An Interview With Paul Elie

by Dana Delibovi

Paul Elie joined me online from a simple and spare shared workspace in Brooklyn, NY. He sat in front of a cream-colored door with a small silver latch. Affixed to the door was a black foam sound-proofing panel, an essential piece of office-ware given the sirens, backfires, and unwanted music that can puncture a writer’s concentration in New York.

It was late in the afternoon on September 11th. This date, when people turned to faith but also questioned where faith may lead, was a very apt day to discuss Elie’s extensive work on narratives of faith. This work includes the American Pilgrimage Project at the Berkley Center of Georgetown University, where Elie is a senior fellow. It includes his book, The Life You Save May Be Your Own: An American Pilgrimage, which chronicles the intersecting stories of four great Catholic writers of the 20th century: activist Dorothy Day, co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement; Trappist monk Thomas Merton; and authors of fiction Flannery O’Connor and Walker Percy. Elie is also the author of the Reinventing Bach, an intellectual history of music technology, told through a century of Bach recordings. A prolific essayist, Elie publishes frequently in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and other major journals, and has written seminal essays on Flannery O’Connor’s racism and the sexual abuse scandal in the Catholic church. He was an editor at Farrar Straus & Giroux for 18 years.

Our conversation ranged over Elie’s projects, his love of narrative, his Catholic faith, and his approach to writing. We also discussed how the story of a journey of faith can be instructive for any artist, regardless of spiritual or religious beliefs, in the development of both craft and way of life.

DANA DELIBOVI

Tell me about the American Pilgrimage Project. How did it develop?

PAUL ELIE

The American Pilgrimage Project is a university partnership between Georgetown University and StoryCorps, the award-winning, documentary outfit best known for its weekly segments on National Public Radio and its affiliation with the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress. I know David Isay, StoryCorps’ founder, and I’ve kept an eye on his doings for almost 20 years now. In the years after I finished writing my book on the stories of four outstanding Catholic writers, sharing the narratives of their journeys, I was also listening to the stories Dave was assembling through StoryCorps. So narratives, and thinking about narratives, were a big part of my life.

In 2012, when I took the position at Georgetown, Dave Isay and I started brainstorming about a project involving ordinary Americans’ stories of religious belief and how it fits into their lives. We reflected on it together and with others, among them professor of communications James VanOosting of Fordham University. We decided to focus intensely on individual stories. We didn’t want “here are the 10 precepts I believe.” We wanted specific and detailed stories of personal journeys. This became the American Pilgrimage Project.

I think the specificity we sought in the American Pilgrimage Project is very important. For example, when I finished The Life You Save May Be Your Own in 2003, the sexual abuse crisis in the Catholic Church was starting to emerge fully. One read story after story about the failure of the hierarchy to do the right thing, and the horrible stories of sexual abuse visited upon young people by priests. Telling those stories was vital. But I was struck by the repetition in the reporting—the same stories were told in the same way. The specificity and granular detail that I associate with good narrative was missing, and I wanted to change that. So I wrote a long piece for The New Yorker in 2019, trying to address through narrative the sexual abuse crisis involving the priesthood and the hierarchy in the US.

DELIBOVI

In the process you just described, “narrative” is the thread that runs through everything. Why is narrative so important to you in nonfiction about spiritual life, and in nonfiction overall?

ELIE

I have a strong attraction to narrative—a strong sense of the ubiquity and power of narrative. It can be incredibly complex yet communicate directly to people from a wide range of backgrounds and levels of verbal sophistication. I’m just a narrative-oriented person.

One of the most important words in my book, The Life You Save May Be Your Own, is “experience.”

The four writers—Day, Merton, O’Connor, and Percy—brought out the experiential dimension of Catholicism. The narrative of that experience is very powerful. In the American Pilgrimage Project, I wanted people to tell their experience, in the manner they chose to tell it. No interviewer, no script, no bullet points that must be hit. Just turn on the mic and let them talk. Telling in this way seems a beautiful act of fidelity to the experience of the participants.

Those who tell their stories for the project bring forth many feelings. In one case, a Catholic couple who struggled with infertility, miscarriages, and stillbirth spoke of their experience in light of the opposition of the Catholic Church to assisted fertility. It was so painful—we were all crying that day.

A realization that can come from telling our stories is that the story has never truly been told before. My sister and I found this in a session which took place at the Minnesota headquarters of public radio’s On Being, hosted by Krista Tippett—who interviewed me in 2014 and who offered the On Being offices for American Pilgrimage Project story-gathering in St. Paul. My sister and I told each other things we had never said in a concentrated way. We cried, and ended up full of gratitude and surprise.

DELIBOVI

Have you noticed any common elements in narratives of faith, whether from skilled writers like those in your book or from people from other walks of life?

ELIE

First, I should point out a difference between the four writers in my book and the participants in the American Pilgrimage Project.

Day, Merton, Percy, and O’Connor had a distinctly literary and Catholic experience. They looked to predecessors as models for their own religious experience. Thomas Merton took as models the Desert Fathers—Christian ascetics living in deserts of Egypt during the 3rd and 4th centuries CE—and also saw them as precursors of Dorothy Day’s Catholic Worker movement; but Merton found D.T. Suzuki’s path of Zen Buddhism to be a model, as well. This is an established practice in Catholicism, where, for instance, saints are worshipped. The writers walked a path others had walked before, something I call the pattern of pilgrimage.

I found that to be much less true in the stories of the participants in the American Pilgrimage Project. Now, I think we could have induced a pattern of pilgrimage by asking a question like “What story of a predecessor has informed your own faith?” But we didn’t want to do that, for reasons I’ve already explained.

That said, the experiences of the four Catholic writers and the project participants often share this feature: trauma involving religion, with religion as either the problem or the solution. Thomas Merton was an orphan. Young Dorothy Day had an abortion, which she regretted; when she later became pregnant and had a daughter as an unmarried woman, she was grateful to God. One of Walker Percy’s parents committed suicide and the other died in mysterious circumstances. Flannery O’Connor’s father died when she was 15 and she had a mortal illness. It is a valid reading of these authors to say that their religion is in some way compensatory for trauma.

Likewise, in the stories in the American Pilgrimage Project, we find that religion is a site of great sensitivity—of trauma inflicted, trauma dealt with, or trauma leading to a change from one faith to another. When we finish the project, I will have to reflect more systematically on what this might mean.

DELIBOVI

Does this suggest that trauma is what motivates religious practice?

ELIE

It’s true that trauma is often present in journeys of faith. But religion is alive and well in the US, in a way that belies a single focus on trauma. I’m continually surprised by people from different backgrounds and different religious traditions, who make a real commitment to their faith. It’s an important part of their lives, and they are very articulate about it. There’s no worldly gain in it; they are there for the canonical reasons of yearning, a sense of supernatural, and a tie that binds across generations. It’s a counterpoint to the narratives of faith’s decline. I suppose decline may be true in the aggregate, but that’s not what I feel when I meet the people who share in the American Pilgrimage Project.

DELIBOVI

How has the work shaped you as a writer and a person of faith?

ELIE

The language of religious experience has become a language I speak. I’m conversant, not fluent—I’m not Proust or something. I speak that language with a Catholic accent. This feels true for me. And it shifts my sense of what it means to be a Catholic away from worn out formulations like “practicing.”

In my darkest moments, I’m realize I’m going to be reckoning with the Catholic Church for the rest of my life. But I want to reckon with it on the inside, not as an embittered ex-Catholic. My favorite Psalm is Psalm 27—I seek to “dwell in the house of the Lord all the days of my life, to behold the beauty of the Lord, and to inquire in his temple.” I want to be inquiring in the temple, and I want the beauty. I’m there for life.

I know this affects my craft, because it affects me as a teacher of writing. I teach a first-year course at Georgetown in nonfiction narratives involving a personal search. I include books like Barack Obama’s memoir, Dreams from My Father, Hunger of Memory by Richard Rodriguez, Jhumpa Lahiri’s In Other Words, and Dead Man Walking by Sister Helen Prejean. The aspect of writing that I emphasize in most of my courses is something I’ve already touched upon: the use of specific details—”concrete particulars” some call them. My writing is highly detailed. Detail brings vividness. It’s how writing comes alive.

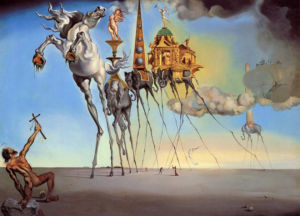

To come full circle, my commitment to concrete particulars is wound up with my sense of Catholicism as a deeply incarnational religion that emphasizes the body of Christ. In Christ, God became human and lived among the people of the ancient Near East. His life was a certain length; then it was gone. He had certain friends and not others. He lived in some towns but never visited others. I’m moved by the intense particularity of the Gospels and the love for detail that infuses Catholic art—whether it’s Baroque altars, Gothic architecture, or Caravaggio’s painting Conversion of St. Paul on the Way to Damascus, where every hair on the horse is rendered. I think of myself as working in a mode that’s sponsored by the religion I belong to.

This isn’t to praise myself or Catholic writers more than those of other traditions. There was a school of thought in the 1960s and ‘70s that stressed a special, sacramental aspect of Catholic writing. That kind of Catholic triumphalism is out of date. All I’m saying is what I know about my own tradition, and how that tradition has emboldened me as a writer of narrative.

DELIBOVI

I want to return to the idea of pilgrimage you mentioned earlier. In The Life Your Save May Be Your Own: An American Pilgrimage, you defined the pilgrim in a way that sounds like a writer. The pilgrim journeys to the sacred site and seeks to be changed. Then, the pilgrim returns and tells the story to others the way a writer does. Do you see yourself in that role? Is it a role other writers share?

ELIE

Yes, I see myself in that role. It’s the structure of my life as a writer. I’ve made a pilgrimage through the lives and works of Day, Merton, O’Connor, and Percy, and I’ve told the story, so that others may enter into that pilgrimage. Plenty of readers have told me that that’s the case. I also aware that a lot of what I know about the four writers might not be known by the next generation, without someone to set it forth.

A question that continually came up after The Life You Save May Be Your Own was published is “Where are the Catholic writers today?” I’m working on a book now that addresses that question, not in terms of Catholic artists per se, but about current writers on margins of religion, who have made work that is distinctly religious in its imagery. I call this “cryptoreligious” art, and it’s not confined to writers. I wrote about Andy Warhol as a cryptoreligious artist in a New Yorker essay published in 2021.

DELIBOVI

Most of Cable Street’s readers are artists themselves—writers, visual artists, musicians, filmmakers, and others. Do you think considering a faith journey, either their own or the journey of others, is instructive in developing story, tone, and imagery in their work. What are your thoughts on this?

ELIE

I don’t want to tell other artists what they ought to do. The most I can do is suggest some things that have been important to me.

One is to reiterate my emphasis on concrete particulars and the value of individual experience. The details of individual religious experience provide a model, applicable to writing about other kinds of experience. An example that comes to mind is Libra by Don DeLillo. His character Nicholas Branch read the entire Warren Report about the assassination of John F. Kennedy—all 26 volumes. DeLillo also read it. He found within it the particular texture of American life circa 1963 and 1964.

Second, the faith journey travels inward, and writers travel inward, too. Thomas Merton said, “our real journey in life is interior.” Inwardness has been a powerful idea for me, for my sense of religion and as a writer. I associate the term with Søren Kierkegaard, whose inwardness as a writer is profound. I would say that in all my writing, I am concerned with capturing the inner lives of the people I write about. This is where we get down to the level of craft in nonfiction and biography. Of course I include public events in my narratives. Say, Walker Percy’s a guest on The Today Show after he wins the National Book Award; Flannery O’Connor sees or hears about the episode and she writes him a letter. But a central part of my craft is to find and chronicle the dramatic, inward moment when an artist is asking “what am I doing here?” and proceeds to create. The moment when, say, Leonard Cohen is in a New York hotel room in front of a cheap plastic keyboard, and wonders “why am I writing this song?” He’s on his knees, he’s throwing drafts out. He stands up, he plays. He gets another verse, and then another, and he ends up with Hallelujah. Such moments are crucial to the narrative in all of my books.

DELIBOVI

Should we, as artists, try to cultivate these inward moments?

ELIE

I wrote two long books while having a full-time job in publishing. I was surrounded by mountains of manuscripts, like the title character in Max Frisch’s Man in the Holocene. While writing the second book, I was also raising a family. This enabled me to recognize the time I was able to give to my own writing as an intensely enjoyable part of the day. I cherish the inward space of writing. I can’t wait to enter that space in the morning. It’s a privilege to be a person who gets to spend large parts of many days engaged in writing. I sense the inward drama every day, as I sit before the page.

DELIBOVI

Do you think there a connection between moments of creativity and spirituality?

ELIE

Definitely. But the way you asked the question suggests that you are talking about a peak experience. That’s legitimate—but only sometimes. Just as meaningful is the sense of ritual in writing or any other art. I make a framework for my book, and that framework helps me to shape the book further. I get to step into the framework every morning, to extend and refine it. My sense of satisfaction in making these shapes are all intensely spiritual to me, as is the satisfaction of publishing the work and conversing about it as we are doing now.

DELIBOVI

There was a time when art and religion were closely allied. Think of the religious patronage of the arts during the Italian Renaissance, or the fact that so much ancient Greek poetry involves the Olympian gods. This isn’t the case now. Do you think that we’ve lost anything as a result?

ELIE

A few answers come to mind. The intersection of art and religion that you describe is far more recognizable in retrospect than at the time when it is happening. James Joyce was considered an apostate during his career; the crypto-Catholic aspect of his work is more widely acknowledged in retrospect. Conversely, Merton was known for books of spiritual guidance, and not thought of as an artist; his poetry only appeared in small journals. Our sense of art and the artist, of religion and who is religious is clearer in hindsight.

What you said about the presence of institutional religious sponsorship of art is true. And yet, the writers in The Life You Save May Be Your Own did not wait for the right support before they began making their work. The American church at that time was a narrow organization bent on hunting down communists. Many of the priests were not especially literate. They focused on building campaigns and basketball courts, and not on the arts. But that didn’t deter Merton, Day, Percy, or O’Connor. They didn’t wait for the church to be an appropriate art-sponsoring organization to do their thing.

![]() There’s a fair amount of energy in the Catholic world now that’s directed to perpetuating a culture in which Catholic arts will flourish. This effort is powerful and well-intended. But the narratives I spent years with remind me of another path to art, without sponsors to legitimate it. As Flannery O’Connor wrote, a writer has no claims to legitimacy “except those he forges for himself inside his own work.”

There’s a fair amount of energy in the Catholic world now that’s directed to perpetuating a culture in which Catholic arts will flourish. This effort is powerful and well-intended. But the narratives I spent years with remind me of another path to art, without sponsors to legitimate it. As Flannery O’Connor wrote, a writer has no claims to legitimacy “except those he forges for himself inside his own work.”

A great example of this is the artist who is discovered late, the one who only by some miracle gets the work done or gets it published. I’m thinking specifically of John Kennedy Toole, who wrote A Confederacy of Dunces. He wrote the novel, then committed suicide. His mother believed in the novel, wouldn’t take no for an answer, and badgered people to read the manuscript. She turned out to be right—really right. Walker Percy, then teaching at Loyola in New Orleans, had the good sense to read it.

Toole’s book, published by Louisiana State University Press, won the Pulitzer in 1981. That’s just one example of how an artist got work made even in difficult circumstances and how the work was published even when the author was no longer alive. And here we are talking and laughing about it—

Beautiful.

* * *