by Ian Sasi Mair

Photo: Qian Zheng

I don’t recall having noticed it before in any of the photographs or video images that I had seen of him, but the gap between his incisors was the first thing I saw on the broadly smiling face of Benjamin Obadiah Iqbal Zephaniah. He was over six feet tall, broad-shouldered, and athletic, with dreadlocks cascading down his back below his knees. However, it was the simple beauty of that gap-toothed smile in its full expression, as he greeted me, a stranger, at our first and only meeting, nine years ago in Shanghai, that still remains with me. Gap tooth, in African traditions, is said to indicate beauty, wealth and fertility. Benjamin Zephaniah demonstrated all these qualities abundantly throughout his life.

In his presence, I didn’t feel like I was meeting a poet with the distinction of being included in The Times list of Britain’s top fifty post-war writers in 2008, one who had up to that time received eleven honorary doctorates degrees, among other accolades. Or who had declined to accept the insignia of Order of the British Empire based on his uncompromising anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist principles. I had expressed my admiration and deep respect for him in rejecting the OBE in our previous communication and felt closer to him as a kindred spirit for taking this stance. With just two years separating us in age, and both of us being of Jamaican heritage, I felt as if I was meeting a brother from my Jamaican high school days. The fact that we had both embraced Ras Tafari Spiritual Philosophy, and way of being in the world, further enhanced the immediate connection between us.

I had known about his work and accomplishments for some years. We had previously met in the virtual world of Facebook and gotten to know something about one another through our online communication. The algorithms had somehow brought us into each other’s awareness. Then, too, the likelihood of two Rastafarians living and working in Mainland China, doing what we were doing, are not great, and this generated some excitement about our meeting.

“So happy to meet you here, brother,” he said as we embraced.

“Yes, same here. This is truly magical. Not something I could have expected to experience in China.”

“Me neither,” he responded, with that broad, gap-toothed smile.

Although Benjamin was primarily based in and around Beijing and Henan Province, he agreed to meet me on a visit to Shanghai, which was now less than an hour away from Hangzhou by highspeed rail. This compared to two and a half hours when I first arrived in the country in 2005, ten years earlier. He had already located the vegan restaurant where we would meet as he adhered strictly to that dietary practice. The ambience of the space with its mood lantern lighting, earth tone décor and furnishing, with hints of red, of course, quqing music and subtle aromas, contrasted with my first dining experience in Shanghai, ten years previously. We sat on benches across the table of the booth seating designed restaurant.

Although we had been communicating with each other online, we stumbled a bit over who should start telling his story first. I was more eager to hear about him than to talk about myself. The fact that he was a public figure, didn’t guarantee that I knew everything about him, already.

“First things first,” he said. “Here’s the menu. I’ve eaten here a few times before and the food is just excellent. I can recommend something if you like but check out the menu for yourself. And it’s my treat, so just go for it.” He was not just a vegan, which I am not, but a real foodie, like me.

“My friend is coming to join us, let me call her and see what I should order for her.”

We ordered a mini feast.

“So, tell me, how did you end up on this China run?”

“I was interested in Kung fu from my teenage years – like every schoolboy in Britain.”

“I can relate. It was the same in Jamaica. We grew up on Bruce Lee movies and Green Hornet on television.”

“Yeah, so after 9/11, I couldn’t deal with the hysteria and the madness in England so I decided to come to China first to see the country for myself, and then to train in the martial arts. I made two trips to Shaolin to train with a master there. I wrote a book about that experience.”

“You must have stuck out like a stand of bamboo in a tea field,” I said, tempering my metaphor.

“No, I stuck out like a sore thumb!” he said, getting real. “People followed me around, some watched in fear, others ran away,” he said, gesturing with his huge expressive hands dancing in front of his equally expressive face.

“My experience here has been essentially the same,” I said. “One woman on a bus turned the face of her baby away from looking at me, but for the most part my experience has been overwhelmingly positive. Although my initial attraction to China came from my fascination with the whole different way of seeing the world from what we have grown up with in the west – its speaking, writing, philosophy, medicine and healing, cosmology, I could say that I also came here as a refugee from western society and culture.”

He nodded. “I feel blessed to have the opportunity to come here for several years now, spending three to four months at my home in the countryside outside Beijing. I’ve been teaching writing classes at several colleges as well as studying and practicing Tai Chi and Kung fu.”

“That’s wonderful,” I said, fantasizing about my own possibilities in China, as a Rastaman with certain skills – one who had grown to feel more and more comfortable and at home, here.

“Do you notice any differences between the way that you are respected as a teacher in China, as compared to Britain?” I asked.

“Oh Lord, night and day,” he replied. “Sometimes it’s even embarrassing the way that they fawn over me. And the kindness. You see the respect for teachers is firmly engrained in Chinese culture, and this inspires immediate reciprocity on the part of the teachers.” All of this confirmed my own experience.

“This is deeply engrained in their Confucian ethic,” I added.

Our entrées came: steamed dumplings, tofu, green vegetables, vegan lasagna, seaweed salad, black rice, the aroma of sesame oil with garlic and peppers rising with the steam. We offered a blessing and dived in.

“After all that has been said about China in western media,” I said, “I’m surprised how open the society is. I was cautious at first about even chanting ‘OM’ before my classes, but I took the liberty, and the students chanted with me, and no one came to tell me not to, or shut down the class.”

“Yes, China has been open to foreign religious and spiritual teachings for millenia. Remember Dámó, the Bodhidharma arrived here from India almost two thousand years ago and not only brought Buddhist teachings with him, but also Kung fu. He founded the temple at Shaolin. Their martial arts are grounded in their Taoist and Buddhist spirituality.”

“Yes, yes,” I agreed. “And also Xuanzang, the Chinese monk who trekked all the way to India and back, bringing back with him hundreds of cases of Buddhist scriptures, that he devoted his life to translating.”

China has also absorbed peoples and cultures, including the Manchu who conquered the country and ruled for two hundred and fifty years until the early 20th Century.

As we sat across the table from each other conversing, a certain thought loomed larger in my mind: the significance of our mutual childlessness and how that has affected both of us in shaping our view of the world, and our personalities. For a middle-aged heterosexual man of African Jamaican heritage not to have children is an extreme oddity. We are raised in a Judeo-Christian culture where God commanded us “be fruitful and multiply,” and where “children are a heritage from the Lord, offspring a reward from him and blessed is the man whose quiver is full of them.” We are also from an African culture where a high premium is placed on children, who are regarded as “one’s best investment.” In certain African cultures, a childless man is regarded as still a child. The siring of children is the supreme indication of manhood. I wondered if this commonality helped form an unspoken bond between us, or an energetic vibration.

Benjamin had spoken publicly about this aspect of his life, and he had written one of his most powerful poems revealing the depth of emotion that this aroused within him. I had chosen not to because of the feeling of loss and inadequacy that it brings me. I wondered to myself if his poem, “Naked,” in which he writes: “I need babies to recite to/ I need babies to recite to me/ my life is full of lonely childless eternities/ where only poetry gives me life,” provided any form of catharsis.

Since I have never done any tests, I have never heard the words, “you’re infertile,” from any fertility expert, as Benjamin has. I don’t have the courage to hear that, true as it may be. An article on him in the Guardian states: “He consoles himself with the thought of the hundreds of children who write to him, who come to his readings in schools, who chat to him on the streets of Newham or wait for him outside the Newham Bookshop.

“So that makes up for it – or that’s what I tell myself anyway.”

I tell myself the same about my numerous nieces and nephews who show me this same sort of love and affection, and whose development I have participated in for decades. But it doesn’t add up. Coming to terms with this reality in my life has been one of the major challenges in my yoga practice. Nonattachment (upeksha) is easier said than done.

I had invited this ox into the tea house, so to speak, but I had no intention of verbalizing its presence. If Benjamin had not intuited this in the way that sensitives such as he, might, in discerning the voices of the unspoken, I was not going to raise a topic that all men, regardless of race, class, religion, culture, ethnicity, speak of when they meet: their children. And if I had been deliberating as to whether or not I should broach the topic, all thoughts of that disappeared when his friend arrived. “This is Qian Zheng,” he said. “Zheng, meet my friend, Ian – Yoga master from Jamaica.”

Bespectacled and wearing a formal blue dress, Zheng had the air of a school teacher. I got the immediate impression that she was somehow connected with his teaching duties in China. But the absence of any more precise description of their relationship left my imagination to wander freely.

She sat beside him on the bench across from me, and they chatted about what she had been doing that evening. I listened, intrigued by obvious ease of communication between them and the special relationship that their conversation conveyed.

“Desert,” he suddenly said. “You have to try the deserts here. The most amazing vegan deserts!” I was already so full that I couldn’t take a message but being a man with a dangerous sweet tooth I agreed to indulge. We decided to share a walnut crust raw fruit pie, and vegan peach ice cream. He delighted in the desert like a child. “Isn’t it amazing?”

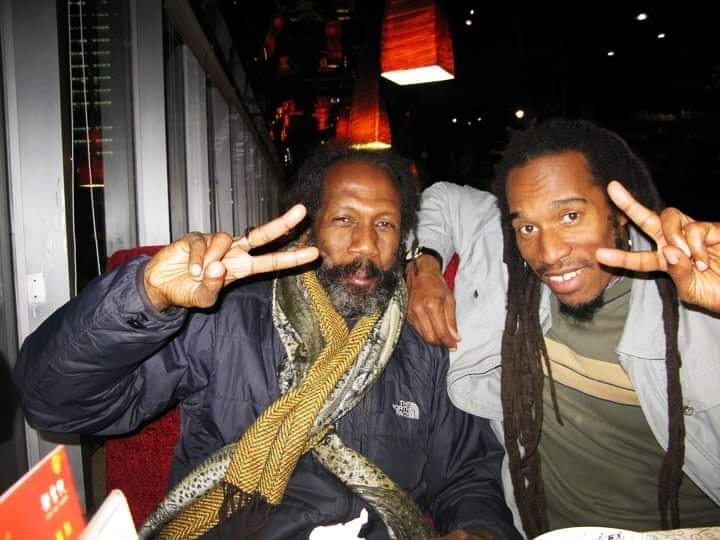

“Zheng, please take a photo of us together,” he said as soon as we finished. He got up from his seat beside her and came around to sit beside me.

“Let’s do this Chinese style,” he said, making the peace sign that Chinese in China like to make when they take photographs with foreigners. He leaned towards me as I held up the peace sign with my right hand, he with his left hand, forming a symmetry.

At the evening’s end, we walked out of the restaurant together, fully satisfied. Benjamin and Zheng waited while I got a cab back to my hotel. Though we had talked of possible future meetings, this was the last time I saw Benjamin. I later learned that he and Zheng were married two years later.

The meeting in China – of two Black men embracing a liberation spiritual philosophy, whose adherents were regarded as outcasts and rebels for long periods of the history of that movement, and viewed with suspicion in the western milieu where we were raised and live – might seem the most unlikely of occurrences. Virtual refugees from a world with a history of nearly five hundred years of Western capitalist slavery, colonialism, imperialism and neo-colonialism, we both found solace and acceptance in a society and culture in many ways strange to us, yet familiar. But it was our mutual belief in the doctrine espoused by Haile Selassie of “world citizenship and the rule of international morality,” as well as our embrace of Non-western ways of spirituality, philosophy and being in the world, that provided the impetus for so rare a moment of connection.

In the past, many Black artists, intellectuals and seekers have sought to escape from western spiritual and intellectual domination. Some left America foor France during the early 20th century, while later, during the post-colonial period, others found refuge in the Soviet communist and socialist countries. What distinguishes Benjamin and my journeys to China from those of previous sojourners is that we two were, at heart, spiritually motivated – totally independent, and free from further European validation or embrace of dogmas. Stepping outside the boundaries prescribed for us, we lived, worked and loved in China as free spirits, exploring possibilities few dare to imagine.

Editors Note: Benjamin Zephaniah (April 1958 – 7 December 2023) was a British writer, dub poet, actor, musician and professor of poetry and creative writing. He was known affectionately as “the people’s laureate.”