Lyric Chapbooks from Three of Cable Street’s Past Contributors:

Elissa Favero, Diane Alters, and Kelly Egan

Children of Rivers and Trees by Elissa Favero

Elissa Favero’s elegant new abecedarian of lyric essays, Children of Rivers and Trees, bears a title that captures its contents perfectly. The essays weave together the threads of family and the natural world, to create a polychromatic fabric of rich texture. From the opening essay “A is for Ancestral Plant” to the closing “Z is for Zigzag,” Favero wrapped me in a supple cloth of heredity, environment, history, and the sacred, and I felt warmed and delighted.

Favero is a descendent of Scottish and Italian forbears, spread from Maryland to Montana, Washington DC to Washington State. The author’s lineage suits the abecedarian structure, which mirrors the many intricacies of blood, marriage, and affection from A to Z. The essay “Family” plays with the linearity of biological classification, rising through species, genus, family, class, phylum, and kingdom to create a descriptive order within the book’s alphabetical order. Then, Favero shows us how the order of human relationships makes room for unexpected connections:

I grew up in a nuclear family, that ideal of American life in the middle years of the twentieth century. As an adult, I’ve broadened my definition of the word family: any group forming a household. No bloodlines or genealogical trees necessary. Few legal ties.

For a season, I share my life with others under a leaky roof as Seattle’s spring rains run as atmospheric rivers above us.

The contrast between straight-line order and natural deviation forms the core of Favero’s book. It is the creative rationale for the abecedarian structure. Beneath the surface rigidity of alphabetical order, curl the tendrils of familial love and wild nature, and the way a firm trellis holds a twisting vine. The contrast between fabricated order and natural salmagundi also builds the rich emotional tones of the book. As human beings, our organic selves press against our constructs of language, logic, and civilization, causing anger, frustration, and sadness, but also feelings of hope and resolve.

One example of this is the essay, “M is for Maiden.” Here, the traditional social organization of women’s maiden and married surnames, which obscures the true, consanguineous, self, triggers a cascade of emotions. Just as the young “maiden tree” in horticulture take on its shape through “husbandry,” so too does a woman’s life—and both hide their wild nature under what has been forced upon them:

When my own great-grandmother wed in Pocatello, Idaho, in 1912, she left behind Muir, the name she shared with the famous Scottish-American naturalist, to take Scotty’s name, Marshall. My grandmother, in turn, gave up Marshall when she first married. She took my grandfather’s Italian last name, Favero, in its place. And my own mother made her Polish maiden name, Jakusz, into a middle name to adopt my father’s name, Favero, as her surname. A series of effacements; an accretion of names.

They and the many, many who came before course beneath my skin as bloodlines, a near infinite system of inherited roots that form the flowering tree of my bending, listening, registering, thinking, turning body. They are all there, obscured by time passed, concealed beneath my maiden name.

As is apparent in this passage, Favero’s prose style is graceful and evocative. The brief lyric essay challenges the best of writers, but the genre flows effortlessly in Children of Rivers and Trees. Prose and prose-poetry merge in this book, allowing the author to link botanical, geologic, and human-social imagery in ways that would be denied to a traditional essayist. While reading, I was often reminded of the fluidity of Byobu, the abecedarian written by the great Uruguayan poet, Ida Vitale.

I cannot give Favero’s book a greater compliment than this: she is an heir to Vitale in her lyric prose and her ability to connect images and concepts seamlessly and without a moment of strain. Children of Rivers and Trees is a gorgeous and resonant book. It elicits the full range of feelings that arise as our natural, authentic selves chafe against the rational, linguistic order we impose.

Elissa Favero’s contributions to Cable Street can be found here and here.

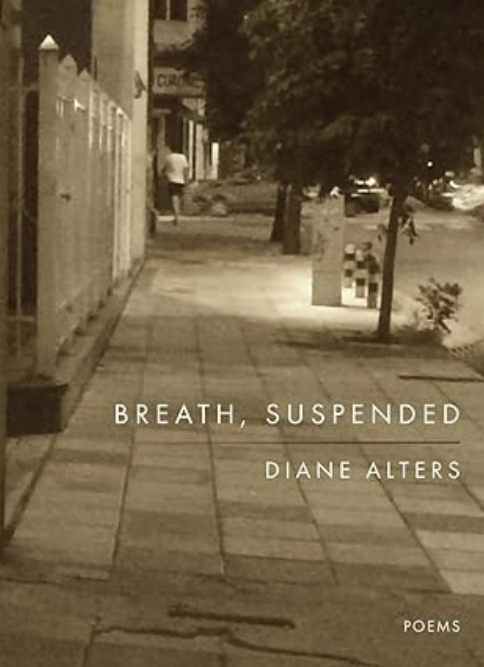

Breath, Suspended by Diane Alters

The poetry in Diane Alters’ Breath, Suspended arose from the crucible of grief. The book is a memorial to her son, Mando, a promising journalist who died at age 22 while on assignment in Mexico. Every poem in the collection pulses with the unbearable loss of a child. Each poem compels us to face the deaths we fear the most. Each shines a brilliant light where we dare not look.

In the manner of all fine elegiac work, Breath, Suspended captures the shock and gravity of death, yet brims with love. The opening section of the book “All That Is Solid Melts,” opens with a poem that manifests the book’s title. “Into Thick Air” literally stops the breath, the initial blow when Alters learns of Mando’s death, follow by the choking realization that her beloved child is gone. Any parent —indeed anyone who loves another dearly—will experience the physical suffocation of a day we all dread:

Hours later, word

of what happened

jackknifes my body

belly burning

breath stolen

light scattered—

All that is solid

melts

into a hole

in the air.

As these stanzas show, Alters possesses a very keen metric and musical ear. She writes free verse, but the rhythm and tonality of her poems owes a debt to the formal poetry of our language. The allusion to classical English poetry gives her work both dignity and solemnity. These qualities prevent the poet’s strong emotions from descending in bathos and infuse even simple lines with an oceanic or spiritual mood. The result are elegies and remembrances in which the poet’s personal experience connects with what is universal.

As case in point is her short poem “Five months before Mando died.” At that time, Alters and her husband Mario talk about Trayvon Martin, the young man murdered while walking home by the racist, zealous vigilante, George Zimmerman. “This could happen to Mando, / Mario said.” Later, after Mando’s death, husband and wife watch a clip of Trayvon Martin’s parents “on a hotel television / as we travel / in a grief stupor.” The formality of theses line—in the first phrase, for example, trochees bookend a dactyl—elevate the simple words and images. We all travel with Alters, we feel her stupefying grief, we recall the losses we have endured.

Although Alters’ poems mourn, they are also alive with sensation, emotion, and acceptance. Not one word in the text occasions pity for the poet, her husband, or her child. Alters never asks us to feel sorry for her. Rather, she asks us to share her experience, to know the depth of her sadness but also the permanence of her love. The book’s third section, “Memory, Aspirated” gathers into six poems image after image of survival—Alters survival through grief, Mando’s survival in objects and events.

A family comes searching for Mando’s bone marrow for a transplant, because in life he had made himself available as a donor. Mando’s name comes up, with explosive force, as Alters and friends paint a house. In “Lost,” the poet loses a colorful scarf that Mando had said lit up her eyes, and it triggers a crystalline moment of surrender:

I thought

when I lost him

I would never

mourn

another loss.

All would pale.

But absence

lingers

in its own space

clings

to my neck.

To this

I acquiesce.

Reading Breath, Suspended was a fraught experience for me, the parent of two young men. Poem by poem, I felt a chill up and down my spine, as my empathy for Alters brought up all the terrors I have about the safety of my sons. Children can pass before parents. People sometimes call this “unnatural,” but it’s not, and using that word is profoundly cruel and shaming to anyone whose child has died. There is no law of nature that says a child must outlive parents, even though we wish this were so. Alters gives comfort to grieving parents, by showing that a child’s death is natural part of life’s risk—in her case, her son was a journalist, and chose to face a “hand grenade here” or “a bomb at Atocha station.” But the poet also demands that the rest of us confront the deaths we cannot bear to imagine. That demand is the singular power of this remarkable book.

Diane Alters’ contributions to Cable Street can be found here.

You can also listen to Alters in conversation with

Edward M. Hirsch, a contributor to this issue, and Elizabeth Howard

on poetry and the loss of a child, here on The Short Fuse podcast.

Millennial by Kelly Egan

The poet Kelly Egan knows her way around a line—especially a first line. She tantalizes, shocks, and ropes me in with her poetic openings. Once there, I stay for Egan’s feast of words and images. Egan is a modern, secular version of my own poetic icon, Teresa of Ávila, because both trade in surprises. Several commentators have remarked that, in reading Teresa, they are often seized with the thought: “Did she really say that?” The same occurs when reading Egan—startled, astounded, and finally hooked.

In Millennial, Egan’s chapbook of 21 numbered poems, the poet does the unexpected every chance she gets. It’s awild ride, running roughshod over the spatiotemporal constraints of poetry.

Throughout the book, historical events, oddities of the present, and imagined futures merge with the poet’s childhood and adulthood, creating a place “not ruled by linear time, though it is not altogether unruly.” The verses leap across space and points of reference—as in poem 8, which jumps from the history of witchcraft to a cabin in Palm Springs. Some poems are contained at the left margin, some spread their limbs wide across the page. The book is a musical cacophony, in service of one profoundly perceptive idea: the Millennial generation grew up with noise, fragmentation, and the hyper-drive of parental expectations, and they are determined to make meaning from the mix. This idea appears—poetic imagery as thesis—in the opening poem:

Running on this grass, never not a soccer game

Whiff of pineapple

White space

Italian ice?

Giving myself away from this place

childhood home

*

Removed my IUD

which made things go back to normal

down there & then I wanted to travel

For Millennials, running on grass meant playing a parent-organized sport from kindergarten through high school, and even into college; Egan’s zinger of a first line captures the whole stressful mess in nine plain words. Pleasure arrived in bits—a scent here, a taste there, maybe a break to experience nothing (white space) instead of the relentless next activity or next screen. Technology, like the medical technology of the IUD, causes harm, getting away from it normalizes life and permits the desire for experiences, like travel. Egan “gives” herself away rather than “goes” away from her Millennial childhood. She offers all of her feelings and events of this childhood to the page, so that readers can find their value.

As the book progresses, Egan digs deeper into these themes with the shovel she wields so well: the image. Egan is in many way heir to the American imagism of H.D., Amy Lowell, and William Carlos Williams. The image does the work and there is no need to philosophize. The images in poem 14 fuse together two Millennial experiences, the rise of the smartphone and the ruin of the environment:

The basic building block

of my life: my room.

My room the infinite where a phone

crushes me…

The coyotes came down from the hills

into the empty city

She follows up with poem 15, a devastating 4-line imagist poem that continues to explore the “hills” image of part 14, and ends: “A power station rendering/a hill invisible.”

Imagism, as is well known, is a particularly painstaking craft, yet Egan’s poems never seem strained. The sound I hear is never the huff and puff of effort. It is the concerto of a musician who likes to switch to dissonance just when I expected harmony. Egan employs many elements that can make a description into an image, that is an amalgam of sensory portrait with thought and emotion. These elements include alliteration, assonance, and vivid diction. But these features are woven with subtlety into Egan’s poetry. The experience of reading is always natural, even if Egan makes sure to stun us now and then.

What is the meaning Egan finds in the Millennial experience? To answer the question fully seems like a spoiler. But I can suggest that Egan knits the Millennial jumble—from tech to terror—into the comforting blanket of human intimacy. Beyond the phones and the pressure to perform is the desire “to feel alive,” to speak kindly in a society where “comfort is the word no one is saying.” Schooled by the Millennial experience, Egan insists on being a flesh and blood human, a lover of life, even as she is a witness to the devastation of every living thing caused by human folly. And in this, she is wise beyond her years.

Kelly Egan’s contributions to Cable Street can be found here.

* * *