be up there, too, gaining some perspective. I weaseled away, feeling not very ashamed at the time, though now I do. I hadn’t known how much they hated us – I really hadn’t known.

Onward. Onward to my personally-troubled summer of ‘69.

I had been to Chicago. Now I was sheltering from life as a student, a practiced strategy, although I knew I would never become a professor. Each day I woke up afraid of my own mind, excited but in a bad way, aware of a thrilling world out there that I wouldn’t let myself have. The blue skies continued to upset me. A poster on my wall still filled me with dread – a representation of happy cowboys, of all things.Fall came and I managed the French test. In December two friends took me to the concert at Altamont. We were so far from the stage that the sound arrived on a half-second delay, and the musicians were tiny, posturing action figures. Normally I would have disliked this scene, a giant mob of people of roughly my own age lying around on blankets, loaded on wine and psychedelics, but on this day the nearness of my longhaired brothers and sisters did not annoy me, in fact it sort of cheered me. No fights broke out where I was, everything was peaceful and patient. Down closer to the stage people were packed in like gerbils in a bowl, feeling the crush of the gerbil-mass above them, but on the heights we were sharing water and smoke, joking about the impossibility of getting to a bathroom, and the giant swarm – 300,000 people it was later reported – generated mostly good vibes.

Mid-afternoon, after Jefferson Airplane’s set and when Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young were about to come on, my friends and I took some reputed psilocybin, despite the late hour and my personal fear that this might tip me over into permanent raving psychosis. The drug came on gently, beneficently. I was mostly lucid, noticing a lot of interesting faces, and it was almost like an ordinary day. My friends decided that we should leave. Okay, forget the Rolling Stones, the main act which hadn’t come on yet. We found our car after comical missteps. The drive back to Berkeley was wonderful, increasingly blissful. We were headed west, into a dusty sunset, a magnificent display of roseate hues on this mild winter day. And this is what we breathe, I told myself, these colors, this magic atmosphere. I tried to tell my friends. I was sitting in the backseat of their VW, and as soon as I started to speak they started laughing uncontrollably, because they already knew, they were breathing it too, at least that’s what I thought their laughing meant. Motherfucking crazy sunset.

Back at my apartment, a small party was underway. Greta and a few of her girlfriends, among them the flirty Irish sisters I particularly liked, the McCarrans, Monica and Maureen, were there, and I met their new boyfriends, who, wouldn’t you know, were a pair of similar-looking brothers, as they were similar-looking sisters. What a wild world! Greta had made some food but I couldn’t eat any, I was too high. Monica put on a record that she’d bought just that day, “Crosby, Stills, & Nash,” which I’d heard cuts from on the radio but never the whole thing through. The coincidence of having just left the concert where CSN plus Y were about to play, only to walk into my apartment and hear the chunky opening chords of Stephen Stills’ “Wooden Ships” – and what a song that was, wow, wow – struck me as fascinatingly strange.

I tried to tell Monica about the sky, the insane colors, realizing, and telling her that I realized, that this was a laughable cliché, to be high and raving about the sky, and she listened for a few seconds and then led me into the kitchen, telling me to eat some lasagna.

This is what people have always made much of, vision, ecstatic personal vision. Not intellectual “vision,” but inward-and-outward vision. I was joyful to get it straight at last. And this was my own bit of it. Okay, it came out of a pill that my friends had bought from some guy on the street, it was chemically juiced, my vision, it wasn’t like Paul on the road to Damascus, a thunderclap out of the god-heavy heavens, but it had a sweet conviction, the flavor of the moment and of me, such as I was, flawed seer that I was. The song was still ongoing, it was a long moody one, and I caught a phrase I especially liked: something-something “anguished cries.” You didn’t run into phrases like “anguished cries” in rock lyrics usually. Stephen Stills had been reading some poetry, I figured, maybe some Rod McKuen, maybe some Wordsworth. I imagined him living a life not entirely untouched by anguish, despite the rock-star prerogatives. I was thrilled that he’d written a song about it. Good for you, Stephen. What a miracle to write something good.

One other incident from that time of trying to wake up, to come to the world with more desire than fear: I dropped out of school. Gave up the nice stipend. I’d always dreamed of shipping out, having adventures like Melville and Conrad and other saltwater pals of mine, and I poked around the local hiring halls, discovering that you could get a berth on a merchant ship, but you had to be in the seamen’s union first, the powerful SIU (Seamen’s International Union). They wouldn’t let you in the union, though, unless you already had a berth on a ship, so the only way to get work was through some trickery, come Catch-22 business, and nobody would tell me who to pay off.

I mentioned the impasse to my father. He volunteered to speak to someone in the Maritime Administration, which was an agency of the Commerce Dept., where he still worked. Somebody over there might take pity, tell me what was what.

A few weeks later, I received an invitation to an informational meeting. The offices of the Maritime Administration in the West were in a big gray building on Mission St., San Francisco. To my surprise, the meeting wasn’t with an underling but with the Acting Director of the agency. He was a fullback-shaped old man with a severe crew cut, dressed in a dark blue uniform the day I came in. He had a grim expression and looked like an admiral, with gold service stripes on his sleeve and a lot of chest candy.

of the seamen’s union.

His desk, with model ships on it, was as big as an aircraft carrier. The office itself was unusually long and had windows offering a vast view of San Francisco and the Bay. The admiral was writing something. I had spruced up for this encounter, brushing my hair and putting on a clean shirt, and maybe I’d even polished my boots, the ones I’d worn in the Sierras. Apparently my first lesson in Merchant Marine deportment was to stand for as long as it took for the admiral to look up from his desk and deign to notice me. Okay – I could do that.

He looks up. Quickly looks back down. Writes some more.

Looks up again. Pushes back from the deck of the carrier. Something’s terribly wrong. He can’t get a read on me, can’t make sense of me. Shakes his bullet head.

“How did you get in here?”

“Your secretary said to go in and wait.”

“Okay.”

Keeps looking at me, though. Finally, curses. I distinctly heard the word “shit” out of his frowning mouth.

“I don’t know your father. I’ve never met the man,” he said, “but I can tell from his letter that he’s an honorable and conscientious person, doesn’t like asking for special favors, but he’s your father, so he’s caught, he has to. Maybe he doesn’t know what’s become of you out here. Maybe you’ve been out of touch. Are you high? Are you high right now? Because I’ll tell you, you must be out of your fucking mind to come in here looking like that, like I don’t know what, a piece of hippy garbage. Good God. Look at you. If he could see you he’d be ashamed, I would bet my life on it. But it’s you that should be ashamed.”

Oh, well – there went my nautical adventure. I’d considered a haircut, but decided to come as myself. A mistake, apparently.

He wasn’t finished: “This letter,” and he brandished my father’s one-page note, on which I could see two short paragraphs, “says that you’re interested in the merchant service, that you want to get on a ship. The merchant service is something I take seriously. I’ve given my life to it, as other men have given theirs. I bet you didn’t know we wore uniforms. We do, we officers do. Many men have died serving their country as merchant seamen. In World War Two nine thousand five hundred twenty-one men of the Merchant Marine died on cargo ships, mostly in the North Atlantic, and a total of two hundred forty-three thousand served all over, many going down in the Pacific. Nine thousand out of two hundred forty thousand gives the highest casualty rate of any of the armed forces, including the Marines. That’s the tradition that you propose to assimilate yourself to. Coming in here looking like a fucking degenerate, like a hobo, a derelict – good God, you disgust me.

“Okay,” he went on, “I’m going to be straight with you. I could get you a ship, but I’m not going to, I’m not going to lift a fucking finger. I’m sorry if your father in D.C. doesn’t like it, but that’s the way it goes. The fact is you make me sick, you and your kind. You make me fear for my country, more than any foreign nation or possible war, and I’m a man who served in two wars, I know about war. We have birthed a generation of parasites, of poisonous vipers in our breast, in sinu viperam habere, as the saying goes. Get the hell out of here. Before I come over there and smash your smirking face.”

The elevator down to the first floor deposited me in one of those governmental lobbies that I knew well from my boyhood, when my father would sometimes take me to work with him at the Commerce Department building on Constitution Ave. Nowadays a federal lobby has a defeated air, as the underfunded site where the mere business of the people gets transacted, but in late ‘69 there was still a quality of moderate democratic ease, and this lobby had a functioning cafeteria full of snack-eating visitors, a news kiosk displaying a dozen American newspapers, a shoeshine stand, a cloakroom with an attendant, and a bank of phone booths. Two guards were welcoming people at the front door and giving them directions if they needed them. There was a barbershop. I bought a copy of the L.A. Times, which I’d heard was a good paper, and considered my options.

When I got back up to the twelfth floor, I told the receptionist that I’d left my briefcase inside. The admiral was still at his desk. Again, a minute went by before he so much as looked up – he was writing a letter, using a heavy-looking fountain pen.

Looks up again. You again? he seems to think. I handed you your head, but here you are again. Then his expression softens. Unbelievable – you never know. You just never know. Shakes his head, sort of smiling.

“Okay. You got me, I guess.”

I waited.

“Looks a lot better. You might try shaving, too. And bathing.”

He stood up from behind the aircraft carrier. Held out his hand for me to shake. I walked over.

“Ever been on a ship?” he asked. “An ocean-going ship, a real one, navigating the open seas?”

“No, I don’t think so.” “Well, it’s quite an experience. It’s awesome, if you consider it in all its dimensions. ‘It is not down on any map; true places never are,’ Melville said of the undivided sea. The Greeks weren’t the first to venture forth, but they got the poetry of it, and that was the birth of civilization, right then. ‘The wine-dark sea.’ That well-known phrase still retains some of the magic. You haven’t read Homer, I’m sure, why would you? They teach Ulyssesin the fancy colleges but the Odyssey is forgotten, let alone the Iliad, which I recommend to you, not only because it’s a personal favorite of mine, but because it’s the greatest of all the classics of epic verse. You have a lot of time on a ship for reading. The truth is you don’t have much work as a bedroom steward or an ordinary seaman, your duties are very narrowly defined and the mate will get on your case if you work too hard, because you’ll be showing up the others. It’s a good place to begin to educate yourself. Don’t drink too much, drink is the bane of the sailor’s existence, that and a disrupted family life, given that you’re at sea for months at a time. But don’t worry about that now. You’re young, you’ve got a whole story ahead of you. The wine-dark sea. It’s still out there – the wine-dark sea.”