May 13, 1948 – February 25, 2024

Famoso Desconocido

by Eric Darton

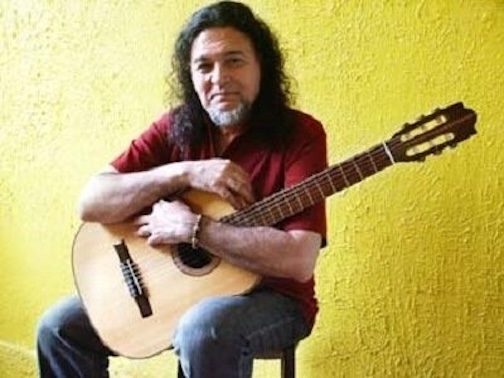

Photo: Cured

It is safe to say that Bernardo Palombo, who I met as an adult, shifted my consciousness in a fundamental way. It is also safe to say that there are scores of people, perhaps hundreds, who feel similarly about his presence in their, our, lives.

One could say that Bernardo was a language teacher, primarily focused on the Spanish of the Americas, and one would be correct. One could say that he was a musician, composer, poet and visual artist, and be entirely accurate. But the ways in which these métiers interrelated within him and emerged into the spaces he occupied produced a synergism that falls nearly beyond description. Particularly when Bernardo seemed at his most abstracted, one felt he was all there.

Many people in the New York area met Bernardo because they wanted to study Spanish in setting that was not a standard language school with a rigid curriculum. So they found themselves walking through the doors of El Taller Latino Americano (The Latin American Workshop). Over the years, beginning in 1979, there were several iterations of those doors in different neighborhoods throughout the city, from the East Village to Manhattan Valley to El Barrio. And though El Taller remains open, thanks to the efforts of Bernardo’s wife Jennifer Pliego and a dedicated staff, and though those doors still gate onto a remarkable cultural nexus, one will no longer find the material Bernardo inside.

But when one entered back in, say, 1985, what did one find? If Bernardo was not immediately visible, he was likely to be somewhere about, soon to emerge. There was something cave and warrenlike, about all of the El Tallers. Yet light was important to Bernardo, natural light, so one might find him raising the shades, or opening a window. There would be the smell of coffee. A counter of some sort with an urn of maté brewing, various teas. Bagels. Cream cheese spread. Fruits. Pastries.

Paintings everywhere, many by Angel, an artist who Bernardo, metaphorically, and somewhat literally adopted. Chairs and sometimes benches around a classroom table invariably covered with a bright, floral-patterned oilcloth. If you came early, as the time for the first class approached, the room would fill up with new students. We would feel – however confident we had been of our intentions until that moment – not quite sure what we were doing there.

Then a tall man – a taller Latino Americano we learned to joke – comes into the room. He sits a the table, picks up and tunes his acoustic guitar and begins to sing. Most of us go blank then, but gradually become aware that we are in the midst of singing “Guantanamera.” Lyric sheets have appeared before us. The song is almost over – here comes the final coro. We have been submerged, utterly, into Spanish.

However unorthodox in its methodology, Bernardo’s teaching was very systematic. Each student received a photocopied set of study guides, hand drawn and effusively illustrated. Bernardo’s focus was on verbs as the driving wheel of communication. In class, he would choose a student and play ping pong with verbs: present, past, conditional. It mattered less whether you understood the meaning of the verb than coming back with an immediate aural response. Then he’d turn the tables and have you ask him questions. If you’ve ever practiced the internal martial arts, think push hands. Sound comes before thought. Just like when you learned your first language. Me gustas tu.

This was Bernardo’s breakthrough: regression, pure and simple. Regression so the new structure would not have to fight with the old one. He should have had a MacArthur.

By the time we finished singing the fifth song, someone would ask: Who wrote that one? And Bernardo would acknowledge that he had, but that his favorite version was by Léon Geico. Or Mercedes Sosa. Or Pete Seeger. Or David Byrne.

Bernardo was not the Beach Boys. But he got around without leaving New York, much less El Taller, very often. He did go up into the Andes with Philip Glass looking for a group of musicians they were hoping would play for the score of Powaqqatsi. Great disappointement when they reached the village – the musicians had left a year before. Where had they gone? The U.S. Two months later, Bernardo found them playing in the Union Square subway station.

Scores of musicians, mainly Latin American but multifarious – jazz, experimental, rock – saw El Taller as their New York destination. SOB was OK, but El Taller was the real deal. Even if there were twenty people in the audience. A few years ago, Bernardo gave a rare, almost solo concert. From get-go, everything went wrong. Guitar strings broke, mics malfunctioned. This was a man who often hid his enormous erudition, which included a nearly encyclopedic knowledge of the English language, behind the persona of an immigrant just off the plane from Mendoza. Halfway through his set, he retuned, shook his head and smiled. “This was supposed to be un concierto,” he said. “But it’s turned into a disconcierto.”

Bernardo had children and grandchildren. He loved food and cooked superbly. At nineteen, he won second place in a national poetry competition judged by Borges, who explained to him that he had won on merit, but that the first prize had to go to an older poet. Bernardo replied “No thank you,” though not as politely.

One could go on forever about Bernardo and hopefully we will. If anyone is ¡Presente! it’s him. His institution survives him, as do, hopefully his methods. His music is encoded in millions of living minds and bodies. Ana Ocarina. Imagen Latina. Cuida El Agua. In El Palomero, he sang of Victor Casiano, a Puerto Rican neighbor and pigeon-keeper, and of Victor’s tribulations in “esta nación fría.”

It’s clear to me now, the mechanism Bernardo used to shift consciousness. Whoever you were, he took you as you were, and asked you a question that you answered differently than you might have done in any other situation. Or he’d give you a book, say, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, or the poems of Nicanor Parra, or he’d play you a tape, like Juan Luis Guerra’s “Ojalá que llueva café,” which invariably triggered some element of the wider, smarter and more inclusive world that had not yet dawned in your awareness, but was nearly there. Like chanticleer, he sensed it, rising. Wherever it lived, Bernardo knew the map of your utopia – by heart. Learning Spanish was the Macguffin. Necessary, but not the point. What was the point? If we knew, we forgot. But our Spanish improved by orders of magnitude.

Once in a while I’d come into El Taller and find the place dark. So I’d call out his name. And from somethere in the depths Bernerdo’s voice would echo. Rengo, rengo, pero vengo.

When Bernardo said something particularly sentient, he’d give it away – attribute it to Foucault, or Buber, or you.

Words and wordplay. His knowledge of connecting links leading to and from the indigenous. If you said “chocolate,” he’d say “you’re speaking Nahuatl.” In Bernardo’s cosmology, nouns dance around an axis mundi of verbs. And he teased. When I misprounounced Soy escritor, he nodded sympathetically and replied: Sí sí, I, too am a shitter.”

So how, in a nutshell, did he change your consciousness? Enough conversations with Bernardo and you’d realize that all your thoughts, your language, and whatever else you imagined belonged exclusively to you, was, as Rabelais put it: “a feast for the whole world.” It’s safe to say, from the perspective of my own seventy-four years, that living is more joyous, more friendly, in Bernardo’s light.

El Taller website: https://tallerlatino.org

El Taller memorium for Bernardo: https://tallerlatino.org/allpalombo

El Taller’s YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/@ElTallerLatino/videos

* * *