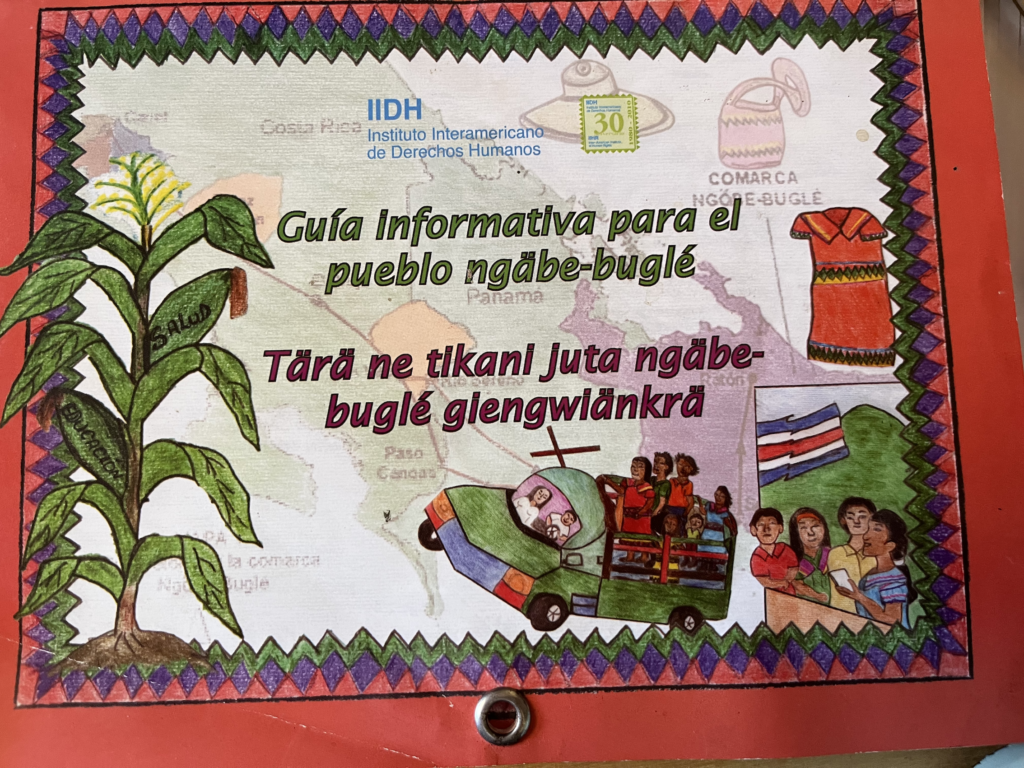

On Feb 27 of this year and en route to considering a book of poetry, written first in the indigenous language, Zoque, and titled ironically How to be a Good Savage, I found a New York Times article, “Mapping New York’s Endangered Languages.” (Mind, New York City has always been touted for its plethora of cultures and languages.) Shortly thereafter I discovered a BBC Radio 4 World Service program, “Bringing Dead Languages Back to Life” about the efforts to retain, salvage and, most importantly, restore aboriginal languages in Australia. I then rediscovered a calendar amongst my things, a calendar in the language of the indigenous people called Ngobe/Ngabe who come from Panama every year to pick coffee in the area where I live. Some have stayed. The Ngobe, who historically never surrendered to the Spanish conquistadores, speak a language which is threatened, according to the ELP (Endangered Languages Project); and here the men speak Spanish now. Though it once was true that hardly any of the Ngobe women used Spanish, from my assiduous eavesdropping, many now do. I hear their language—Guayamí, classified as belonging to the Chibchan family, and going under various names (Ngäbere, Chiriqui, Ngobere, Valiente)—less and less.

All of this is to emphasize what seems to be a renewed interest in the threat of a different kind of extinction: while we humans are, to put it mildly, doing a job on our fellow mammals, other animal and even plant species, languages too are under threat. Language, as my mentors have so often emphasized, equals culture. With the extinction of indigenous languages, goes indigenous culture. Are missionaries still at it? I suppose they are; but the 21st century also brings another, secular curse, not only scarring the minds of our children (and ourselves), but also wiping out the most creative and unique aspects of individual cultures. In the town park, in the little town where I live, I see nearly everyone there in that hunched up pose, glued to handheld screens, ignoring their children, hardly interracting socially any more. In the case of the Ngobe, the language of these handheld horrors is not even their own nor is the debased “culture” thus portrayed that of theirs.

In the above-mentioned New York Times article, yet another of the endangered languages mentioned is Garifuna. The Garifuna people were the descendents of free and enslaved Africans and Carib-Arawak indigenous who rebelled against British slaveholders in St. Vincent and were taken up collectively and dumped along the coasts of Central America, esp. in what is now Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala and Belize. A fascinating language and culture evolved 1 and it is tragic that those who have arrived in New York are losing it, along with that important history. Sadly, it also appears that Spanish and English have nearly overwhelmed the language in Central America.

On the other hand, what more salient illustration of what my old mentor, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, refers to as the ‘colonization of the mind’? A people is conquered, their lands appropriated, their culture, if not downright violently suppressed, is at least damaged by slower, then cumulatively faster, erosion. And so with their language. Think of what is now Canada and the US: the kidnapping/theft of indigenous chidren who were then sent to boarding school and beaten, killed even, when they spoke their own language or otherwise demonstrated evidence of clinging to their own culture. It was not enough to rob indigenous peoples of their territories—colonization—one must brainwash them, too. I.e., their minds must be colonized. (Though they never conceded to the conquistadores, even the Ngobe, driven up into the hills, certainly have had and are having their minds colonized by the most grotesque examples of those conquerors’ ‘culture’.) In a way, the classification of languages as ‘endangered,’ as one describes the planet’s animal and plant species perilously diminishing, that may obscure the cause. In the case of the latter, we obscure the fact that the blame lays squarely at the feet of Homo sapiens and modern humans’ brutal economic systems. In the case of languages, are we not avoiding the causes as well? Colonization, enslavement (the precursor to industrial capitalism2), and, sadly, on and on.

Thus, preserving—not embalming as a static entity—preserving, conserving, enriching a language, especially an indigenous language, is a sacred task.

— Bronwyn Mills

***

- [In Nicaragua] Garifuna are an Afro-indigenous community resulting from the inter-marriage of African maroons (escaped slaves) and indigenous Kalinago (Carib-Arawak) on the Caribbean island of St Vincent. After they were defeated by the British in 1796, they were exiled to the Honduras Bay Islands. Garífuna entered Nicaragua in 1880 from Honduras after having become a highly marginalized community in that country as a result of having sided with the Spanish loyalists in the 1830 war of independence. https://minorityrights.org/communities/garifuna/ *Accessed 4/3/24.) ↩︎

- See Eric Williams’ Capitalism and Slavery (University of North Carolina Press, 1994.) The new, third edition, out April, 2021, was published by Tantor and Blackstone Publishing, and is available both via Amazon UK and US and in an audio version as well. ↩︎