Editor’s Note

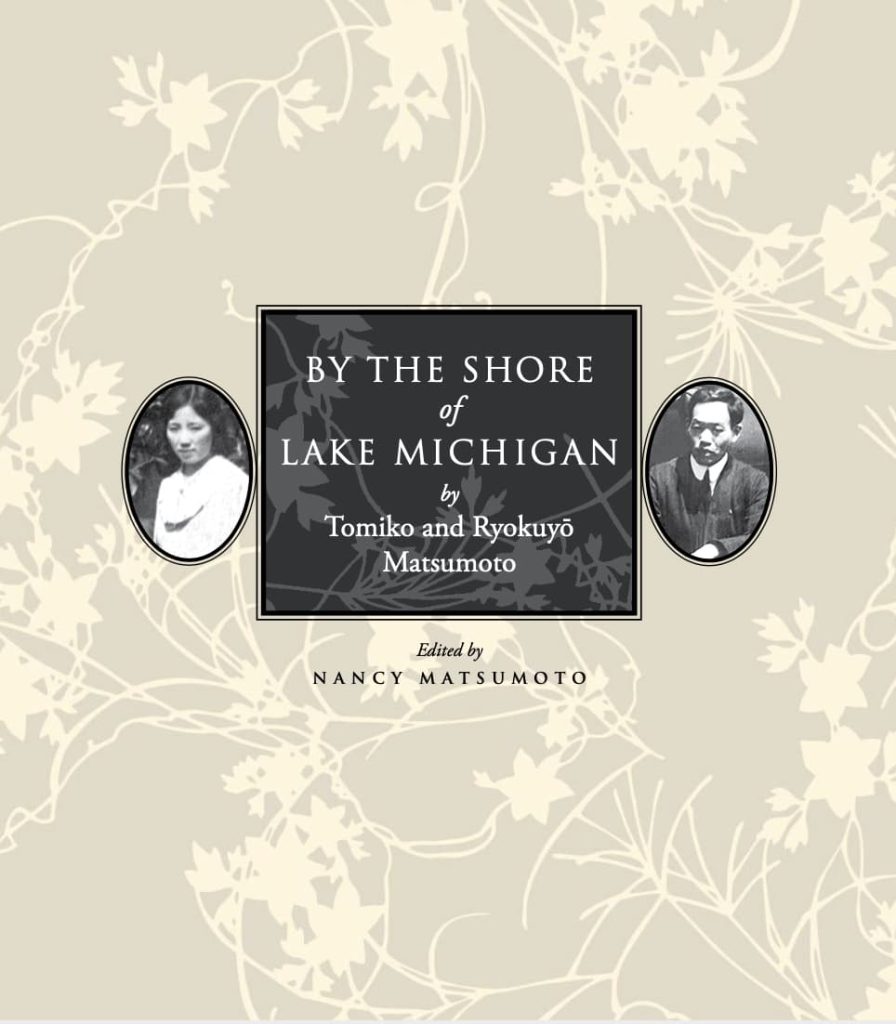

Recently, the English translation of a collection of tanka by Tomiko and Ryokuyō Matsumoto, By the Shore of Lake Michigan, was published by the UCLA Asian American Studies Press and won an American Book Award in 2025. This collection was originally published in 1960 in Japanese, and spans the work of the two poets from when they were in the Heart Moubtain, Wyoming prison camp during World War II through their postwar resettlement in Chicago.

The following is a conversation between the editor of the English translation, Nancy Matsumoto (granddaughter of the authors), and Cable Street editor Hardy Griffin. The collection was translated from Japanese by Mariko Aratani and Kyoko Miyabe.

HG: What inspired you to work on this wonderful collection of your grandparents’ tankas?

NM: There’s a whole story about the World War II incarceration, how that history was really kept from so many people of my generation. I am Sansei, which translates literally to third generation, meaning that my grandparents on both my father’s and mother’s side immigrated from Japan. My parents were both born here, and they grew up speaking Japanese and English, and then their lives were horribly disrupted by the war and by being pulled into prison camps. They went to two different prison camps but had very similar experiences. And so many people in my generation grew up where our parents didn’t talk about it, and if they did talk about it, it was in very vague terms. My aunt would just speak about it like she had the best time with all her high school girlfriends and there were parties and dances, and so I got a very skewed image. There was so much deep anger and shame.

Among my parents’ generation, when they got out, they really wanted to just look forward and not dwell on this very painful chapter of their lives, and so there are people in my generation who still don’t know really what happened. And then there were a lot of people like me, who, as they get older, become more curious.

About 10,000 people were relocated to the Heart Mountain Camp, including my grandparents and my mother and her family. And they just happened to have very illustrious poets there, and my grandmother had always loved writing tanka, and she gravitated to the tanka kai, or tanka club.

My grandmother [Tomiko Matsumoto] and I were very close. I felt that we were sort of kindred souls. As a child, from ages 6 to 9, I lived in Japan. My father worked for the US government, auditing defense contracts through the Vietnam War. And we didn’t live on the naval base, but we went to school there and we lived in a little seaside resort town, and so I had this really kind of cool existence where I learned Japanese. So I could communicate with my grandmother, but because of my relationship with her, I decided after university to spend more time studying Japanese. I started taking university extension classes in Japanese when I was in Boston and then in Los Angeles. Then I moved to Tokyo to work as a journalist for a couple years, and you know, my language skills got better and better. Kyoko, one of the translators is a very dear friend of mine, and she and I started this project.

I really wanted to know what was in this book. I mean, I knew my grandparents were poets, but I tell the story in the introduction of how my mother and the entire Nisei community, the second-generation community, they really didn’t know what their parents were up to, how serious they were as poets. Just the fact that my mother said, oh yeah, they did this vanity book. Then I discovered that, after having a poem selected to be read at the Emperor’s annual poetry ceremony, she was invited to publish a collection of her poems as one volume in a longstanding tanka poetry series.

HG: In your forward, you discuss how both your grandparents loved poetry, but it was really Tomiko who began writing tanka first. And even though Ryokuyō’s poetry was recognized and awarded, it was Tomiko’s work that has received more recognition. What really surprised me was the way the table of contents is laid out, where her poetry across the 17 years of the collection comes first, followed by his—wasn’t that quite different for the time?

NM: She said she had always enjoyed writing poetry. And for her time, she was unusually well educated. Her father was a wealthy merchant, and she used to take a rickshaw many miles to school.

Japanese are highly literate people. To give you an idea, the population of people writing tanka in Japan is estimated to be about 500,000—so half a million people—while the number of people who really love to write haiku is currently six million people.

There are multiple newspapers and magazines that have columns on tanka and haiku, which select from numerous submissions every week, and you’ll notice in By the Shore of Lake Michigan, they talk about a group of my grandmother’s poems being published in installments in the newspaper. They were always submitting, not just to journals in Japan, but also local newspapers in Japanese. And again, their children, the Nisei,had no idea what was going on because they didn’t really read Japanese. They didn’t know the incredible amount of rich literary activity that was going on.

One of the translators, Mariko Aratani, did this whole presentation on why tanka is so embedded in the Japanese soul, and she explains that it’s the rhythm and the combination of five and seven syllables. It sounds really very pleasant and natural and expressive to the Japanese person’s ear, almost as if it was the heartbeat of the Japanese language.

Traditionally, tanka is one long line because Japanese people can hear the breaks in the meter because of the 5-7-5-7-7 pattern of syllables. When you’re translating a Japanese tanka poem, there’s just no way that you can stick to the syllabic structure in English. No one even tries. A compromise has been to render the poem in five lines so that you kind of hear the rhythm, even though the syllabic structure is going to be much more loose.

Reading my grandmother’s poems in Japanese, you can really get some of the beauty of the sounds she’s putting together. It’s just very beautiful and very gentle.

HG: But she packs an emotional punch, even though the Heart Mountain Bungei, a Japanese language literary magazine of poetry and essays, requested that all poetry “exclude mention of current affairs.” I love one of her early tanka:

Is it secretly watching

over ten thousand people

sound asleep?

The moon above Heart Mountain

shines clearly tonight

Do you think that, by not stating the situation outright, but putting the ten thousand people in the camp in this very clear, black-and-white light, the terrible injustice of the US government’s actions is even clearer?

NM: Yes, her poems are very subtle. It’s hard to detect sometimes, but I love the way she’s pulling back the lens to view these 10,000 people from on high. It makes us think of all the emotions prisoners must be feeling in this prison camp.

HG: Your grandfather is also a strong poet, and he’s very humble in his Afterword to the book, in which he clearly shines the spotlight on Tomiko’s work—that also struck me as unusual for that era in Japan or the US.

NM: She is the one who was invited to put this anthology together in the first place, and he says in the Afterword that he was so bold in asking if there might be a place for his poetry as well. It’s interesting because he belonged to a school or a tanka society that was known for being very realistic, and she belonged to a poetry society which was much more about emotions and feelings.

In one poem, she writes how she was drawn to that school. She felt that it was the right school for her. Most of the people involved in the project agree that Tomiko’s are the stronger poems, but what’s so eye-catching about his poems is the way you can see and hear what a patriot he was and how absolutely torn apart he was to be living in America and to be worried about his countrymen starving after the end of the World War II.

HG: Yes. One of his following the end of the war comes to mind:

In the end

not having anywhere

to put my feelings,

suddenly I stand

and let tears fall

NM: You can see how he was just feeling so devastated while everyone else was cheering. Yes, those are really powerful.

My uncle on my father’s side wrote a 600-page memoir called Closure for a No-No Boy. These were men who would not sign an oath of loyalty to the US…

HG: How crazy is that—the US government illegally incarcerating 120,000 people and then asking them to sign a loyalty oath…

NM: Exactly. And in the memoir, my uncle wrote about living with the stigma of being a No-No boy, something that for several decades after the war was looked upon critically by the majority of Japanese Americans. For my uncle, being sent to a much harsher camp, where all of the so-called “disloyals” were sent, was very depressing for him. They were very pro-Japan, constantly doing military exercises because they all felt they were going to go back to Japan. It was a very difficult period for my father and his two brothers as they were the three of the family who were segregated over this loyalty issue.

HG: In her poems from after the war, I found it fascinating that Tomiko comes across as more sympathetic to the US, such as in the tanka:

The zeal

of postwar reconstruction

is admirable—

the way my countrywomen

all fervently work together

NM: That’s an interesting poem. I believe she was speaking of the post-war reconstruction effort in Japan, and admiring the energy with which her “countrywomen,” Japanese women in Japan, were throwing themselves into the reconstruction effort.

There’s another one, though, where she says:

They say

there is still no one else of Japanese descent

yet at this workplace—

I feel

slightly scared

So, I think that is also reflective of her point of view, identifying as a representative of her people and having to show how we’re standing strong and are hard-working.

HG: And then there is a delight that comes through her poetry in describing Black people in Chicago at this time:

With ancestors

in Africa,

dark-skinned people

live dashingly

in America

NM: The relationship with African Americans is fascinating, because of course they were all people who were discriminated against, although maybe not equally. There’s been a lot written about being Japanese American, African American, and Jewish in Chicago at this time, because all of them were victims of redlining. They were all pushed into the same ghettos, and so they were always sort of like in the bad neighborhoods, you know, and they actually had to keep moving, to the South Side as the city was evolving.

So, there’s on the one hand, I think, a sense of solidarity, but then there were difficulties as well.

My grandparents in some ways were very typical of their time, and there are so many tanka in which they really appreciate the naturalness, the humor, the generosity of African American people.

HG: I was affected, time and again, by how open-minded they are. I’d like to ask you about the tanka with the title of the collection:

As I stand

by the shore of Lake Michigan,

the morning sky deepens

stretching on, far away,

to my mother country.

I was transported there, to the shore of Lake Michigan in Chicago, imagining myself there at dawn. The sun would be coming from the East, but Japan is actually in the other direction, away from the lake, in the direction of the ‘deepening sky.’ What do you make of that?

NM: That’s a really interesting observation and reading. The other thing that, I think, is noteworthy—because it’s in the anthology—is there’s a poem about the opening of the Saint Lawrence Seaway, and when it comes, literally the Great Lakes were connected to the ocean, so you know you could imagine these waters are going all around the world, touching Japan. So maybe the opening of the seaways was very symbolic to them, just imagining that these waters were connecting the oceans, connecting to the Pacific.

HG: At the very beginning of the forward, you open with this beautiful description of their study: “My grandparents shared a small corner study in their home in Rosemead, California, where they wrote tanka poetry. The room was painted a cheerful pink, with two wooden desks—one for each of them—placed before its two windows.“

Can you say a little bit more about this room?

NM: Yes, it was very beautiful. When my grandmother talks about just the joy of looking up words in that dictionary. Being engaged in this kind of solitary work, but they were doing it together, writing poetry together. There’s so much happiness. That room always had that feeling. There was a time when I lived with my grandmother for a while, and I stayed in that room.

And I remember seeing all of these tanka trophies. I realized that my grandmother got a lot of awards and accolades for poetry. Putting that memory together with the poems where they just talk about the daily practice. It kind of all came together for me in that room, which was the embodiment of it all. And it was just very cheerful, very sunny. Yeah, it’s a great little room.

Nancy Matsumoto is the editor for the English translation of By the Shore of Lake Michigan. Her newest book, Reaping What She Sows: How women are rebuilding our broken food system, launched in October 2025.

* * *