If 19 Turned Out to Be 75, I Don’t Mind

Eric Darton

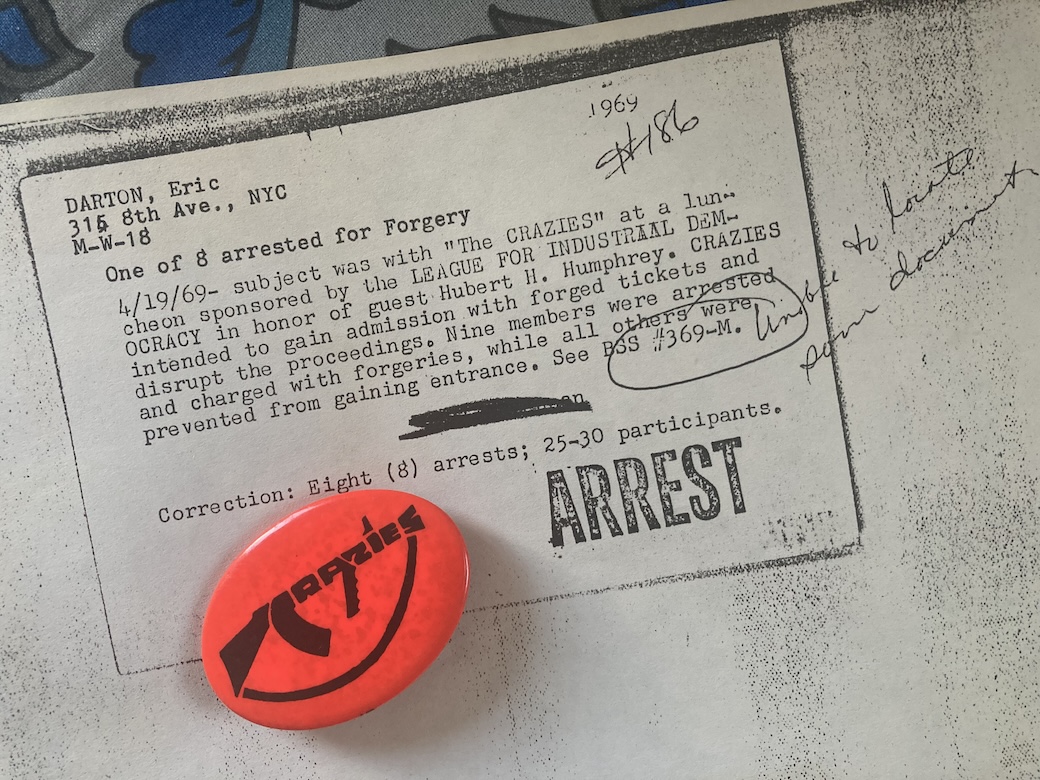

Copy of a NYPD Intelligence Division file card obtained by the author under the (Barbara) Handschu Decree of 1985.

—For Chris Sawyer-Lauçanno

In the midst of his seventy-fifth summer, his nineteenth resurges so powerfully it no longer feels past, rather twined into a single concurrent Now.

How does such a thing happen?

What cues from outside: a familiar taste to the morning air, a face that reminds him of a former lover, a streetscape that still resonates in some way with its prior lives – what stimuli create a channel along which not just memory, but a sense of immanence itself, may travel?

*

Summer of 1969 and E. is stone in love. Living in a one-room commune on 10th near Waverly, just west of the Women’s House of Detention and Sutter’s French bakery. Squad 18 of the FDNY was, and remains, diagonally across the street.

In mid-June he’d taken his first acid trip, and not long after, unintentionally, but enthusiastically, participated in the Stonewall Riot. July found him working at Grove Press on Hudson Street, just south of the headquarters of NYPD’s Bureau of Special Services, more familiarly known as the Red Squad. Passing by in the morning, he’d occasionally spot Finnigan and Judge, the pair of detectives assigned to surveil his little insurgent band, heading into their office, coffee and donuts in hand.

Speaking of police, the local precinct was, and is, the 6th, on Charles Street. There, he is reliably informed, the cops have posted an 8×10 – taken by a press photographer who later surfaces as an informer – on one of the locker room walls. The picture shows him and his communards, arms round one another’s waists, naked, yes, with guns. Naked, that is, apart from the Crazie buttons above their left nipples which look for all the world like they are pinned through living flesh, but nah, they’re just stuck on with doubled-up tape.

Crazies: the name of the group E. belongs to, though there is really no enrolling – it’s more a matter of affinity. Ah, but for what? And who?

But back to love. His fellow communards are, understandably, not pleased by the sounds that issue from the sleeping loft where he and his lover spend the night. She has convinced him, and her experience greatly outweighs his, that he is, by far, her best partner to date. She also works at Grove Press, where her job is to handle correspondence; his job includes opening the mail. Comrades V. and M. work in the stock room and editorial office respectively.

Once a great avant-garde publisher, Grove, familiarly known as Grope, has become, essentially, a porn mill. Later, it will reclaim some of its literary cred, but at present, a great deal of cash gets mailed in from hither and yon in the great heartland for books with titles like Joy in Impalement and Prayer Mat of Thighs.

A born gonif, E. only steals a fraction of the bounty, stuffing a few envelopes into the waistband of his bell-bottoms and opening them in the loo where he pockets the proceeds. Then he gives all the envelopes, cash-filled and pilfered alike to his lover; she sends everyone their books in plain brown wrappers and Bob’s your uncle. The company takes a hit, but the trade’s so lucrative no one bothers doing inventory.

He delights in spreading his largess around among his comrades; his official salary is $70, but he’s taking in an additional $300 or so per week – bringing his total income almost on par with an aquaintance who is a junior partner at a “movement” law firm. Indeed he feels quite grand, treating the crew to steak dinners out on a regular basis.

Sadly, the Grovey train ride lasts but a short while. No, he is not caught with his hand in the till, rather the proximal cause is V., who, incensed at the degrading conditions of his employment, whips out a Magnum Sharpie in a fit of pique and tags a protest on the building’s posh, marble entryway. The graffiti consists of a stylized clenched fist, with YOU’RE A PIG, MYRON scrawled beneath it. Myron is their boss, and supposedly a fellow Crazie. But the graffiti-ist, is correct, Myron is a pig, a real martinet and management flunky, and since the style of the graffiti is so distinctively V.’s, he is fired on the spot. Myron leans on E. to scrub off the offending message, but hell no. What’s a brother to do but quit in solidarity?

Thus ends his association with publishing, for the moment. But the Crazies and the commune go on, and in addition to the Myron graffiti, V. is also the author of the previously mentioned oval Crazies button. It’s a horizontal oval, about three and a half inches wide by two high. Against a dayglo blood-orange background the word Crazies is printed in black “psychedelic” lettering that causes the letters to merge into the silhouette of an AK-47. Genius manifests in myriad ways.

As in the wondrous idea someone has, that same summer, for transforming every New York City mailbox into a Viet Cong flag. Simple: the bottom halves of the mailboxes are painted blue, their tops red. All one needs to do is stencil a yellow star at the horizon where the colors meet et voilà. It’s a Federal crime, but lookouts are posted, so no one ever gets caught.

As for the Crazies, they appropriate their name from a derogatory mention in the Village Voice, reporting on a theatrical disruption in which E. participated, one of many involving, nudity, pigs’ heads on platters presented to insufficiently radical pols and other dignitaries, and similar droll thespianisms. “They’re a bunch of crazies!” the Voice reprehended, and again, all it takes is capitalizing the C, same as how the Shakers and Quakers and Ranters got their sobriquets. Sure, why not?

Upon assuming their identity, the Crazies’ first act is to liberate a patient from the Bellevue Hospital psych ward. Of course this is all the better staged. So V., who looks quite mad anyway, gets trussed up in a straightjacket and makes his “escape” from the front entrance, fleeing fake, but credibly uniformed guards. The press, informed in advance, is on the scene, and the image runs as though it were fact become legend: V. dashing into the arms of his fellow Crazies, who bear him off into the noctilucent wilds of Fun City.

*

Just one more anecdote – I almost said antidote.

Woodstock happens. E. doesn’t go. Nor does his lover. Nor his other communards. Rather they host a swinging party in their half-basement apartment with a little concrete patio out back which is attended by several members of the Young Lords. Comrade M. cooks up a pot of his notoriously photonic chili con carne, but something’s off so a bunch of people end up vomiting in the kitchen sink. Which, as it turns out, is plugged up. Hot fun in the summertime.

Next week they score some very fine acid. So fine that deep in the night everyone comes down with insatiable munchies. And being the least wrecked of a very wrecked company, he volunteers to truck over to the Smiler’s deli on Sheridan Square – which they called Frowners because of the surly counterman – and score a tub of Whip ‘n’ Chill with which to satiate the masses.

Outside, in the sultry night, lies good old West 10th Street, mais complètement transformée. To the left, toward Greenwich Avenue, a dozen or so men in wigs and skirts make a heroic effort to turn over a crosstown bus. To the right, the cavalry advances, or at any rate a unit of the TPF, the tactical police force, mounted on their majestic Morgans, batons at the ready and wearing their signature egshell blue riot helmets. My god, he thinks, this is the most beautiful color that could possibly exist, plashed as it is by red and white lights from the police cars following directly behind the noble steeds. And all of it, including the probable bus inversion, seems very stately indeed.

E. beats it back inside and informs his comrades of what is going down as best he can, sounding, to his own ears a good deal like Donald Duck, and of course, they all rush out to see for themselves. And yes, the Tenth Street Crazies collectively rise to the occasion and spend the night in joyful celebration of what will become known as the H-hour of Gay Liberation. Simple as lighting up a full trashcan with “Every Litter Bit Hurts” writ on it.

For three days, the West Village remains an anarchist republic. But that first night is the best. Early in the new morning, the cops having been driven from the field, he crunches through the crystalline shards outside the trashed Manufacturers Hanover branch at Sixth and Waverly, whose glass bricks had so fascinated him as a toddler being pushed past in a stroller on the way to Bank Street School, which isn’t on Bank Street any more, nor are any banks if ever there were.

Nearby is the site of his first and only spanking at around age three. His mother, having elicited from him a solemn vow to stay just where he was on the sidewalk, went into a tailor shop at the corner of Gay and Waverly Place, and came out to find he’d wandered into the street. So with tears in her eyes, indeed streaming down her cheeks, she administered the requisite punishment for breaking a promise.

And who knows what she must have gone through when he’d grown old enough to be chased by cops with truncheons, get shot at on rooftops by the same constabulary, breathe in CS gas here, there and everywhere, and whenever a busted brother or sister could be pulled back from their clutches, have at them for all he is worth.

But she knew, too, that there was a war to stop, and the dignity of everyone to uphold, and kids to be fed, and old folks looked after, and when their hour came, seen properly off the planet. She knew all those things and also that, despite his wildness, he loved her, and would care for her if he survived.

*

A deep breath. And on the exhale:

We’ve been soaring to the sounds of Jefferson Airplane: You are the Crown of Creation; Dark Star from the Grateful Dead; the Chambers Brothers’ Time Has Come Today; Janis: Take another little Piece of My Heart, and inimitable Dr. John: Walk on Guilded Splinters. It’s closing in on two a.m. and you are flying with Alison Steele, the Nightbird, till dawn . . .

And the needle drops on “Lay Lady Lay.” The black spiral spins, Dylan’s verses go round until here comes the refrain, in stereo, as if he’s standing between two speakers opposite one another in a room fifty-six years wide:

Why wait any longer for the world to begin?

You can have your cake and eat it too . . .

* * *