Curlews on Vulture Street, by Darryl Jones

Many years ago, when I was still living in New York City—at this time, to be more precise, in the Bronx—l worked the graveyard shift as a paramedic in a downtown Manhattan clinic and normally came home in the wee hours of the morning. There was a pocket park between my subway stop and home, a 3rd floor apartment, atop an actual house overlooking that same park. In those days, there was a well lit path through the park which was quite safe, the quickest way to home and a much-needed rest.

As I walked wearily through that park one particular homecoming, something stirred ahead. Good Lord, Procyon lotor—a raccoon—going about its raccoon-ish business! Upon seeing me approach it skittered away into some nearby bushes; and the next day I called the Bronx Zoo: “Are you missing someone?” I asked. Politely the person on the other end of the line informed me, “no, Dear, there are wild raccoons in New York City.”

Even then, I remembered remarking upon the deer that venture into our urban spaces.

Some years later, when living in western Massachusetts, I encountered signs along one of the suburban roads warning of salamanders crossing the road; later the township constructed tunnels under those same roads to allow to allow the salamanders to cross from where they “burrow in the winter and the small ponds where they mate and lay eggs in the spring.” (https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/henry-street-salamander-tunnels-amherst, accessed 8/9/24) That included their even more tender young.

Indeed, in our many urban and suburban worlds, “Nature has come to town,” as Aussie urban ecologist, Darryl Jones, comments re: the arrival of curlews on the city streets of Queensland state, Australia—more specifically upon the sight of a lanky curlew herding its tiny young across a main thoroughfare in Brisbane. Remarkably, when Jones notifies the police of their presence, the sargeant at the desk alerts an underling to contact the appropriate agent to put up a sign.

British readers may remember their childhood read, Francis Burnett’s The Secret Garden. much later made into a movie. Estadounidense—US—readers more commonly might recall Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, his 1854 account of living in the woods of Massachusetts. Au contraire, Daryll Jones’ book is factual, both biography and an account of his observations of nature coming to town, as well as his work trying to help urbanites cope with the newcomers. As such it is a provoking read. Dare we say that Thoreau’s observations on Walden Pond are a more romanticized reading of human beings’ relationship—or absence thereof—with nature? We H.sapiens are a keystone species[i]—i.e., we affect the natural world around us and can open it up to flourish rather than what seems to be the case now—to perish. The concept of ourselves as just another mammal, just another species in the natural world, however, does not sit well with the pious:

What is man, that thou art mindful of him? And the son of man, that thou visitest him? For thou hast made him a little lower than the angels, And hast crowned him with glory and honour. (Psalms 8:4-5, KJV)

Not quite animal, not quite divine. Apart. Even those who should know better seem to rankle at the idea that we are but another animal on this planet. Jones does know better and lets us know it, even as he chronicles his childhood love for the woods and, especially, its feathered creatures, as well as his adult discovery of how the non-human natural world has come to our rather peculiar, even sterile, urban one. The list of creatures he encounters, including invaders imported by colonists to make this new continent feel more like the home they left behind, and including such invasive pests as rabbits—the names he lists of Aussie natives sound rather exotic to this writer, but only from lack of experience of them. Jones then settles on the study of an oddball one that diverges from what many naturalists would consider normal avine behavior, the Australian Brush Turkey.

Yes, an odd bird that. The brush turkey male builds a huge mound out of leaf litter and dirt, two to four tons of the stuff, creating a heap that can reach up to four meters wide and one to one and a hlaf meters high.(https://www.qld.gov.au/ environment/plants-animals/animals/living-with/brush-turkeys, accessed 9/9/24) Inside, the temperature slowly rises so that when a female comes along and she and the male mate, she starts digging around and lays her single egg inside the mound, sussing out the precise temperature for the egg to develop and become—la! viola!—a hatchling. The male mates with several females and each will lay their egg in the nest. But then when the hatchlings emerge, sorry, folks, they’re on their own.

So much for the busy little bird outside my window, going back and forth from nest to the wider world carrying food for its young. It’s a cruel world out there in Australia, and a little more than half of all brush turkey hatchlings do not make it to adulthood.

Are these birds at least edible? Though their eggs have sometimes been consumed, as of 1992 and Australia’s Nature Conservation Act, it is illegal to harm brush turkeys. Presumeably “harm” would include making them dinner. Worse, by some people’s estimation, is that some of these enterprising birds, as noted, have left the mangrove and eucalpt forest, and come to town. Regarding these latter, Jones chronicles his encounter with a suburbanite complaining of the mess that, in making a mound, brush turkeys have made of one of her more European-style “borders” (flowerbeds). By informing her of what the bird was doing—its mating, its egg-laying, and so on—Jones actually manages to capture her interest in the bird; and she agrees to let it stay (originally she had wanted to call in someone with a shotgun who would shoot the offender.) Indeed, asserts the Queensland government website: “For brush turkeys to survive in urban areas, people must respect their natural behaviour. With a little planning, brush turkeys and people can happily coexist.”

Jones goes on the chronicle the [mis-]adventures of critters come to town. On both humans’ and birds’ sides adjustment is sometimes fraught: I was shocked to read, among other things, that Australians look askance at feeding wild birds; and for some time, those who did kept this habit of theirs under wraps. Some were even feeding birds “mince”—for our US readers, that’s the Aussie and British slang for ground meat—never minding that their visitors were pollen and nectar eaters. On the avine side, whilst the adults might have indulged in junk foods, they scrupulously still feed their young the traditionally gathered seed (insects and worms in the case of those who traditionally eat them.)

So, is this “nature writing”? The book, and others like it, do not succumb to the more conventional perspective of writer outside peering in at the glories of the natural world as one might a Van Gogh or, say, an intricate medieval manuscript. What I am hinting at is that besides singing the praises of wild landscapes and their denizens, and as H. sapiens continue to expand their cities worldwide, meeting up with wildlife that dare enter—foxes in London, possums and raccoons and other raiders of waste bins, birds previously inhabiting more pristine areas—that nature writing needs accommodate these as well. Consider that, growing scientific studies assert that other creatures darn well have consciousness, that whales and some other creatures actually have specific sounds—names—for each other, that accommodating to pollution and foods with less carotenoids, New York City finches’ colors are duller than their wilder cousins (https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/13/ climate/dirty-birds-color-climate-pollution.html, accessed 17/9/24). And Singapore, in addition to welcoming several families of otters, thrives with wildlife, if we are to believe evolutionary biologist and an entomologist, Phillip Jones.

Some wildness is jaw-dropping—I remember being but a few yards away from a glorious Quetzal when living 6000 feet plus in the mountains of Costa Rica. Some of this is no less fascinating on a more intimate level—not only the irridescent, buzzing colobri (hummingbirds) that come for a brief sip of nectar from the flowers I planted in pots and set on and around my porch, but also the more modest tufted sparrows who came to feed amongst larger crows, grackles and pigeons as I spread birdseed on my tiny patch of lawn. I stealthily tossed some seed behind my back so these smaller creatures could get at it before a larger bird bullied them into flying off and leaving the seed for them.[ii] One afternoon, what appeared to be an agouti or somes ort of Latino weasel,slid through the chain link fencing that formed a barrier between the back porch (serving as a laundry room) and a scrap of underbrush, presumeably hunting for a snack. Startled, when it saw me it slipped back out, never to be seen again. Normally, such creatures live in the forest, and do not venture near human settlements.

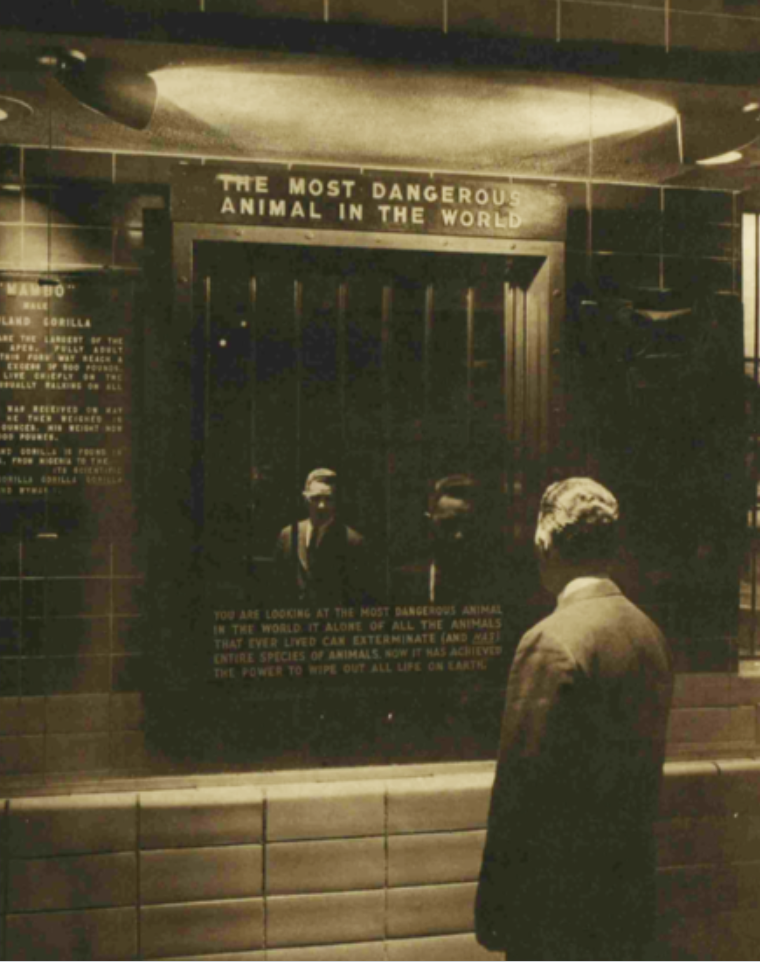

Yes, the myth that we are separate from nature, in my opinion, continues and is a dangerous one; wittingly or unwittingly, some nature writing encourages that perception. All I am suggesting is that as we consider “nature writing,” we might consider that the natural world is not a museum, and its creatures, its flora and fauna are not ipso facto separate: what do we share—or could we share—with the beaver? how have other species adapted to us and we to them? One does not have to, nor should one, anthropomorphise; but, alternatively, the simplistic “nature red in tooth and claw” adage is a Victorian assumption (thank you, Alfred Lord Tennyson) which reinforces separation. Yes, some critters are not to be trifled with; but as the Bronx Zoo once put it so graphically, with a large mirror centrally located as one left the Primate House and accompanying inscription beneath, we are by far “The Most Dangerous Animal in the World.”

— Bronwyn Mills

[i] “A keystone species is one that has a profound effect onthe ecosystem in which they live, especially on theother trophic levels. Keystone species play such a vital role in ecosystems that the entire ecosystem may collapse in their absence. Many, but not all, keystone species are apex predators.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Keystone_species, accessed 16/9/24)

H. sapiens elude that definition only in that we are far too numerous (and far too destructive) for your typical keystone. I first ran into this term as applied to H.sapiens in an aside made by a British zoologist when discussing beavers who copice, not destroy, trees leaving spaces for wildflower meadows to regenerate, slowing floods, etc.

[ii] We take sparrows for granted as common little birds, but some species of sparrow are endangered in the Americas.

N.B. For those readers who have access to BBC UK, an interesting two part series on animals moving in (and out) of the city—“Cities: the New Wild”— can be see at on BBC Two.