Editor’s Note

Eliza and I have circled around each other in various friend groups for many years, even decades. A short list of our mutual friends: Marta, music DJ, theater, art lover; Laura, wild woman who did 15 years in Federal Penitentiary; Chuck, actor who played my husband in the short video I shot in 2003; and Tony and Gail Elizabeth Williams, two artists who were featured in the last issue of Cable Street. Yet, it was only when I did this interview with her that I learned how to pronounce her last name, Gagnon—rhymes with canyon.

Through all these connections and interactions, I was aware of Eliza’s interest in politics, arts, film, even, when we talked about African dance, her drumming, but only when I saw her recent film Island End did a truer portrait of her emerge. That film starts with a place and assembles all Eliza knows and learns about that place: present, past, geography, politics, and economics. By doing so she assembles herself as well—apologies for this theft from Anna Cypra Olive, whose memoir is titled, Assembling My Father.

The trailer for Island End begins: “They say that if you pull on a string, you’ll always find something at the other end. So, it almost doesn’t matter where you start.” This first section of Island End starts with shrubs and becomes a philosophical, poetic revery, “Make a place out of no place / Or no place out of a place.” In the following four sections she takes us on a whirlwind tour of that place/no place, through time in fragments via maps, histories, personal stories, and changes due to how geography morphs over time and how finances interfere with all of it.

On her website, “always in process” she has, besides her home page, six tabs: Film/Video, Drawing, Money, About Me, Diary etc, and Other. Each offers menus with intriguing, multi-flavored works. Under Money, she has videos of her alternate character Sunny, who talks about money and its influence on our lives. The Diary starts in 1971, when she was eight, then jumps to 2017. This diary is first, of course, in writing, but 2017 is video. Her drawings are delicate with a distinct charm. And her About Me delivers a series of head shots from grade school to well-into-adulthood, with overlay of text regarding where she is (place), her driving abilities, and the global and national financial market changes.

On February 23, 2025, I recorded a conversation with Eliza about her artistic life. After the transcription was done, we cleaned it up and Eliza added a few new paragraphs.

Jan Schmidt

Eliza Gagnon interviewed by Jan Schmidt

Schmidt

To start, much of what you do revolves around place. Where did you grow up? How did you grow up?

Gagnon

I was born in Boston and grew up in the South End from the mid-late ‘60’s to the early ‘70’s. And then in Cambridge, across the river, for the rest of the ‘70s, which was a great place to be. I think it’s fair to say that our family situation was often tense, kind of explosive. So I was always interested in things that were going on outside. I wanted to be outside. And there was a lot going on there back then. The South End was a mix of longtime residents, new people, different communities, black, white, Spanish, gay, gentrifying brownstones, rooming houses, regular old apartments, projects, some communes, bookie joints, liquor stores, day labor places, clubs. I would see people hanging out on stoops and I would want to be on the stoop too. I would see people playing bongos, so I wanted to play bongos. There were older kids running wild up and down the alleys and I wanted to do that. And I would see the FBI Most Wanted posters at the post office, and that seemed exciting. To have your picture on a poster.

Also where we lived wasn’t that far from the Combat Zone, as it was called, adult entertainment district or whatever. And there was a Playboy Club nearby. We would pass certain clubs or there would be women coming home from work with thigh-high boots and big hair and stuff like that. I was fascinated and I thought they were so beautiful. One time I asked my father, “Who is she?”

And he said, “Well, she’s a go-go dancer.”

And I was like, “I’m going to be a go-go dancer.”

So that was some of my earliest looking out at the world. My two earliest ambitions were influenced by what I saw in the South End or going from the South End to wherever we were going.

Schmidt

You wanted to be a go-go dancer or on a “wanted” poster?

Gagnon

Or play bongos or something like that. I had a bit of grandiosity, I guess, always. Or fantasy. And I was nerdy too. I could get lost in books. Stacks of books. I had no talent for drawing or painting at all, and I always envied people who did. And I hated writing, but I think I was attracted to humor.

What I did from an early age that maybe became relevant to art stuff later was to make up little plays and skits. With my brothers or friends or my cousins, we’d make up silly plays and have our parents watch them. They tended to be kind of gimmicky, very focused on props, or scatological. Some of them were inspired by Batman, TV Batman. We loved that.

Like I said my house could be pretty tense and explosive, and it was sort of my job to make people laugh, to break the tension. I was a pretty good mimic and I got positive attention for imitating people, like on TV. Henry Kissinger or whoever. It would make my mother laugh. And in school I was kind of a class clown. I would hide behind comedy and silly voices. I remember this time when my grandmother was in the hospital, she was dying, and my brother was going to go see her, probably for the last time. They were going out the door, and my mother stopped and said, “Hey, why don’t you come along for comic relief.” So, you know, I was kind of comic relief. I liked joke books and skits and plays and that kind of thing.

Also, I was caught up in the iconography of the time and what I saw in Life magazine and on the news and your generation and what you guys were doing.

Schmidt

What year were you born?

Gagnon

1963. I think was pretty aware of a lot of what was happening, of the war going on, the King assassination. I think I absorbed a lot from that time that was influential later on.

Schmidt

And then in high school, did you do plays?

Gagnon

I did do plays . . . but can I jump forward for a minute and just say that my bongo dream did come true? Finally, just last year, fifty-something—cough-cough—years later. Through a series of serendipities, I was invited to play bongos with this band. I didn’t know how to play bongos and I’d never played with a band before so I was really nervous. Totally scared. I mean, I’ve been surreptitiously playing drums for a long time on and off so I had some background, but I couldn’t find anyone to teach me bongos. So, I studied diligently with Professor YouTube and came up with some riffs for these different songs. And we performed—and it was great. Also, I had just finished making my film Island End which had taken forever and was really a grind, so I was euphoric. Totally fulfilled. Like I didn’t need to do another thing in life, but sit in the sun and drink coffee and chat. That did wear off eventually.

But getting back to your question, I did do plays—grade school, high school, college—but I was definitely not the star of the show or the belle of the ball or anything. I played music and I did some theatre and dance, and a lot of photography, but I was kind of closed in at the same time. I had a lot of not particularly high self-esteem. And there were substances. But, you know, I had a lot of friends and school was very easy for me. And I was also interested in filmmaking. And I was interested in politics. I worked on Jerry Brown’s 1980 presidential campaign. I went off to Maine and New Hampshire for the primaries. I was 16, 17. I had heard him speak and was very inspired and ran off to volunteer. I don’t mean I ran away; my parents were happy to have me go do that. Even though in general they were pretty strict. We were sleeping on floors, helping to put together house parties where he would meet people, wrangling delegates, setting up phone banks, canvassing, which I still hate. It was exciting. As I recall it, many of the leaders were Cesar Chavez’s guys, organizers. They showed us how to create a large presence with pretty short resources. A few years ago, when I was clearing out my mother’s house after she died, I found a thank you letter from Governor Brown. I kept it, along with a lot of other important memorabilia. For my museum.

So I was always interested in and attracted to a lot of different things and I was reasonably okay at most of them. I still envy people who have one strong direction. I’m definitely a jack-of-all-trades-master-of-none type. And I’ve kind of gone sideways and sideways and sideways, from media to media to media, theater to photography to filmmaking back to theater, to filmmaking again and then drawing and painting, project to project. And in the past that seemed like a flaw or a problem or something that was going to not work well for me, and it hasn’t worked out in terms of being successful or high profile in any way. But looking back and maybe being this age, I’m thinking, I got to learn and do all these different kinds of things, be in all of these different worlds. And I had some great moments, which seems pretty okay now.

I didn’t get to be a go-go dancer—or on a wanted poster. Yet.

Although. Our friend Jodi did pull me aside at a party years ago and ask me if I used to be a stripper. “Because you dance like one” she said. Which was very affirming. Especially at the time. It felt like a lot of my peers were finding their way, having big careers, buying houses and things like that. But Jodi said I danced like a stripper, and she would know, so I felt like I was the winner.

I did get to dance a lot as an actor. I was an actor for over ten years. Mostly all theater. Except for a TV pilot and a couple of commercials. I was a murder suspect on a TV pilot. I was disappointed when I read the script and it turned out that I was just a red herring and not the actual murderer. Anyway, a lot of the shows that I was in, plays I mean—there was choreography, dance, a strong movement element. I would never call myself a dancer by any stretch. I’m not. But I miss that. I don’t miss performing, but I miss rehearsing. Working things out in the room together. I mean, it wasn’t always delightful. It could be wonderful or horrible or excruciating or magical or just tedious. Like anything, I guess. But I miss that kind of collaboration. And I miss choreography. Even though it never came easily to me. At all. When I was trying to learn the choreography for something I would, like, hide behind a column or something because I was always slow to pick it up. And once I figured it out, I would come out from behind the column, and it would okay.

Drumming helped that though. Playing drums between shows, I realized helped me a lot with choreography. I was studying at the Drummers Collective for a while, Cuban and Haitian drumming. And it became easier to pick up combinations, I think because playing drums helped kind of rewire my brain.

For a long time, I thought theatre was the best thing you could possibly do and all I wanted to do, because it seemed to use your whole self, because you’re using your body, you’re using your voice, you’re using your mind, and you’re collaborating with people. So it just seemed like—what else would you want to do? And then I reached a point in my late thirties where I felt like “This is the best thing that one can possibly do, and maybe it’s somebody else’s turn to do it now,” because I was maybe running out of gas. And the collaborative process felt like it was time for me to create my own thing. I didn’t want to direct anything. I had no interest in that, but I had an interest in making things myself.

By that time, digital video had come along, and with short money you could make things. All you needed was tape, if you could invest in a camera and you had a laptop—you could make things. I’ll say that the first stuff that I made was pretty abstract, very influenced by the theater training that I had, I think. Particularly with Anne Bogart’s SITI company, the Viewpoints and Suzuki training, the rigor of that. But I was also trying to figure out something looser, messier maybe. Working out the challenge of how you can make something that feels like a narrative, that has no narrative, but has this feeling, through rhythm and time and juxtaposition, that creates an arc or a sense of story, even though it’s fragments of images, words, overheard conversation. The early things that I did, they were also permeated with the politics of the time. The way politics and personal moments interweave.

Schmidt

There does seem to be, a thread of architecture, politics, economics, personal stories. Everything.

Gagnon

And maybe with this last project, the Island End film, I was able to bring a lot of parts and pieces together. I got to do the research nerding, lots and lots of poring over maps, writing, shooting, sound, editing, the tech stuff, there’s history and politics, some acting in the sense of the voiceover. Voiceover maybe doesn’t seem like acting, but it really is, I think. It doesn’t just naturally come out sounding natural if that makes sense. Editing is my favorite part of the process by far, putting the pieces together, juxtaposing images, sliding sounds and pictures back and forth, making the structure. Creating an overall shape. Rhythm, time. Maybe a little related to drumming?

Island End is kind of a detective story or mystery, though we never actually find the thing that I’m looking for. I don’t find it, but hopefully the investigation or exploration has a strong enough sense of shape or momentum that you’re drawn in and it’s suspenseful. This is a silly comparison, maybe, but I love the Bourne movies, and I think they’re just beautifully edited. I don’t mean to sound pretentious, but if you look at the sequences, if you listen with your eyes closed, there’s this thing that takes you, rhythm. And if you turn the sound off, the color takes you on a ride and it’s happening abstractly. Even though it’s this action movie with lots of plot, it happens on a beautifully constructed abstract level at the same time. I love that.

Screengrabs from Island End

I think Island End came out of couple of things that had bugged me for a long time, that I couldn’t quite figure out—ATM vestibules, push-up bras, shrubs. And financial deregulation. The proliferation of those Wonderbras and Miracle Bras pretty much coincided with ATM vestibules taking over a lot of spaces. And a lot of deregulation was happening at the same time even if we weren’t aware of it. I wasn’t aware of it anyway. Shrubs obviously go back a lot further than that—but there was something about all of them—I mean they all bothered me. The ATM vestibules were these sterile, empty spaces with surveillance cameras. Well, not totally sterile. Some of them were pretty dirty. But I mean they took away social interaction. And they were replacing a lot of my favorite joints and things. And the bras—there was this moment in the ‘90’s where it felt like, “Well if your breasts aren’t this large and this perfect, just don’t even leave the house. We don’t want to see you.” Did you know that when the Wonder Bras first came to New York in 1994, they arrived in a parade of armored cars and limousines? And the shrubs always seemed kind of comical but also sort of like frozen people or something inscrutable like that, something whose real meaning had been lost. And bras and ATMs and shrubs, they shape things in a certain way. Well, bras literally, I guess.

At one point I did some maps of the East Village over time, showing where all my friends lived and where all the ATMs were, and how over time, the number of ATMs grew exponentially, and the number of friends there shrank. The community felt atomized. Everyone was scattered, including myself. I lost my beloved illegal sublet on 11th Street and bounced around for a while. I did a short film about that called Like Home. And anyway, it caused me to start reading a lot about finance. And then the 2008 crash happened, but I was focused on money before the crash. What I hadn’t realized—and what is perhaps common knowledge, but not to me and not to maybe a lot of arts-focused people—is how much the whole financial system is all representation. I had seen it as this very literal thing to do with numbers. Which seemed dull and vaguely bad. But it’s all about words and naming things. It’s all a pile of representations and assumptions. There’s a joke about that. A physicist, a chemist and an economist are stranded on a desert island. A can of soup washes up on the beach. So the physicist says something like “Let’s smash the can open with a rock” And the chemist says “Let’s build a fire and heat the can up until it explodes” And the economist says, “First, let’s assume a can opener.”

You see what I mean? The effects are concrete, but it’s all made of words. And it’s very strange and shocking. I’ve said this before, but it seems striking to me that at a time when there was all of this noise about shocking and transgressive artwork that, under the radar, the really shocking stuff was being created in the financial world—these exotic financial instruments, crazy stuff with credit, all these jaw-dropping dangerous things.

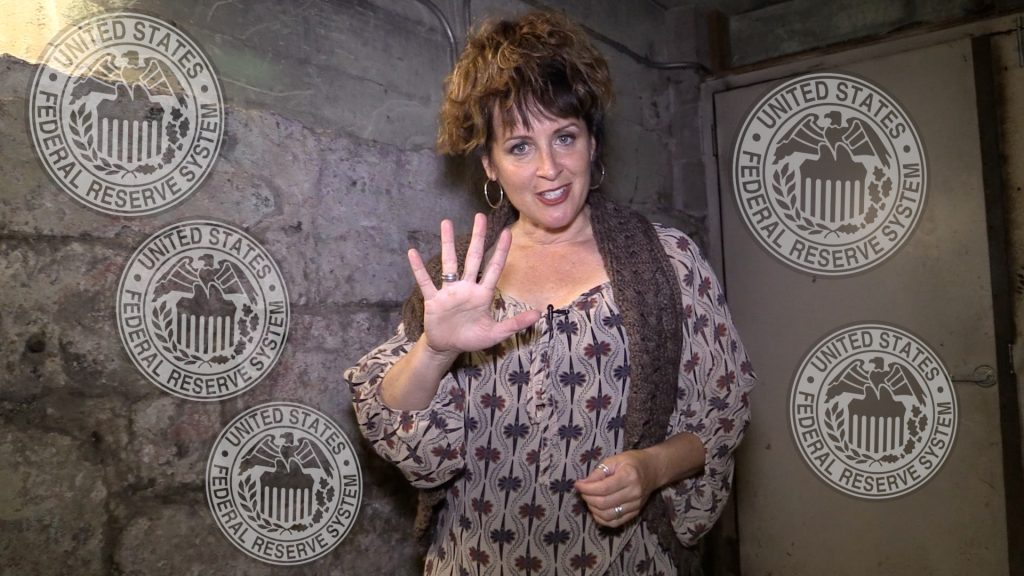

Screengrabs from Like Home.

I tried to figure out how to show this either visually or using a character, because I felt like a lot of people don’t understand that, at least a lot of people I know, and it’s really important. I mean it’s part of why we are where we are today, right? So that’s how I created the Sunny Talks Money character, Sunny Boudreau. I saw her as a YouTube instructor with her own channel. I don’t think it was such a success. I found the financial language and stuff so strange, and Sunny’s a bit strange. In a way they canceled each other out maybe. People liked Sunny. I think because she was funny and earnest—and busty, more so than myself (thanks to a Wonderbra or a Miracle Bra. I forget which, but I got the bra thing in there.) She had a kind of a niche fan club. Of my friends and a few economists. I knew someone who worked for the IMF, someone else whose husband is an economist, a few people in finance. They got the jokes, they appreciated it, but, as a whole, it didn’t quite work the way I wanted it to. It was all one big odd thing, so it didn’t really convey the particular madness of the financial system, the way it’s organized, the weird language.

A lot of times I feel like I’m about 60 or 70 percent smart enough to do what I’m trying to do, and I could use a collaborator to, to sort of complete the circuit.

Eliza Gagnon as Sunny

After the Sunny series, I wanted to do something in my own voice instead of creating a character and I was still thinking about the ATMs, the bras and the shrubs. It seemed like they had something in common somehow—as containers or dispensers or guards? I wasn’t quite sure. But I ended up focusing on the shrubs, which took me along a path to discovering a buried river near where I live and then along a path to discovering a lot of history that had gotten buried there and that’s really buried everywhere. Every place is unique in a sense, but what’s buried under these normalizing things like shrubs and bras and things is this history that we just forget. I mean, again, it leads us to where we are today, the fact of what all of this was built on. If you put shrubs on top of everything, it makes everything seem normal, and it’s not.

Schmidt

I was fascinated by Island End. It starts with the shrubs and the way you talk about the shrubs was so poetic and philosophical and open and beautiful, and then as you move through it, you get to the river and the history and the loss. Where is the river? You can’t find things, and then you go deeper into the history. I think you talked about fires and gas leaks and Phragmites. [laughs]

Gagnon

Yes, phragmites. Invasive plants. I was talking about fires, two catastrophic fires—one was in 1908, one was in 1973—and they started within a few blocks of each other, basically where the river had once been. And it was striking to me that both fires started where there’s supposed to be a river. These fires that burned down huge sections of the city, they started where there should be water. When you bury all of these things, there are consequences. The chickens come home to roost. Can I say that?

But with the shrubs. I was trying to understand them and it was breaking my brain to try to figure it out, their significance. Early on in the process I had a dream about shrubs. I had a dream about a big protest, and in the dream, I was somewhat above, like on a balcony and watching this protest, and it was a pretty serious confrontational situation, and the protest and the demonstration was contained and put down and halted by shrubs, by landscaping. [laughs] I can’t even remember physically how that happened. I tried to figure out how to portray that, and I never did, but it was this idea of this controlling presence. Which sounds silly but it was very serious in the dream. I don’t know. Sometimes I think, is it too dumb? Maybe the shrub thing throws off the balance of the film a little. But you know what? If it does, it does. I took this material as far as I could, and if there’s a slightly better way, then God bless. [laughs]

Schmidt

The way you talked about abstraction and making a story through the abstract. That is the story of the shrubs, from the shrubs you find there’s actually a story of the place and architecture and building and economics and personal stories.

Gagnon

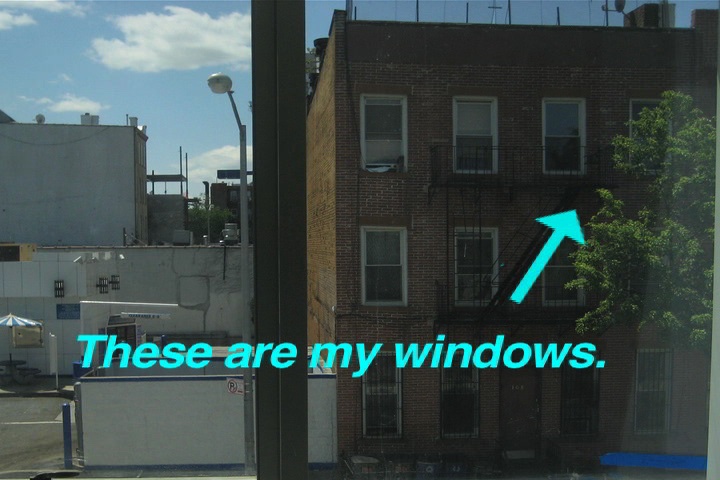

I had been photographing shrubs over time in these commercial areas and noticing what changed around them. Or how they changed. If they did. What I had originally set out to do was to pick one or two sites and try to drill down and see what had been there before because, again, I was interested in portraying the way that credit has changed, the way that laws around credit and finance have changed and how they’ve changed the landscape, how laws have changed the landscape.

I started with this mattress factory that’s close to where we live. It’s this most ordinary cinderblock building that’s been there since maybe 1972. And just to look at this really ordinary spot and see what I could say about that, because I think maybe our problem is that people don’t understand how radically different the economic structure is from what people thought of or believed in in terms of American capitalism. It bears no relation to what it was. Not that it was maybe so fantastic before, but it’s just so different, and I think people don’t have a sense of the scale. Well, maybe they do now, more so.

I picked the little bank site partly because of this older woman I know from the community. I drove around with her one day. She used to work at the huge produce market nearby. All of the produce that comes in and out of New England goes through this area. She worked there and she would bring deposits to this little bank. She said, as we drove by it, “Oh, yeah, I used to bring the deposits there and sometimes the floor was covered with water.” That’s when I realized that the bank is kind of right over the buried river.

Schmidt

One of the things that you go through in the course of this video is that you go back into all the land sales and then the sales of human beings. It was shocking suddenly to see that and understand the importance of American history, of knowing our history, knowing a history that can be seen from looking at one spot.

Gagnon

Right, exactly, and the fact that you could do that anywhere, any one spot and you would see a lot of American history there. You drop a pin anywhere and you’ll find a lot of the same things.

Once I was done with this film, it took so long and was so much harder than I expected, I really didn’t want to look at a computer screen again for a while. Or do long projects, I wanted to do some short silly things. I feel like I’ve kept deferring humor. There’s a few moments of humor in Island End and in some short pieces I made before that. The Sunnys had humor in them. But I think that’s something I want to mix in more than I have, because I think it’s part of how I communicate. But I’m always thinking, “I have to finish this serious thing before I can do my funny thing—”

And I’ve been thinking of resurrecting an old project that isn’t funny at all. The Dust project. About the Big Bang and Original Sin and race and class and war. Hilarious. There was a thing before the Dust project. Projects often come out of failed projects I think, and before the Dust project was a failed project where I was trying to write a script about these two radical women who were part of a bank robbery around 1970, I think it was in Brighton, Mass. A police officer was killed and the women were underground for a long time. One was caught and the other turned herself in years later. Now that I think of it, they might have been on those Wanted posters I was talking about. I did a lot of research, but the more I learned the less interesting they seemed. It started to seem very narrow.

I think the Dust thing partly came out of the idea of wanting to look at something that touched everybody and that anybody could talk about, that was very universal, and also just the idea of why are things the way they are? And if there was no little piece of imperfection, there would be nothing in the universe. It was also about cleaning and class, cleaning and race, religion. It seemed to open the door into a lot of different topics. Because I had a lot of friends who are great talkers and I thought, if I have a topic that anybody can talk about, I can have a myriad of people talking, including a soldier who’d been in Afghanistan and the importance of keeping your weapons clean of dust and the amount of dust over there. And another person talking about how he was trained in the Navy to clean up radioactive waste. A firefighter who was on the pile after 9/11 who spoke about realizing he was breathing in his friends in the dust. It went in so many directions. Our friend Laura talked about cleaning in prison and how she would fantasize about being in her dream house, and she also talked about growing up and cleaning, and the cleanliness of her grandmother’s house and the wonderful smell of it and the associations, positive associations of cleaning. And some people had funny stories. And I also thought the action of it would be interesting to film. It’s sensuous. You’re kind of stroking and caressing your home when you clean. I did an edited version. This was in 2005. I screened it with two other films at the Garden at Sixth and B. And then I had a longer version in a gallery. And then the hard drive it was stored on completely conked out, broke down, and I stopped working on it. It would have taken a lot to reconstruct it. And it was also when I had lost my apartment and was bouncing between sublets. And taking care of my mother, who had cancer at the time. I was back and forth between New York and Massachusetts. On the Fung Wah. So I let it go. But I want to take another look at it. Maybe I’ll do it as a sound piece. I don’t know.

Pretty much though I’ve just been staying off screens and working on some drawing and painting. I’ve actually turned into someone who can draw. But only if I do it pretty much every day. It doesn’t come naturally and if I don’t keep going, I turn back into a person who can’t draw. I forget how to see. But if I do it every day, I get better. Like when my mother was ill, or in any situation where you’re really limited in what you can do, you can always pick up a pencil or pen for a minute. For a while I was just drawing the crumpled napkin on the table after dinner every night and writing the basketball score next to it. So these routines have become important in remembering that steady practices take you places you don’t think you can go. Which should be obvious but it’s taken me a long time to grasp.

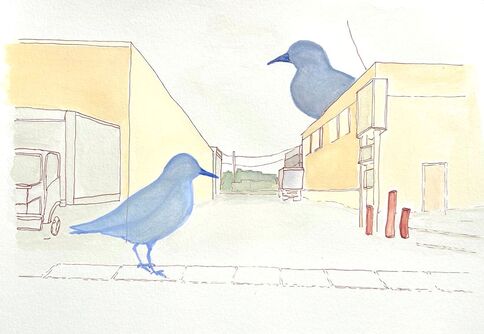

I’ve been doing a painting project that actually is tied into Island End. I started to paint the buildings that are literally sitting where the river was, partly because I wanted to learn perspective. I had the hardest time with perspective, so I thought, “I’ll start drawing and painting buildings. Oh, I’ll do the buildings that sit on top of the river.” And then I started painting these herons. I thought, “This is a very literal idea, but what if I repopulate the paintings with the fauna that would be there if it was still a wetland?” So I started to paint the buildings that are there and then added in these oversized water birds. People liked them and so I’ve been selling them, and then I take the money and I use it to buy food for the local food pantry, because in a sacrifice zone, an environmental sacrifice zone, you’re going to have a lot of other issues, like food insecurity. So the project kind of circled back that way. That’s serious too. I swear once I finish these flood zone bird paintings, I’m going to do silly things. We need some comic relief maybe. Things are so dire but other people are better at addressing these things head on that I am. There’s a lot of great grassroots community organizations here. I’ve joked that they’re all run by very short women in very high heels. [laughs] And it’s true. All these powerful organizations are run by women. Most of them short.

Schmidt

Are you a short woman?

Gagnon

I’ve always considered myself relatively short. I’m not as short as you are. [laughs] I used to think I was 5’3” and then I was told I was 5’4” and then I was told I was 5’3” again. Or 5’2.” But when I was growing up, I was tiny. I was always the smallest person in the class, the one that people would throw around or, you know, if you were doing a pyramid, you’d be, like, on the top of the pyramid.

Schmidt

And have you ever worn high heels?

Gagnon

I have worn high heels. I haven’t much recently, but, yes. [laughs] I’ve always been a little insecure about dressing. I wish I had someone to dress me.

Schmidt

I have nowhere to go after that. [laughter]

LINKS

Website https://www.elizagagnon.com/

Island End https://www.elizagagnon.com/island-end.html

Vimeo https://vimeo.com/elizagagnon

* * *