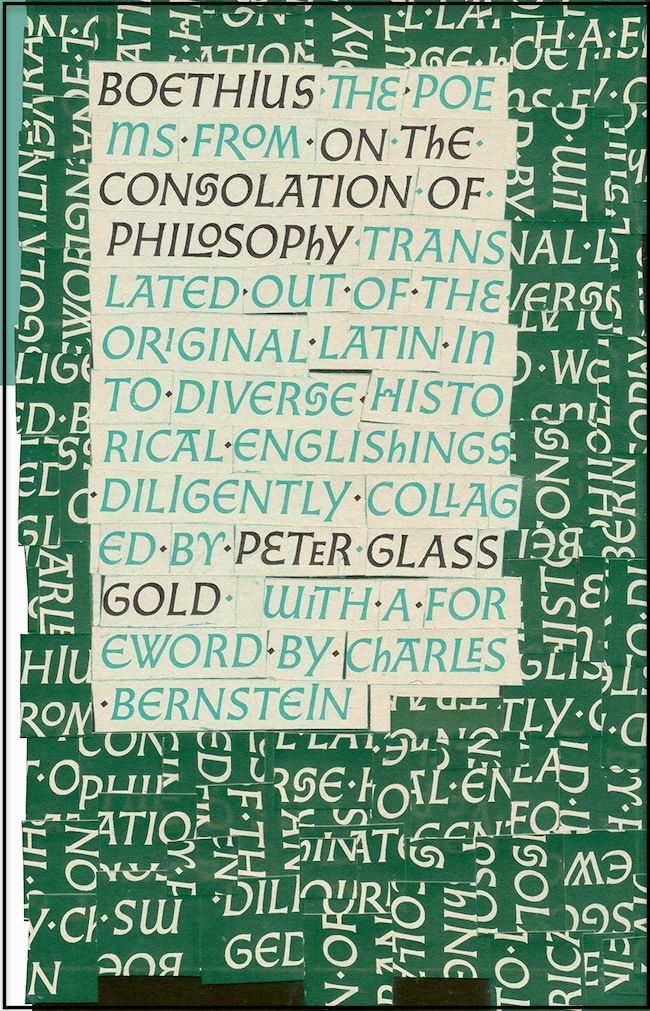

Translated Out of the Original Latin Into Diverse

Historical Englishings Diligently Collaged by Peter Glassgold

With a Foreword by Charles Bernstein

Poets in the Anglosphere know the limits of our modern English vernacular. We marvel at the wallop of Beowulf’s Old English, where alliterative prosody gives us “geong in geardum” rather than the hopelessly suburban “a youth in the yard.” We despair at the lost resonance of Elizabethan-age sonnets, when our own sonnets often seem so paltry. What if we could just pull our English from every age and dialect, selecting the sounds and rhythms that work best for each poem?

That question gets a brilliant answer in the 2024 reissue of Peter Glassgold’s Boethius: The Poems From On the Consolation of Philosophy. Glassgold has crafted a unique translation of the poems in the Latin masterwork of prose combined with verse by Ancius Boethius (c. 480–524). The translation draws sonic elements, syntax, and diction and from the many “Englishings” created since the 9th century. Glassgold set himself the challenge of pulling the English best suited to the poetic task, and succeeded in creating an enchanting volume.

The poems in Boethius’s Consolation are indeed a worthy choice for Glassgold’s endeavor. The work has been loved and translated by writers and regents in Old, Middle, and Elizabethan English, such as Alfred the Great (848–899) , Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1343–1400) , and Queen Elizabeth the First (1533-1603). The author, Boethius, the paradigm of the courageous intellectual, finding solace in philosophy—and writing about it—while in prison and condemned to death. Boethius philosophized when it really mattered; he voiced an oppositional “Numquam!” to the maxim of La Rochefoucauld, “Philosophy easily triumphs over past and future ills; but present ills triumph over philosophy.” Finally, the poems themselves are a wonder of imagery and metaphor, foreshadowing the purposiveness of Dante and the metaphysical conceits of Donne.

In his roguishly eloquent foreword to the book, the poet, critic, and translator Charles Bernstein describes Glassgold’s project as “pataquerical.” The prefix “pata” derives from a French pun for something “beyond what is beyond.” “Patascience” is a parody science of the imaginary; James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake is a book full of “pataforms”—a mix of languages, phonemes, strange diction, and puns that creates meaning beyond the lexicon.* Glassgold’s 1985 collection, Hwæt!, prefigures his Consolation volume as a translation of 20th century poetry into Old English. As Bernstein writes of these works:

Pataquerical works need be neither parodic nor comic; Glassgold’s are neither. While the concept underlying each book may, initially, seem comic, their effect is not: something else happens when you read the works and become immersed in their novel linguistic soundspaces, both familiar and foreign. Both works are part of a tradition of radical, defamiliarizing translation—cousins to homophonic translation, for example, where poems are translated into similar sounds rather than into equivalent lexical meanings.

Glassgold’s translation of Boethius may not be comic, but it is profoundly entertaining. The voices of the two characters in the book, Boethius himself and the goddess Philosophy, are more distinctly rendered in Glassgold’s patagenic collaging than in the modern translation I have on my shelf. For example, in favorite poem of mine, from Book III of the Consolation, the character of Philosophy makes it clear via an extended metaphor that, for all the technical knowledge humans have, they are utter dimwits when it comes to knowing what’s truly good for them—which later in the text turns out to be the path of virtue and piety. A few lines from the poem capture Philosophy’s terse reproach to humans: you farm well, you mine well, you fish well, but you don’t know how to live well; you look to worldly things when you true good comes from heaven.

You seek not gold in a green tree

nor gems pluck off the vine,

ne hydath nan nett on heahmuntum

your dische with fische to fil…

But where lies hid thæs godes hie wilniath

blind thei byden unwar,

and what thurhfareth the sterry heuenes

they seek in buried ground.†

A feature of Glassgold’s book that charmed my ear was the surprising switch and weave between the older and newer words of my native language. The quote above illustrates this. It begins and ends with phrases in modern, or at least Elizabethan English. In between comes the hearty, satisfying cadences of older English. The juxtaposition of sounds and rhythms creates moments of delight. There is a little “aha!” at every alteration, akin to the moment when a baseball pitcher throws a curve after a few fastballs.

Another of the pleasant experiences in reading Glassgold’s book is the growth of one’s mastery of the language. Initial reading of the first few poems compel repeated trips to the book’s thorough and welcome glossary of words not part of contemporary English. But reading on and reading again improves understanding. The process is a lovely reminder that English has a history we carry deep within us, and we intuit meaning from the old sounds once we begin to attune our ears.

Glassgold’s work may be a particularly gratifying experience for those who have studied Boethius in an academic setting. The book breathes fresh life into the poetry of the Consolation. In this translation, poems express the emotional need for philosophy that Boethius felt as he faced execution. Philosophy, for Boethius, was not an exercise in argument or acumen. It was comfort in distress, succor for the soul. It was dignity at the hour of death, shown to us with all the dignity our splendid English language affords.

Click here for our interview with translator Peter Glassgold

*See Pataphor Magazine. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://pataphormagazine.com/meta-%E2%86%92-pata.

† NB: æ = “a” sound, as in “cat.”

* * *