Can that which is untrue tell us truths relevant to the human condition? How untrue must it/can it be?

Part I: Don Quixote de la Mancha (with a bit of Borges)

As I struggle through the old Spanish of the 1780 version of Don Quixote, I am moved to think of what we, as writers and readers, expect of fiction and its purposes.

¿Significa que Don Quijote de la Mancha es un libro pasadista, que la locura de Alonso Quijano nace de la desesperada nostalgia de un mundo que se fue, de un rechazo visceral de la modernidad y el progreso? Eso sería cierto si el mundo que el Quijote añora y se empeña en resucitar hubiera alguna vez formado parte de la historia. En verdad, sólo existió en la imaginación, en las leyendas y las utopías que fraguaron los seres humanos para huir de algún modo de la inseguridad y el salvajismo en que vivían y para encontrar refugio en una sociedad de orden, de honor, de principios, de justicieros y redentores civiles, que los desagraviara de las violencias y sufrimi-entos que constituían la vida verdadera para los hombres y las mujeres del Medioevo.(Vargas Llosa, X)

Does this mean that Don Quixote de la Mancha is an outdated book, that the craziness of Alonso Quijano is born from a desperate nostalgia for a world that is gone, from a visceral rejection of modernity and progress? This would be certain if the world that Quijote pines for and longs to revive had at one time formed part of history. In truth, it only existed in the imagination, in the legends and utopias that human beings forged to escape some manner of insecurity and savagery in which they lived and for finding refuge in an ordered society, one of honor, principles, apart from civic minded citizens, which made amends for the violence and suffering that constituted real life for the men and women of the Middle Ages.

(trans. Bronwyn Mills)

In last issue’s brief review of two books about the Nakba—the brutal violence against, and expulsion of, Palestinians from their homes in 1948 in what is now Israel—I quoted from Elias Khoury’s Gate of the Sun, which ruffles up the simplistic idea of history vs fiction—“a story is a life that didn’t happen, and a life is a story that didn’t get told.”[1]In my pursuit of the interlocking themes of history, fiction, and the creation of novels and short fiction which include history, I am reminded of the Peruvian writer, Mario Vargas Llosa’s, essay which introduces the 1780, old Spanish edition of Don Quixote. Just to confuse you a bit, Dear Reader, consider that one might amend that Khoury quote to read, “A story is a life that didn’t happen, but looks like it did; a life is a story that didn’t get to be told…”[2]

Indeed, we assume that most of us know our basic history, the stories of how “we” came to be “us”—

“Allons! Enfants du Patrie…”,

“in 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue…”

the Age of Chivalry was a time of courtliness and good manners—

Ah! the Good Old Days! But what Vargas Llosa poses is what if that “history” never was? if it were made up only to give comfort/escape from an insecure and savage reality? Now, the more pedestrian of our fiction writers have struggled to make their work “realistic” and devoid of history or politics, and the “us” has shrunk to the size of a bourgeois nuclear family. At the same time, “history” is not only separated from “fiction,” but at best redecorated as a more amenable, perhaps more well-behaved, even heroic, past, serving not the inspiration of a fictional Quixote, but the ideology of the day. At worst, history is completely absent, if not outright banned. Those who seek to understand the “sins” of the past, aiming to contribute to a more just world, especially in these troubled times, are too often marginalized, censored, and dismissed; for they do not tell the stories the ideologues want to hear.

What Vargas Llosa’s introductory essay in my 1780 Don Quixote points out is the intertwining of these narratives—factual, not so factual but pretending to be, and flat out fiction (“once upon a time….”) Further, Don Quixote itself is often cited as the—THE—Ur-text for for the modern novel.[3] Some have gone on to tie Cervantes’ work to the so-called ‘magical realism’ of Latin American literature: that being unlike too many novels in the more northerly tradition, in the stranglehold of’ ‘social realism’, which rest on the assumption that the fantastic and fabulist are only for children. Mind, Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle was a noble protest against real social abuse. Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man directly attacked the US’s endemic racism. Albeit Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath had a noble purpose, in no uncertain terms siding with the sufferings of the working man, the dispossessed, etc. as Steinbeck did with those in Cannery Row, and the Mexican-American paisanos in Tortilla Flat, a book subsequently under scrutiny for possibly succumbing to negative stereotypes. In terms of social protest in Anglophone literature, science fiction bridged the gap for a while —1984, Animal Farm, Invisible Man, The Handmaid’s Tale—but we are now in a semi-literate age and within a polity who rarely read books and with less and less concern for the working stiff or other ordinary citizenry. Whatever his illusions were about a noble past age, Don Quixote, as Vargas Llosa points out, does try to help his fellow human beings, believing that as shown in the invented chivalric past, it is incumbent upon him to do so.[4]

Indeed, rather than simply writing a fiction that strives to reproduce everyday reality, Varga Llosa’s essay emphasizes,

Así nos enteremos de que existe otra realidad, otros tiempos, ajenos al novelesco, al de la ficción, en los que el Quijote y Sancho Panza existen como personajes de un libro, en lectores que están, algunos dentro, y otros, «fuera» de la historia, como es el caso de nosotros, los lectores de la actualidad. Esta pequeña estratagema, en la que hay que ver algo mucho más audaz que un simple juego de ilusionismo literario, tiene consecuencias trascendentales para la estructura novelesca.

(Vargas Llosa, XXIII)

...we find out that there exists another reality, other times, alien to the novel and to fiction, in which Quixote and Sancho Panza exist as characters in a book, in readers that are sometimes within, and others outside, history, as is the case with us as contemporary readers. This small strategy, in which we must see something much more audacious than a simple game of literary illusion, has transcendental consequences for novelistic structure.

(trans. Bronwyn Mills)

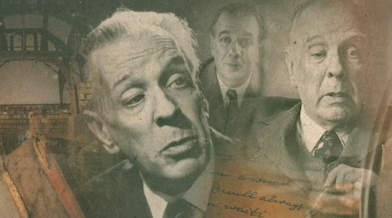

“Oh, Magical Realism!” Fiction that is too fictional (fantastic?) is for children! Once more, in terms of the much misunderstood labeling of subsequent work inspired by Cervantes, that of “magico-realismo,” Vargas Llosa more specifically comments that Don Quixote‘s world is ‘Borgian’, I thus must turn to Jorge Luis Borges. Vargas Llosa proposes that the world of Don Quixote could be seen as like what Jorge Luis Borges’ “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” does— for those who have not read Borges, as a Cervantian theme resuscitated by Borges in that work. Borges begins innocently enough, referring to having dinner with Bioy Cesares (a very much real person, writer, and sometime collaborator of Borges) and a conversation at that meal in which Bioy is credited with starting the search for, “…a scheme for writing a novel in the first person, using a narrator who omitted or corrupted what happened and who ran into various contradictions, so only a handful of readers…would be able to decipher the horrible or banal reality behind the novel.”[5] That may be a question particular to Bioy Cesares, but he and the narrator (Borges) both allude to Uqbar and the heresiarch from Uqbar who referred to mirrors and copulation as “abominable” because they multiplied, resp., images and seres humanos, human beings. Borges’ tale unfolds as the two writers (and others, also quite real, of Borges acquaintances)—as they search for this fictional, variously asserted to be real—place, appearing and finally disappearing in copies the Anglo American Cyclopedia.[6]

Borges’ tale continues with a dazzling mix of the personal and the fantastic, the fictional Uqbar and other connected (fictional) places. As narrator, he happens upon A First Encyclopedia of Tlön and, prominent on its title page, “ORBIS TERTIUS.” There, Borges claims, he found “a substantial fragment of the complete history of an unknown planet…” (21) Oddly, these Borgian places do seem a bit more fantastic than the invented world of chivalry which Don Quixote looks back upon with yearning. However, here we also have here the beginnings of a an inventive meander into how to consider writing/inventing a fictional world and one which, in a mix of the fantastical and a mundane reality, is illustrated by the twists and turns of the story’s shape-shifting narrative itself. Ah, Borges!

On the other hand, I wonder if Vargas Llosa, Cervantes and Borges (oh, and while we’re at it, Bioy Cesares) would genuinely agree on the nature (and purpose) of fiction and, for lack of a better word, ‘reality’ combined in novelistic form. Borges, who learned from his grandmother to read English before Spanish—Borges was a great fan of Robert Louis Stevenson, de Quincey, Edgar Allen Poe, though his erudition did not stop there. He also added Kafka, not exactly an Anglophone author. Nor do we necessarily think of all those (Kafka, perhaps) as inspiring the fantastic in adult literature. Cervantes himself lived anything but a quiet life, and freely engaged in invention and satire through his aging knight, Don Quixote, as well as in other work. Yes, he was an inspiration to many; and Cervantes is certainly listed as one of Borges’ revered writers. Yet, like any genuinely creative artist, Borges was not a copyist, but one who allowed others’ work to set his imagination alight, allowing it to wander off in a unique direction. Nonetheless, should you, dear Reader, care to look at Borges Ficciones, in which “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” appears (Ficciones‘ Part One, The Garden of Forking Paths) you will quickly see that the intertwining of reality, fiction, and the fantastic take their own path in several other of those tales as well.

Finally, the point Vargas Llosa makes about several realities is well-taken; and he may very well have a good case for ascribing to Don Quixote and others’ work the title of his 2004 essay introducing the 1780 version of Don Quixote—”Una novel para el siglo XXI” (“A Novel for the 21st Century.“)

— Bronwyn Mills

In the US, see Bookshop.org for Borges’ Ficciones, in the UK from World of Books in English and Spanish.

NOTE BENE: Varga Llosa recently passed away at the age of 89. For a more fulsome report on his passing please see The Guardian, April 25. 2025.

* * *

[1]Omar Khalifa’s Sand-Catcher, in that review, deals with the latter, the story untold.

[2] Reminiscent of the mum grandfather in the Sand-Catcher, the other book reviewed in the review of those two Nakba-themed ones in our Issue 8, Remarkable Reads section. (Nakba, in Arabic, means ‘catastrophe’.)

[3] See William Eggington’s The Man Who Invented Fiction (Bloomsbuty, 2016). An interview of Eddington in Johns Hopkins magazine also goes into his ideas further.

[4] Mind, Vargas Llosa himself, from his youthful concerns, lurched to the right, and held political views which, to many of us, are reprehensible (see The New Yorker, JY 10, 2023.)

[5] Jorge Luis Borges, “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius“, trans. Alistair Reed, in Ficciones, Grove, 1962. p.17

[6] Which Borges cites as published in New York (1917). Google cites this as “a literal (but delayed and pirated) reprint of the 1902 edition of the Encyclopaedia Brittanica.” (accessed 18/4/25) and, to quote from the University of Pittsburgh Borges Center, “In private conversation with the present writers, Borges maintained that he owned a copy of the untraceable ‘cyclopaedia’: this may be an oblique reference to the Eleventh Edition, which he certainly owned.” (12) See https://www.borges.pitt.edu/i/anglo-american-cyclopaedia.