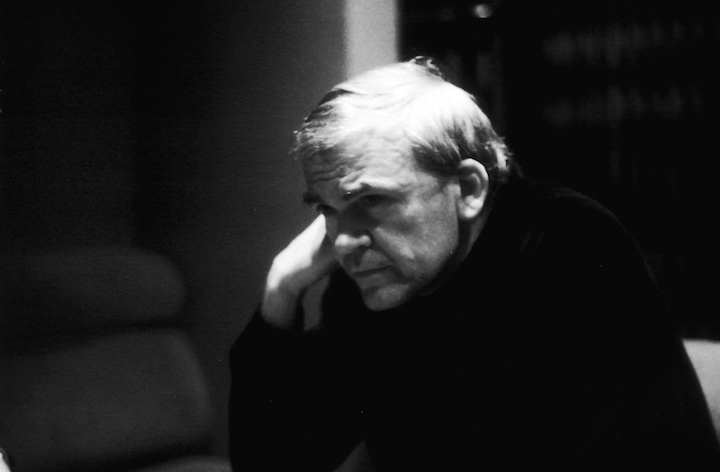

1929 – 2023

In probably 1983 or 1984 I became friendly with Pavel, a research fellow in Architecture at MIT. originally from Czechoslovakia, Pavel was brilliant and funny and politically committed. When I met him, he had been living in West Berlin since escaping his native country in the mid-70s. We used to have lunch regularly at a little diner near the campus. One day at lunch I mentioned that I had just finished reading Milan Kundera’s Book of Laughter and Forgetting and found it remarkable.

Pavel clenched his hands into fists. “Kundera is a fraud,” he said.

“What?” I responded, incredulously.

“Kundera never really suffered in Czechoslovakia. He was connected. Sure, he lost his job, but so did everyone who raised their fists against the government after the Prague Spring. But Kundera quickly realized which way the wind blew and began publicly supporting the government, arguing that it was reforming. And when he decided to leave so he could keep his money, he loaded up his Mercedes and drove across the border as easy as he pleased into Austria. I was in jail for 18 months for opposing the regime; my wife and I had to escape by hiding in the back of a lorry as it crossed into Yugoslavia and then Italy.”

I didn’t know what to say. Just sat in silence for a moment staring at my burger. “He can write,” I finally said.

“But don’t you see? Since he is a fraud, so is his writing,” Pavel stated matter-of-factly.

I suppose we talked more but I can’t recall much of what was said aside from listening to more of Pavel’s accounts of life in Czechoslovakia after the failed Prague Spring. I felt for him and his wife. Felt glad they had made it out safely. I now didn’t know what to think about Kundera.

I read The Joke and Life Is Elsewhere, and then, when it came out in English The Unbearable Lightness of Being. By then Pavel had returned to West Berlin. I confess that I liked the books a great deal, found them at once hilarious and tragic and graced with a unique style. Despite what Pavel had claimed, I also felt they were authentic. I was not so impressed by Immortality or Ignorance but do concede that they still held my attention.I must also note that every time I read Kundera, I returned in my head to my conversation with Pavel. This is not just a conundrum that applied to Kundera but to so many writers. I am enthralled with the work of T.S. Eliot, Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Ezra Pound, all anti-Semites and Fascists. That Hemingway and Philip Roth, among so many white male writers, were misogynists, doesn’t equate with bad writing. Compared to this crew, Kundera manages to stand up pretty well. I salute his accomplishments. One does not have to experience direct oppression to still feel it, and I believe Kundera very much felt it, despite his easy exit. His writing stays with me. Pavel, you were wrong. There is nothing fraudulent about what Kundera wrote.

— Christopher Sawyer-Lauçanno