Eric Darton

Excerpt from a work-in-process on the novels of James Baldwin

Summer Solstice, 2023

Jimmy, I’m sitting here in on the rim of the circle, watching the fountain spray and thinking that Washington Square Park deserves better musicians. Like Sonny, or Rufus Scott; musicians whose ears are tuned to the hidden waters, coursing underground: the southwest flowing spring called Manetta by the Lenape. It begins up near Madison Square and disembogues into the Hudson around Canal Street. Long paved over, the only visible proof of the Manetta’s existence was what bubbled up into a little fountain in the lobby of 2 Fifth Avenue – the big white brick apartment block that went up after you left for France, but before you wrote Another Country. A few years ago, the plumbing busted, though a plaque identifying the spring remains on the lip of the dry marble basin.

Once this park and its surrounding terrain was known as t’Erf van Negros, or Land of the Blacks – the Dutch name for the area which they allowed certain freed African slaves to settle and farm, to serve as a buffer between the New Amsterdam settlement and the Lenape to the north. Which situation changed when the English took over and re-enslaved the blacks.

A lot of Manetta’s trickster-spirit waters have passed beneath the park since you left the states, two years before I was born. And since you died the trees here have blossomed thirty-six times. The Hanging Elm’s still soaring over the northwest corner. Hopefully it will outlive yours truly.

I learned recently that the graywacke stones in this circle were first cut for a fountain at the southern entrance to Central Park. Like you, and Jack, it migrated here.

Heaven round, earth square, so they say. In traditional Chinese cosmology, the circle is identified with the dome of heaven and the human head; the square is associated with earth, represented by our feet placed side by side. It is in our bellies that the two polarities meet and their energies intertwine.

And plus ça change: there are red-tailed hawks here now, which there weren’t in your day, nor when I was growing up. Still, despite the raptors, a multitude of pigeons remain. The small gray female who just perched next to me on the rim of the circle doesn’t seem to mind the wetness of the fountain’s spray. Apart from the iridescent purple round her throat, her feathers are a fairly typical range of grays. But she’s got the reddest legs and feet I’ve ever seen on a pigeon before. Chinese red, the same color as the Village Cigar shop – you knew it as United Cigars – on Sheridan Square.

August 2

A shotglass libation of scotch poured into the fountain in your honor. Today would have been your big ninety-nine.

Which cosmic event may have brought at least one really good musician to the park this morning – one I’ve never seen here before. A violinist – it turns out his name’s Josh – heavy-set, about twenty-five, wearing short dreadlocks. Lovely intonation. Don’t know what he’s playing, but it has to be Bach.

Miracle of miracles, Josh has got no sonic competition. No Alex bellowing “One is the loneliest number,” slamming away on his beat-up spinet. No youthful free jazz or bebop combos, no formulaic saxes, no lead-footed, heavy-handed drummers.

Even the wandering mad have fallen silent in this rare moment. Lawns and paths overhung by locust trees, bursting in bloom like there’s no tomorrow. Scent of new-cut grass.

In the temperate months, in addition to serving, with limited success, as NYU’s quad, the park reverts to a kind of open-air Bedlam, albeit replete with music, trees and flowers, whose fauna include pigeons, squirrels, sparrows, grackles and rats. At times its primary human function appears to slide between tourist destination and emphatically non-rehab drug facility.

Surely capital makes its home here in several forms of trade, and with a vengeance in the real estate surround. Yet in some essential way these acres remain a zone apart, a sovereignty of unspoken consent: another country.

For years now, I’ve come here most mornings to practice Ba Gua Zhang – a Chinese internal martial art that embodies the interpenetrating polarities of heaven and earth, and the intertransformation of fire and water. Nor is it lost on me that these are the polar forces that animate your work.

We’ve encountered one another before, Jimmy. Back in the mid-70s, when I drove a cab, I mostly worked the evening shift: four in the afternoon to four in the morning. Given that I’m not a night person by temperament, I almost always came to the point of exhaustion somewhere around two a.m. Once, cruising down Seventh Avenue, I fell asleep at the wheel, just for a second, but long enough to nearly sideswipe another cab. So I pulled over at Sheridan Square and walked around trying to wake myself up. Then, for some unaccountable reason, entered United Cigar.

I recognized you right away. We were, aside from the clerk, the only people there at that hour. Amidst the newspapers and magazine kiosks, we made eye contact. Your gaze reminded me of how the leader of pack of wild dogs regarded me once when I crossed their path in the woods of Vermont: partly wary, partly speculative. As if trying to determine not just my potential vulnerability or threat, but my nature as an animal as well. There was something, too, in your look which signaled I know you. Yet how could that be, given that we’d never met? It strikes me now that at the time I was twenty-five years old – the same age as my my father when you knew him. And yes, it’s generally conceded that I look a lot like him. So at that moment, did you first think: Jack! And then But no, can’t be – that was thirty years ago. Or did something entirely different cross your mind?

For my part, I had the impulse to greet you as if I knew you. To say I admired your work. Explain that I was, indeed, Jack Darton’s son, though hopefully not as much of a Jekyll and Hyde. In the event, as I so often did in those days, I let the opportunity pass. Nor did another chance arise for us to speak, embodied.

If one lives long enough, one gets different chances. Perhaps the nature of chance itself mutates. For years I wondered about what it would be like to talk with you about the thoughts and feelings evoked by your novels. Particularly after, in my late thirties, I began writing. And then, of course, there’s another reason for us to have a conversation: that shared figure in our histories, a man turned to a phantom: Jack – your lover, my father.

But that said, I might never have thought to address you directly, had I not felt your presence, sitting beside me at the circle’s rim, both of us noticing the color of the pigeon’s feet.

And we laugh – from our very depths. What else is there to do?

August 3

The next steps are hesitant. Why, I’m not sure. It’s your novels I want to talk about, and not least Another Country. Not because they require elucidation. Nor because they speak inadequately for themselves, but because, amidst the body of your writing, I have sensed in their pages a consistent articulation and reworking of what seems your overarching and underlying subject: the nature and effects of the struggle toward love; love’s perilous – you would say “menaced” – achievement; love’s failure to cohere.

You wrote, and said publicly many times, that there is no safety in this world. That all is contingent, at risk, and that the ticket always comes with a price.

Yet your books are populated by vivid manifestations of the human spirit; by people who, foresaking safety, can and do attempt to love, at whatever the cost. And these characters exist alongside those so damaged that they cannot form a self capable of acknowledging another. Often your narratives trace the paths by which the presence or absence of love plays out in relations among adults. But to my mind, your eye is ever upon the physical and pychological survability of children.

A writer of my generation created a series of novels which, however different in a thousand ways, have something essential in common with your own. Her protagonist is a young wizard who in infancy survives a murderous assault. Harry Potter lives because his mother protects him at the cost of her own life. The young man goes on to struggle with astonishing vicissitudes – literally fantastical, yet psychologically and emotionally truthful – to become, eventually, that rare and exceptional creature: a conscious human being.

I had been in the habit of reading these books at bedtime to my daughter who, as of September 11, 2001, was nine years old. When we finished that evening’s chapter, I pulled down the shade on the plume of smoke billowing two miles south of her bedroom window and turned out the light. I was about to shut the door when I heard her ask me if things would be alright.

I said I didn’t know, but that her mother and I would do everything we could to protect her. To which she replied, as I turned out the light: They can’t bomb our love.

I’ve been rereading the Harry Potter series, and often feel a resonance with your novels. To distill things, I think Rowling’s intent was to inculcate children with the idea that the only protection in the world is love and that it must be cultivated at any price, and take precedence over any and all other propensities, particularly fear. I believe your intent, consciously or not, was to demonstrate to your readers, the necessity of love for their children – and by extension, all children. And, conversely, to show the tragic consequences of a disruption in the child-parent bond. Or its distortion into some soul-poisoning form. I do not know of any writer who sets out the question of love more urgently than you do.

I look at myself in the mirror. I know that I was christened Clementine, and so it would make sense if people called me Clem, or even, come to think of it, Clementine, since that’s my name: but they don’t. People call me Tish. I guess that makes sense too. I’m tired, and I’m beginning to think that maybe everything that happens makes sense. Like if it didn’t make sense, how could it happen? But that’s really a terrible thought. It can only come out of trouble – trouble that doesn’t make sense.

Today, I went to see Fonny. That’s not his name, either, he was christened Alonzo: and it might make sense if people called him Lonnie. But, no, we’ve always called him Fonny. Alonzo Hunt, that’s his name. I’ve known him all my life and hope I’ll always know him. But I only call him Alonzo when I have to break down some real heavy shit to him. [If Beale Street Could Talk, pp. 3-4.]

The fountain’s spray is blowing southeast today toward where Beauford used to live, before NYU cleared those blocks for housing and the gym. It was from his loft on Greene Street that, on a balmy morning in May, 1947, Beauford walked downtown to the Municipal Building with Bea and Jack to be the witness at their wedding.

The alto sax is back, saying nothing with too many notes, emphatically. Down on the path next to the grassy rise where I’m working out, a guy who looks like a combination of Vivaldo and Jack pedals by on a Citibike. He doesn’t glance my way – he’s on a mission. So it seems I don’t have to make anything up, the synchronicities just keep rolling out, and in. And why not? In a world running on historical empty, it’s not surprising to find so many ghosts, like Malcolm’s chickens, winging their way home.

And he looked at me, that quickening look he has when I call him by his name.

He’s in jail. So where we were, I was sitting on a bench in front of a board, and he was sitting on a bench in front of a board. And we were facing eachother through a wall of glass between us. You can’t hear anything through this glass, and so you both have a little telephone. You have to talk through that. I don’t know why people always look down when they they talk through a telephone, but they always do. You have to remember to look up at the person you’re talking to.

I always remember now, because he’s in jail and I love his eyes and every time I see him I’m afraid I’ll never see him again. So I pick up the phone as soon as I get there and I just hold it and I keep looking up at him.

So, when I said, “– Alonzo–?” he looked down and then he looked up and he smiled and he held the phone and he waited.

I hope that nobody has ever had to look at anybody they love through glass.

And I didn’t say it the way I meant to say it. I meant to say it in a very offhand way, so he wouldn’t be too upset, so he’d understand that I was saying it without any kind of accusation in my heart.

You see: I know him. He’s very proud, and he worries a lot, and, when I think about it, I know – he doesn’t – that’s the biggest reason he’s in jail. He worries too much already, I don’t want him to worry about me. In fact, I didn’t want to say what I had to say. But I knew I had to say it. He had to know.

And I thought, too, that when he got over being worried, when he was lying by himself at night, when he was all by himself, in the very deepest part of himself, maybe when he thought about it, he’d be glad. And that might help him.

I said, “Alonzo, we’re going to have a baby.” [If Beale Street Could Talk, pp. 4-5.]

When I get freaked out by what I’m writing, I think of a life-sized diorama in the Asian People’s Hall at the Museum of Natural History. The scene shows the interior of of a Siberian log dwelling in which a masked Yakut shaman performs a healing ceremony on a sick woman lying on a bed against the far wall. The scene is mostly in deep shadow, but the delirium in the stricken woman’s eyes is heightened by the glow of simulated firelight. The shaman kneels next to her, beating his drum and chanting. These two central figures are so dramatically posed, that one might easily miss a third person crouching off to the side. In his hands, this man holds a chain, whose other end is is looped around the shaman’s waist. Patiently, the attendant waits for any sign that the shaman – who has entered the spirit realm in order to drive the sickness from the woman’s body – has himself been overwhelmed, and stands in need of rescue.

Never let Rescuer Number One become Victim Number Two. That was one of Tom Demattis’ axioms. Born in Brooklyn, Tom had done two tours as a paramedic in Vietnam, then made a career riding an ambulance in the city. An exemplary survivor, Tom was also hands down the best teacher at the EMT course I took in the summer of ’85.

Jack had one grandchild: my daugher Gwen. She was born on Bastille Day, 1992. I caught her as she essentially leapt into this world, in an upper room birthing center in Saint Vincent’s – the same building where I’d done my required hours in the ER seven years before. Still dazed by the wonder I’d just witnessed, I dutifully shadowed the nurses as they took Gwen for evaluations and immunization, rolled black ink on the sole of her foot to stamp her birth certificate – then returned her to her mother’s side. Watching my two beloveds dozing together in a kind of unbelievable peace, I felt suddenly ravenous and headed down to grab an omlette just across Greenwich Avenue at Chez Brigitte. I hadn’t been outside during the eighteen hours of Katie’s labor and I walked through the sliding doors into a wall of midafternoon heat.

Lots of traffic coming downtown on Seventh Avenue, but I saw a gap and gauged the risk. Like Jack, I’ve always been fast. And I almost sprinted, but for the fact that the hard drive icon on my interior desktop had suddenly changed names. Formerly it had read Eric and now: Gwen’s Dad. So I thought, It’s only sweat, and waited at the curb until the light went green.

Who was holding your chain, Jimmy? It sounds like Jack was, at least for some of 1944. Christ, what happened?

The truth is, Jimmy, I have no one besides you to share these pages with as they roll out. At one time, I might have shown them, even in their early drafts, to Joe Macdowell who was, among other things, a great appreciator of your work. Truly, there was never born a better, more engaged and discerning reader than Joe. For a time we were very close. But he and I – like you and Jack – went our separate ways, and in our case, it was over the issue of a child’s protection from abuse.

There are others, too, who would look beneficently upon this process. Not least, Norman Riley, a drummer, like Rufus / Eugene, and a man with music in his blood. He would have gotten it, I’m certain. Norman’s gone now, too young. He didn’t jump off the George Washington Bridge, just bombed his lungs with cigarettes.

So for now it’s down to Me and I. Me is out there in the realm of the spirit, while I is holding Me’s chain. Just in case.

I don’t know how you managed to carry all that voltage – the charge of being Jimmy – but one way I’ve seen writers deal with the threat of being destroyed by their material is to dial back its intensity. You didn’t, even in Just Above My Head. If anything, that book, far from backing off, brings everything to bear.

I myself have no powers of mediation in what I’m called upon to write. No psycological escape valves or ejector seats. All I can do, when I feel myself getting lightheaded or scarily out-of-the-body is to try to slow slow my breathing down. It’s something I rolled over into my writing practice from studying Ba Gua Zhang.

In your introduction to The Amen Corner, you say“no Frenchman or Frenchwoman could meet me with the speed and fire of some black boys and girls whom I remembered and whom I missed; they did not know enough about me to be able to correct me, [but it] is true that they met me with something else – themselves, in fact – and taught me things I did not know (how to take a deep breath, for example), and corrected me in unexpected and rather painful ways.” [p. xiii.]

And indeed, what’s the hurry? The fountain keeps spraying, the Manetta still flows, its fumes rising up through the drain grate a few inches from my foot, beneath this bench. The summer’s still turning with infinite lassitude to another season.

Would you recognize the rhythms of this place, of your city today? Manhattan, even the Village, is moving to a bourgeois beat. Biking down Seventh Avenue this morning, heading for Sheridan Square, I passed young whites in their multitudes, wearing yoga gear and teeshirts and cargo shorts, seated, lounging, or hovering around what pass for cafés. Manahampton, mon amour, come at last.

August 6

However thronged the park, however torrid the weather, none but the mad, it seems, partake of the fountain’s water these days. What happened?

Well, it’s true, the jets of water have been strengthend – they aren’t as tame as a few years ago. And the central gusher has been augmented by eight subsidiary sprays all arcing from the circumference toward the center. Thus the sightlines down Fifth Avenue, or approaching from Washington Place and along the Allée are stunning – nearly Versailles-like in their extravagance and scale.

The closer I get, the more strongly I feel the fountain’s pull. Nor are there any signs to discourage or forbid bathing. Indeed the potential lies open for every sort of cooling encounter between a placid wade and a rigorous soaking. And the shallows at the edge still make grand splashing ground for toddlers. Am I missing something, some warning, some interdiction, that everybody else can see, or feel?

No hawk today, but rather an ever-nettlesome question which hovers in the air above the fountain: What is one allowed to do?

Or put another way, who permits whom to do what?

Specifically: Is it permissable for a white, straight guy to write about how James Baldwin writes about love? Does his being Jack’s son factor into the calculation?

I’m not expecting you to answer, Jimmy. Instead I’ll take my license from the children of those women and men who you say taught you something about breathing: those kids of my generation, the Soixante-huitards, who scrawled Il est interdit d’intedire on the walls.

But all sorts of things get written on the walls in Paris. Not long before May ’68, right around the time you were in Istanbul were finishing Another Country, some less tolerant sons of the Hexagon painted Ici on noie les Algériens on the Pont Saint-Michel. Such language was descriptive, not metaphorical. We don’t breathe water.

Today, in the Park, one’s feet negotiate a host of pavement chalk circles: Good Luck Spot, Bad Luck Spot, Very Bad Luck Spot, Kissing Spot, Fucking Spot, Free Hugs, and depending on the chalker, Black, Trans, or LGBTQ+ Lives Matter, something about Gaza.

Once upon: before the hanging elm was a seedling, before this was a park or even a parade ground, these acres had the yellow-fever blues. Who’s down there still, lying beside the Manetta’s flow?

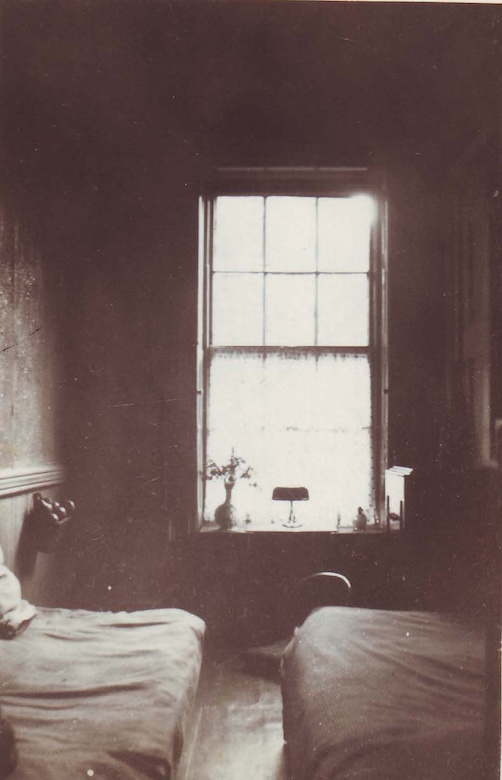

Jack’s room, shared with Jimmy. 58 Washington Place. Circa 1944.

* * *