The Cure for Convention

There is no cure?

The cure is the cry of pain?

The cry of pain is the radio?

The pain of the radio in the car is the cure?

The pain of the cure is the cure?

—Richard Foreman, The Cure (1986)

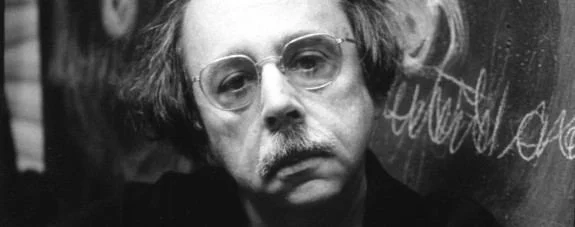

When the award-winning playwright and director Richard Foreman died on January 4, 2025, he left a legacy of 51 plays, nine opera libretti, eight films, and 14 books of essays, scripts, and musings. A prodigious output indeed, for an artist who napped during the day to clear his mind and begin anew. As he wrote in one of his essays, “I SLEEP. I NEGATE THE DRIFT of the writing burst I’ve just fired…I wake up cleansed and fire again.”

A nap cured Foreman of what he dreaded most: conventional writing that flows into a continuous “river of discourse” or gives an audience some message or emotion to carry home like “baggage” from a night in the theater. The cure of sleep, implying an awakening to start creating again, signifies the lifeways of Foreman’s New York in the 1970s and 1980s. This gritty and romantic time was Foreman’s crucible, even though he worked well into the 21st century, One way to unpack the writer’s work is to consider three verbs—sleep, cure, start again—in a city that was financially bankrupt in 1975, yet rich beyond measure in art. President Gerald Ford may have told the city, per the famous Daily News Headline, to “drop dead.” But New York people who made art, like Foreman, were rising from curative naps to release fresh and unconventional work.

Foreman hit his stride as a playwright around the same time as The Wooster Group, The Poetry Project, Andy Warhol, the Minimalists, and Patti Smith were hitting theirs. Foreman was reacting against slightly earlier experimental work like Jerzy Grotowski’s immersive and stripped-down Poor Theater. In his Ontological-Hysteric Theater, Foreman reached for what the poet Charles Bernstein has called “polyphonic elaboration”—an experience of speech, music, sound effects, and the odd rustle of Foreman’s unusual props, decorations, sets, and costumery. Evocative, nonlinear speech mixes with the sound of jazz clarinets, and the clank, rustle, or squeak of television sets, chains, taffeta, and hobby horses. Personae act impulsively, with the playwright “reveling in characters who act in self-contradictory ways and plays which constantlt get knocked off track,” in the words of critic Raphael Rubinstein.

Lava (1989) written and staged by Foreman.

The embellished polyphony of Foreman’s plays reflects the process of sleeping, cure, and starting again. Eric Bogosian, who interviewed Foreman in 1994, called Foreman’s plays jarring and aggressive, frenzied and funny. Foreman suggested during this interview that the character of his work…

“…lies in that step-by-step playfulness with all the ideas that are in the air, all the references, all the allusions. To me, that is the potential delight of art, and all other meanings that can be abstracted are forced because any conceivable meaning is qualified by some other meaning that somebody proposes. I am not interested in making plays that say, Here is the message. I am interested in plays that put into play in exhilarating fashion, all of the different meanings circulating around us.”

When Foreman wrote, he pulled circulating meanings onto the page. If the urge to create a conventional flow or message arose, and he slept to cure this urge. Foreman woke, and began afresh, back to the exhilarating grab for ideas. The scholar and artist Kate Davy saw Foreman’s process as akin to that of Gertrude Stein, the artist who Foreman maintained was the primary influence on his writing.

Davy considered Stein’s “entity writing”—organic, immediate, discontinuous, and intimate, without a sense of audience—the template for Foreman’s plays. The process of the artist is essential to produce entity-writing; when the writer opens up to receive the present moment as it actually is, the writing will have immediacy, intimacy, and the discontinuous riot of true experience. Stein believed that “beginning again and again” was the way to make this process happen. Foreman seems to have taken this to heart, napping, waking a starting afresh to cure the continuity, time-frames, and service to audience that Stein called “identity writing” and that Foreman despised.

Given this connection, it make sense that Foreman’s scripts often feel like deconstructed prose poems, rather in the spirit of Tender Buttons, as in Ben’s lines from Hotel China (1971)

Eating dinner.

If I…

Lived here. A: You don’t live here, Ben. B: You still do things even though you don’t live here. Different people would have different problems eating dinner. —What— Rhoda would have something covering her face and the food couldn’t get into her mouth.

Karl would have a different problem.

All of us would have the problem of not sitting at the table and being on the floor lying down

If the table was sideways.

To sleep, to cure convention, to begin anew—Foreman’s approach feels like the gestalt of New York in the 1970s and 80s. A nap and a creative clean slate, abetted by a wild city with no computers, no smartphones, no “always on” work culture. Artists may not all have napped intentionally and for Steinesque purposes, as Foreman did. But the art of the time evokes “beginning and beginning again” everywhere, all the time.

The evocation is there in Patti Smith’s line from M Train, “Nothing can be truly replicated. Not a love, not a jewel, not a single line.” It’s there in Alice Notley’s “Poem,” that opens with “St. Mark’s Place caught at night in hot summer,” then contradicts itself in the erasure of St. Mark’s Place, “this night never having been.” Richard Foreman distilled it, wrote it, and put it on stage—his experiment of an immediate, new-created art, fresh from the naps we don’t take much these days.

Scene from King Cowboy Rufus Rules the Universe (2004), written and directed by Foreman; photographed by T. Ryder Smith at St. Mark’s Church—for more photos, click here.

Author’s note: click on each name, to read the essays and interviews by Charles Bernstein, Eric Bogosian, Kate Davy, and Raphael Rubinstein discussed above. Rubinstein also has writing in this issue of Cable Street—click here.

—Dana Delibovi

***