Language and Culture: A Brief Introduction

We who are not immediate descendants of the First Americans have been, often quite justly, accused— when not making indigenous lives miserable—of romanticizing indigenous peoples as being more instinctively close to nature, more wise about the natural world and—here we go; let’s just get it over and done with—thus creating the stereotype of the “Noble Savage”. Especially in North America, where attacks on its First Americans have been quite virulent, this stereotype has ironically lingered, as a not-so-helpful antidote to the rumors of President Andrew Jackson’s infamous comment, “the only good Indian is a dead Indian.” The antidote was to assert that in their knowledge of, and lives lived in harmony with, nature, First Americans were, innately imbued with superior goodness and morality.

However, while the conquerors throughout the Americas were highly successful in stamping out Native cultures, some did survive the onslaught. In Mexico, in particular, hundreds of indigenous groups were able to maintain some semblance of their languages and cultures largely because of total disinterest on the part of the government. Indeed, until the Zapatista uprising on January 1, 1994, most had not even heard of the “Noble Savages,” neither the Chol or Zoque peoples who actively participated in the rebellion. And yet their nobility was a fierce force in resisting the government, so noble that after seven years of negotiation, the Zapatista Movement was able to secure for its indigenous people the ability to “determine freely their political status and consequently to pursue their economic, social and cultural development.” The Mexican Government also guaranteed indigenous peoples’ right to participate in the policymaking of their communities, and to conserve their languages, as well as their lands.

This was a major recognition not only that indigenous communities existed but that their rights and regional domains should be constitutionally protected. The law is still in place, but due to the active presence of drug cartels, their way of life is threatened on a new scale. Despite centuries of neglect, massacre, and invasion, these peoples, though in dwindling numbers, retain their land, languages and cultures.

Land is sacred, a home with history, alive, a force, a repository of the magic and wisdom of the ancestors. Among the Zoque and Chol, the continuum between the ancestral regard for nature is present in each footstep of their descendants. And in example after example, indigenous voices lead in telling us about survival in the latter context and of the necessity of protecting that world.

Indeed, are we all not products of nature? Are we not animals, not really distinct as some other creation? Emblematic of this perceived connection in both the Chol and Zoque context, we find a number of references to the “nahual,” the spiritual link between an animal and a human and vice versa: i.e. that creature which is both powerful beast (dare I say protector?) and shaman.

—Bronwyn Mills, with Christopher Sawyer-Lauçanno

How to Be a Good Savage:

Thus, we who still read need to applaud the work of those who are laboring not only to preserve various mother tongues, but to employ them as fully as possible. How to be a Good Savage—a tongue-in-cheek title if there was ever one—is a collection of poems in Zoque, Spanish and, in translation into English. Zoque is an indigenous language spoken largely in the provincia of Chiapas, Mexico. It is unique in not being related to the several Mayan languages spoken there; and in the case of the Zoque spoken by the poet, Mikeas Sanchez (the Copainalá variant of Chiapas Zoque,) that dialect of Zoque is endangered. The book, published by Milkweed in Minneapolis is part of the press’s new Seedbank series; a most noteworthy new response to the above mentioned threats to linguistic and culture, the series brings

ancient, historical and contemporary works from cultures around the world…just as repositories around the world gather seed to ensure biodiversity in the future, Seedbank gathers works…that foster conversation and reflection on the human relationship to place and the natural world—exposing readers to new, endangered, and forgotten ways of seeing the world. https://milkweed.org/seedbank (accessed 4/3/24).

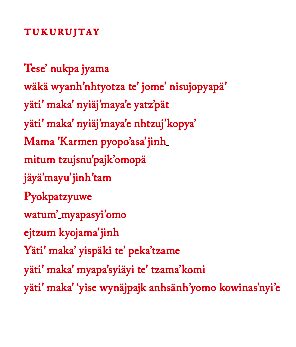

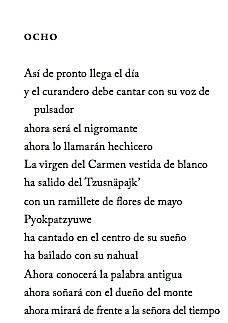

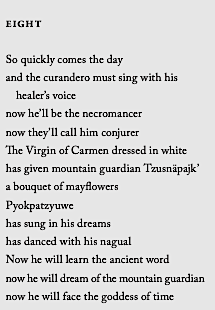

How to Be a Good Savage is a collection of Sanchez’ six earlier collections, the earliest being when she still wrote in Spanish but subsequently began writing in Zoque: she does her own Zoque to Spanish translations, as few such translators exist. Indeed, both in terms of “new, endangered, and forgotten ways of seeing the world” and in terms of safeguarding a language (and, hence, its culture), Sanchez’ collection is a noteworthy example. Like the Chol Maya example, there is certainly a commonality in terms of “forgotten ways of seeing the world.” Importantly, Sanchez also references the nahual, but it is immediately clear that while firmly rooted in indigenous, specifically Zoque, culture and its language, the present Western/Mexican world is not absent. Under the section, WEJPÄJ’KI’UY (NOMBRAR LAS COSAS/TO NAME THINGS) are a series of poems numbered up to TWELVE, which reveal just that:

The above references Sanchez’ abuelo/grandfather who actually was a curandero, and along with one of the more striking things about Sanchez as Zoque poet is her description of herself as an ‘autodidact’. Her grandfather did not instruct her in his practice, but she memorized some of his chants. The tricky part here is that traditionally, a Ore’yomo, or woman of the word in Zoque, is a bit of a conundrum; for women were traditionally excluded from the ways of “wisdom.” When Mikeas entered school, the language of instruction as well as writing, was Spanish, and she first began writing her own work in Spanish as well. Then she taught herself to write in Zoque, whose written form is still evolving.

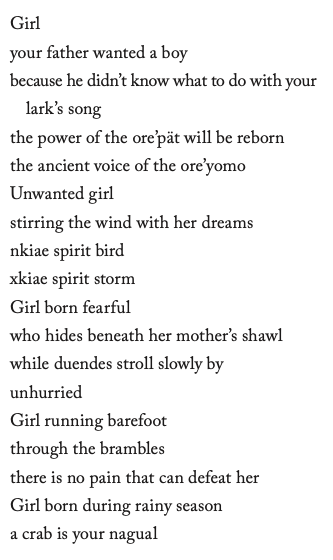

Then, to step off sequence a bit, but stay with theme of the Nagual, consider the first poem with which this book begins:

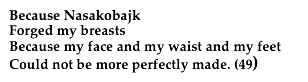

The reader may take the above as a clear statement of the poet’s affirmation of, but divergence from, her culture’s traditional beliefs. I stress that she is not rejecting her culture—were that the case, why use Zoque for her poems? However she does very clearly assert the value of her womanhood: In “Eleven,” (among the 12 earlier poems in the collection) she states, ” I celebrate my sex/and the exquisite shape of my hips/where my lover reclines….” but does not forget her Zoque identity:

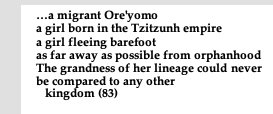

Indeed, though clearly putting the value of women as an important part of her “Zoqueness.” If I can put that so awkwardly, Sanchez treats of other themes. Mind, she had a Ford Foundation grant to study in Barcelona, has traveled outside her traditional world, living in various metropolises, but in those in the collection that have been called her “non-indigenous poems,” her identity is not left out in the cold. Describing Neredya,

The poet cannot leave out the Zoque references: we know she is not sweeping her identity under the carpet, no matter the plight of her subject, “…contemplating her reflection in a Macy’s window.” (Ibid)

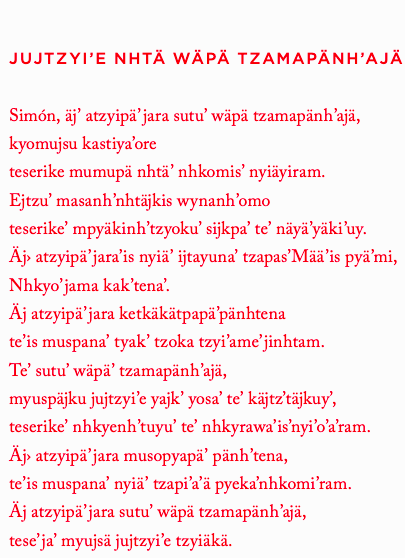

The poet herself has said that “to be an indigenous writer in Mexico is an act of protest, an act of cultural and linguistic resistance, and also a battle against the Mexican education system and against Mexico’s literary elites.” (21) Even further, in this diverse world—not just Mexico—how does one honor one’s indigenousness, not only averting the white person’s “Noble Savage” nonsense, but also the equally patronizing idea of the indigenous person as a museum piece, on display and immobilized in time. (As in that hideous term, “cigar store Indian”). Both of the former risk, in the words of Aimé Cesaire when referring to the plight of enslaved Africans and their descendants: “thingification.” The suggestion, tongue-in-cheek and heavily ironic, that one might strive to be “a Good Savage” by taking on the trappings of the colonizing culture is clearly the farthest thing from the poet’s mind:

To put it another way, one’s home, one’s culture is most assuredly not something that is embalmed, lugged about as a macabre kind of passport. Rather, at least in Zoque terms, the culture is alive and full of riches that should be protected, that should be affirmed as it continues to enrich itself. And, to use my mentor, Ngugi wa Thiong’s’s phrase, the affirmation of indigenous culture particularly by enriching one’s mother tongue is to decolonize the mind, to restore life to, rather than embalm, the language and culture into which one was born. At the same time, so many of us, indigenous or no, live in a diverse world where affirming and enjoying our differences is a worthy cause. Indeed, those among us who wish to diminish, even eradicate this diversity can easily be described as xenophobic, racist, even downright fascist.

In short, the complexity of Mikeas Sanchez’ vision not only speaks to her poetic gifts, her—if I may use the Spanish word, her conscientízacion as a artist of the word and her culture, but the work also details a remarkable journey.

—Bronwyn Mills,

***

Please note that Milkweed, the publisher of this wonderful volume, joins us all in celebrating this month—yes, this April—as National Poetry Month. For every three books of poetry purchased they offer a free fourth. In 2019 the UN declared that year the Year of Indigenous Languages. It offers some interesting links.