Jane Goodall

April 3, 1934 – October 1, 2025

Requiescat en Pacem

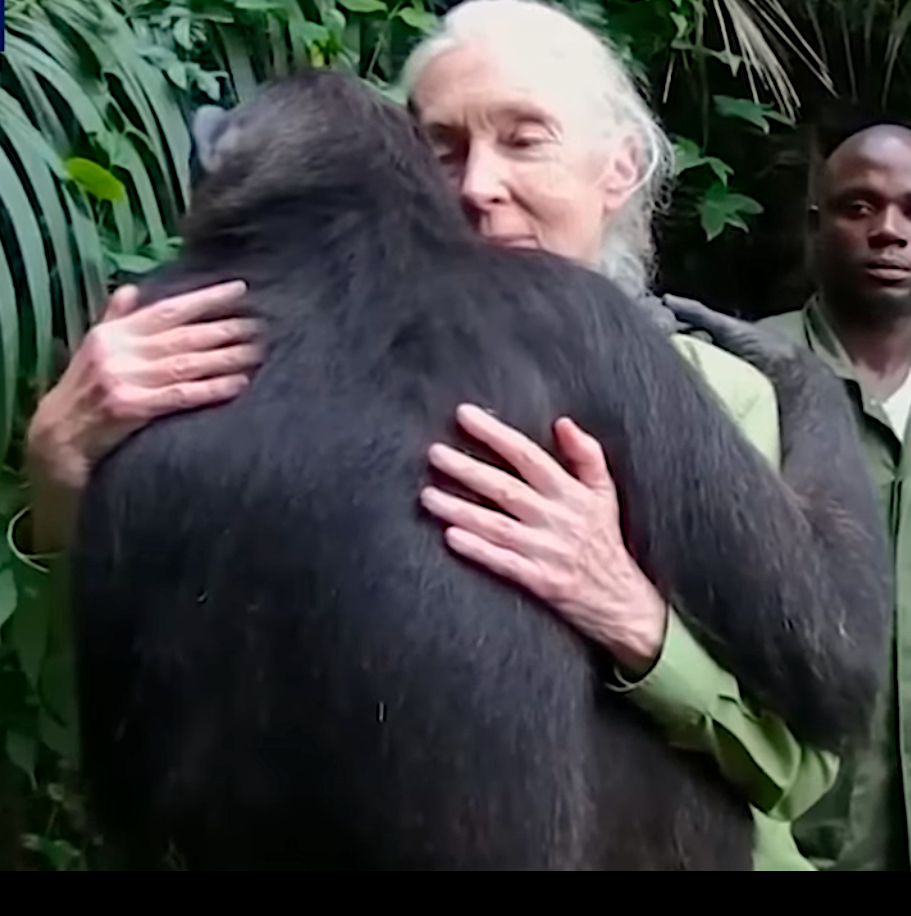

Amongst the flurry of obituaries, in memoriae, and the other many tributes to Jane Goodall, the ethologist, friend of primates and student of same in situ, my favorite photograph is of a simple hug exchanged between her and one of the chimpanzees at Gombé National Park in Tanzania, where she conducted her behavioral research into our closest primate cousins, the chimpanzees.

Valerie Jane Morris Goodall (3 April 1934 – 1 October 2025) was born in London, and for more than sixty years conducted field work largely in Africa, in Tanzania in what is now Gombe National Park. Her father, Mortimer Morris-Goodall, was heir to money from the family business of playing card manufacture and between the two World Wars, of all things, a top driver for the Aston Martin racing team. Her mother, Margaret Myfanwe Joseph, is credited with being a novelist who wrote several books under the name Vanne Morris-Goodall, though the only titles I could find (even listed by the almighty Google) are on non-fiction subjects such as evolution, the rainforest, leading one to believe that there was some confusion between biographer and internet. Jane’s parents divorced in 1950 after the end of WWII while her father was still in the military; and Jane grew up in an all female household (her mother and two unmarried aunts). Jane rightly credits her mother with giving her encouragement, essentially telling the young girl that she could do anything if she put her mind to it; and this was a girl who childishly dreamed of becoming Tarzan so that she could be among animals without discomfort and without them being discomfited by her presence. Early on she began enthusiastically studying animals; she made friends with the birds that came to her window and studied small mammals.

Then, as a young woman of 23, Jane received a letter:

…from an old school friend whose father, in postwar colonial Kenya, had acquired a farm in the hills outside Nairobi. The letter invited her to visit Africa and stay at the farm. (The Guardian, 10/1/25)

Goodall waitressed until she had saved enough money to book a one-way passage to Nairobi, where she stayed on that farm for about a month, and then introduced herself to the eminent paleoanthropologist, Louis Leakey. She became his secretary there, at the Coryndon Natural History Museum. Leakey’s ideas about the evolution of H. sapiens in Africa were new at that time (the 1950s) and our primate relatives were of great scientific interest, though regarded as dangerous and unpredictable as subjects to study.[1] Indeed, soon after Goodall’s arrival, Leakey organized an expedition to a remote part of Africa where wild chimpanzees flourished and where he thought he might get some ideas about the evolution of early hominids. Improbably, he got Goodall, who had no scientific training, to go. To paraphrase, “An Inside Look,” a documentary made by the National Geographic Society [2]—which I urge readers to watch after reading this—perhaps in part because the scientific community did not entirely welcome Leakey’s ideas at that time, he looked for someone whose ideas were not ‘biassed’ by scientific theory. What he was looking for was keen observation and, as noted, an unbiassed observation. Further, reflecting a more gynephobic time perhaps, the British colonial government had ruled that no woman could go into the forest alone [3], and so Goodall arranged for her mother come and join her. It was a fortuitous choice: Jane’s mother set up a clinic for those in that rather out of the way area, one much appreciated by that community and certainly a factor in gaining that community’s support for her daughter’s work

Elsewhere we also read that Goodall, once at Gombe, set out from their camp, armed herself with a pair of binoculars, a notebook, a blanket, no tent, and she sat out as near as she could to the chimpanzees’ community ‘turf”—watching, waiting, often sleeping at the spot. There in Gombe Goodall discovered that chimps used tools (first, a long piece of grass poked into a hole to draw out termites which the animal then ate) and that they ate meat. Gradually she was able to make, for lack of a better term, friends with the animals; and her repeated and careful observations and documentation in the early 1960s at Gombe also established her reputation in primatology. Further, unlike the prevailing assumptions of the time that chimpanzees were mere brutish animals operating solely on the basis of instinct, she

…came to describe the ones she was studying as deliberative creatures who remembered the past, anticipated the future, planned, had emotional lives and were driven by individual personality and character. (“Dame Jane Goodall obituary,” The Guardian, accessed 19/10/25)

Hence the ‘friendship.’ She is also credited with identifying other similarities with our species: passing down knowledge to the next generation and behaviors that included the violent side of our shared primate nature, in what can only be called a xenophobic reactions to other communities of our same species.[4] Indeed, the above photograph does evoke speculation about the common evolution of emotions and relationships amongst one another, and also of our common membership in—of our both clearly being part of, as opposed to separate from—nature.

Though Goodall’s careful curiosity and skill allowed her to make landmark discoveries, she had no undergraduate degree. Yet in 1962, without that degree and given her accomplishments thus far, she was able to enter Cambridge University as a doctoral candidate in ethology, the science of animal behavior. Though specifying objectivity, ethology is not a science apart from the world in which the subjects of that study live—one must observe those subjects in their natural environment. Hence, this was a field that fit in with what Goodall had already been doing, and required the skills she had and continued to refine. She gained her PhD in 1966, as well as becoming a part of a growing trend—more and more women in the sciences.[5]

Goodall returned often to Gombe for the next 25 years, as a world expert on wild chimpanzees. She was clearly a woman of intellectual rigor and, at the same time, open to genuine discovery without cramming those observations into a narrow preconceived theory or doctrine. Indeed, years ago, I remember reading with interest about Leakey’s ideas, and then about her research into chimpanzees. As we and the chimps shared a common ancestor 4.5 to 5 million years ago, or 6 to 13 million, depending upon whether that common ancestor is the Ardipithecus ramidus,[6] or the more recently discovered Nyanzipithecus alesi [7], all this pointed to and affirmed her work as part of the exploration of our shared mammalian past.

Though she had already attracted attention through several articles published in the National Geographic, in 1971 Goodall published In the Shadow of Man, largely about her earlier Gombe experiences and one which continues to inspire readers to this day. Included in a number of others, two key works are most remembered, Through a Window: My Thirty Years with the Chimps of Gombe (2010) and The Book of Hope A Survival Guide for Trying Times (2021). Much of her work was photographed and filmed by her first husband, the wildlife photographer, Hugo van Lawick[8], with whom she had a son name Hugo, fondly nicknamed “Grub.” Notably at Gombe when Grub was a young toddler and his parents were out in the field, he was kept in a cage—really a large playroom with cage-like protection all around—to keep him safe from enthusiastic, curious but rough chimpanzees.

Certainly Goodall never stood still nor “retired”; though in her later years, she left “active scientific research and moved on to a second career as a conservationist and activist”(ibid) where she actively campaigned on behalf of causes favoring the care of our environment and the creatures in it, as well as concerns regarding climate change. When at Gombe, she had not only taken on students, but also formed the Gombe Stream Research Centre, and even after taking on that “second career” she kept the research going there. The Centre is the longest continuously running scientific field station—that and The Jane Goodall Institute, which she founded in 1977, continue to this day (see the recent Earth Medal award created by the Institute). Thus, when turning to thoughts about the natural world of our nearest relatives, one always knew Goodall was there, one of the pillars of research in the field. We now know more about other creatures with whom we share this planet, thanks to her expanded views and methods of investigation. That she is now absent does feel as though the edifice which supported—and supports— those investigations and subjects she brought to our attention has lurched, if ever so slightly.

There was, after all, only one Jane Goodall.

– Bronwyn Mills

1 We share an estimated 98.8 to 99% of our genes with chimps.

2 An Inside Look (2014), accessed 22/10/25.

3 Though there is some suggestion that a female human observer is regarded with less suspicion and hostility than a male H. sapiens observer would be.

4 From the YouTube film, Beauty and the Beasts, made in 2010, about Jane Goodall and her work in Gombe.

5 See The Guardian‘s Goodall obituary, accessed 18/10/25.

6 Ardipithecus ramidus—largely exploring the idea of bipedalism.

7 See The Scientific American, August 10, 2017. Not always found in what are, today, more tropical climes. These links are, of course, subject to what is next unearthed...

8 They divorced in 1974, though remaining friends. Goodall had a seond marriage, as the Guardian obiturary notes “…in 1975, to the British-born Tanzanian farmer and politician Derek Bryceson, ended with his death in 1980. She is survived by her son, three grandchildren and her sister.” (ibid)