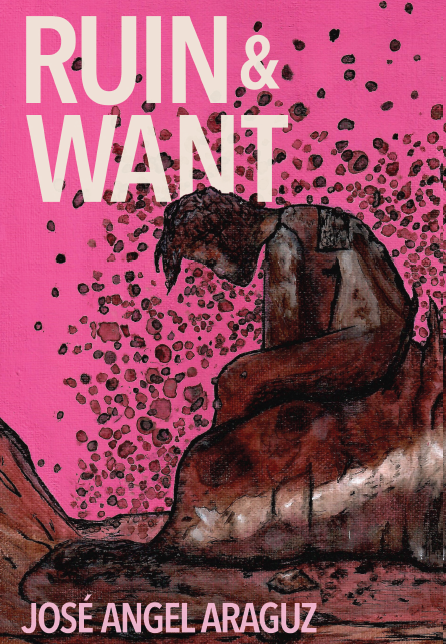

Ruin & Want

by José Angel Araguz

A laceration hurts when exposed. When the shirt sleeve rolls, when the bandage is torn off, the gash throbs, the cut stings. Dermatologic medicine says healing is improved by covering wounds rather than exposing them to air. But one day, long after the scab sloughs, the scar must face the light of day, and the wounded endure a different pain—the pain of living distorted in the world, and admitting what cut you. This is the raw truth of Jose AA’s lyric memoir, Ruin & Want, a devasting book focused on a psychic wound, hidden of necessity for many years, and finally exposed.

I read Ruin & Want in one long sitting, with an urgency I usually don’t feel while reading. The writing drove me onward. Araguz is a poet, and the text of his memoir is prose poetry, with all the power of the lyric voice to compel and captivate. The strong prose serves a stronger purpose. It shows us all how treacherous the road to adulthood can be, and how the damage done on that road is never undone. Araguz has an uncanny ability to motivate empathy: he writes about his own hard climb from youth to maturity, and makes us shudder in recognition. I read the book urgently because, on page after page, I felt both Araguz’s pain and my own

The central experience of Ruin & Want is a sexual relationship between the author and his high school teacher, “L,” in Corpus Christi, Texas. Araguz unpacks every aspect of the affair. He strives to understand what happened, and invites the reader to share in all the discomfort and confusion of that decades-long process. Araguz has the two great gifts of a memoirist: prodigious recollection and prodigious courage. He remembers shame, weakness, and vulnerability. He faces it bravely, and does not shrink from describing it. The adult Araguz now knows that he was used in a “predatory” relationship by a manipulative teacher, “L.” But the teenage Araguz, seeking support after the sexual consummation, shared about it with his teen friends. The result is even greater confusion:

Wanting closure and understanding, I talk about L to others.

Guys pat me on the back and say things like, It must’ve been sweet!…

No one calls it trauma.

No one calls it sexual assault.

No one calls it grooming

No one calls it inappropriate.

The most familiar reaction from anyone is an awkward, heated silence, so much like the one the whole affair leaves me in…

While core of Araguz’s memoir is his exploitation by his teacher, the setting is the poverty and oppression of the author’s Mexican-emigrant family in America’s cruel borderlands. The family’s struggle saturates Ruin & Want. It drenches and colors every part of the book. The strain and disruption in the family makes them both wise and guilty: Araguz’s mother sagely tells him that “anger can poison a heart,” but joins a throng of female relatives who praise his teenage cousin Sylvia, pregnant and “debating whether to go back to high school.” The men in the family commit crimes and watch porn, and Araguz declares that “Like my uncles: when I say I grew up without any positive role models, I mean them and my mother’s exes (of which my father is one, too).

Family dynamics are social dynamics: systemic discrimination, “to keep the Mexicans out of the white side of town” leads to family dysfunction. It also creates the conditions that led a white teacher to take advantage of her young brown student: white entitlement; socially dominant assumptions about gender roles; and Araguz’s fragile self-esteem and his confusion at being a creative, studious child from a family with limited resources. Embedded in every sentence in Ruin & Want is one, unsettling truth: in America: bigotry is the ultimate wound, the deep and weakening injury that predisposes its victims to more hurt and trauma.

An intriguing aspect of Aruguz’s memoir is the set of connections forged between youthful and adult experience. Much of the book’s lyricism—its truly poetic quality—comes from the way it braids these phases of life. The adolescent’s high school affair sours or frustates the adult’s search for love and identity. The adult hates looking back “because I cannot make it all cohere…cannot reconcile anyone’s intentions…cannot move forward without acknowledging the shame…” Growing up, moving away, getting an education all occur in the presence of pain that seems even more intense in the light of new experiences. As Araguz climbs upward toward noble things, the weight of what he carries is even harder to bear.

Araguz has crafted Ruin & Want with care. Both the structure and prose styling of the book drive the reader onward, eager to know the next steps on Araguz’s path from damage toward wholeness. This path is not linear, just as healing is not linear. As book’s seven chapters show, Araguz’s journey forges ahead with insight then backtracks into memory. Sometimes, it comes to a standstill with anguish:

Memory is composed of mites, bedbugs, lice, exes, mosquitoes, words spoken you wish them back, words unspoken you wish them on the air, and other creatures which graze upon the human body indiscriminately. What remains is less than dust and marrowless, yet you fester and heal, fester and heal, and so on, until neglect or indifference keep the soul in place.

This prose poem also displays the technique that powers Ruin & Want. Not one word is wasted. To achieve this, Araguz must choose his diction and syntax with precision. Yet the prose feels natural and unforced. The paradox of meticulous but effortless writing is the sign of Araguz the poet—author of five poetry collections including Rotura, reviewed in Cable Street in 2022 Ruin & Want is a lyrical book in which deftly made prose poems, two pages or less in length, induce the reader’s concentration. I was struck, while reading the book, how rapt was my attention. Ruin & Want is the first book of prose in many years that compelled me to read every word, never skimming, and without so much as a glance at my text messages. The book overcame my iPhone—high praise indeed in our distracted age.

Ruin & Want also produced in me a rare experience many memoirs don’t accomplish. The book dredged up my own “ruin and want” as a result of events and choices in my young life. In other words, this book evoked empathy in the truest sense of the word: I felt Araguz’s pain and desire because his words roused my own pain and desire.

Like Araguz, I wondered about gender roles. From an early age, and I chafed at the constraints of dress and behavior imposed by mainstream culture in the 1960s and 70s, eventually embracing the counterculture of that era. Reading Araguz’s growing recognition of queerness and rejection of normative gender roles brought up my own struggles of years before.

Like Araguz, I came from a working-class family, but found myself with interests in academics and art that my parents and relatives did not understand. I was also naïve, confused, and sometimes ashamed of myself in the presence of people with a family history of formal education and professional work. They knew how to act and talk in these social circles while I did not. I was prone to social error, to faux pas. I was vulnerable to people who would take advantage of my ignorance, such as a group of teachers who invited me to school sanctioned “human relations” sessions, where others were encouraged to insult me because I was louder and expressed myself with Italian gestures.

Not enough has been written about the mental, emotional, and sexual dangers inherent in moving from the working class to an intellectual milieu. With this book, José Angel Araguz has made a tremendous contribution to the literature of class mobility. Ruin & Want releases the long wail elicited by the bruising passage from the working class to the creative class. Everyone who reads will hear the cry, and feel the wounds.

—Review by Dana Delibovi

***